In certain parts of the country, it’s a well-worn joke that you can be longtime neighbors with someone and never know each other’s names. But in recent times, the polite distance between many of us has closed — even if, thanks to the pandemic, we’ve never been more physically far apart. We’re beginning to recognize just how important our support systems are to keeping us healthy and safe.

Counting on others applies to how we make change happen, too. We’ve witnessed the power of on-the-ground organizing in the past, but seldom with this emotional ferocity and perhaps never before in a period that has so tellingly exposed the limits of the institutions we believed we could rely on. We’ve seen what listening, coming together, and pitching in can do, and we’ve only just begun.

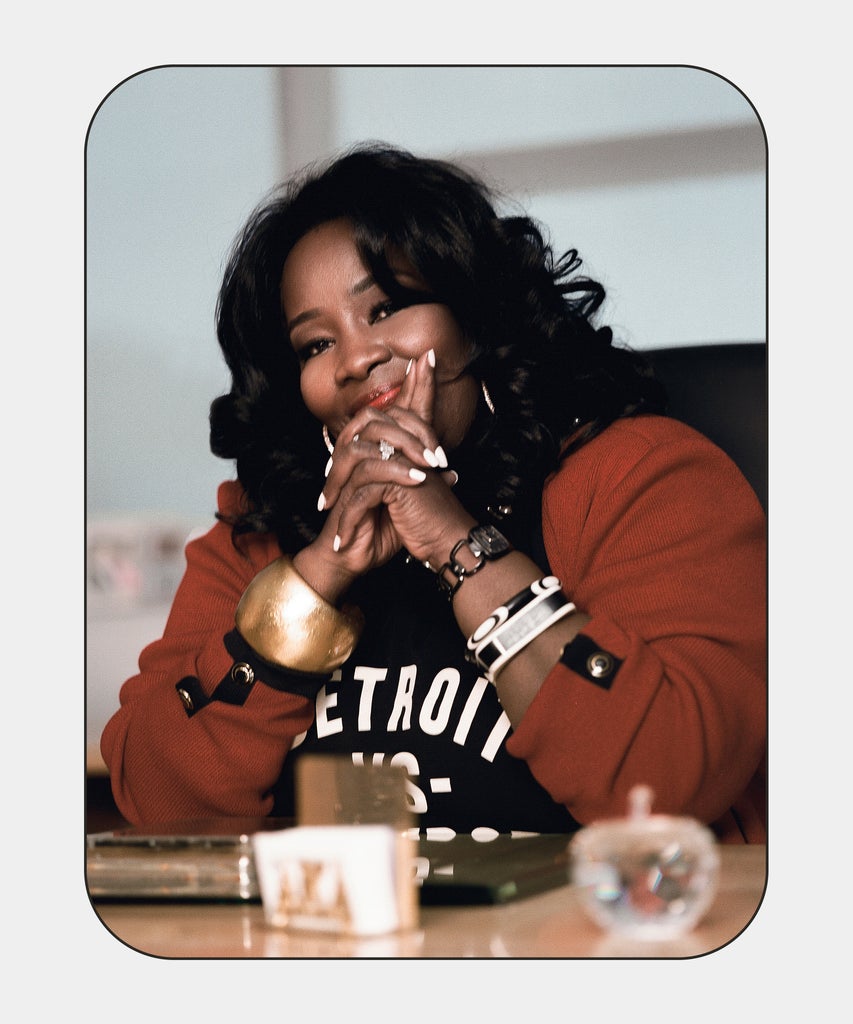

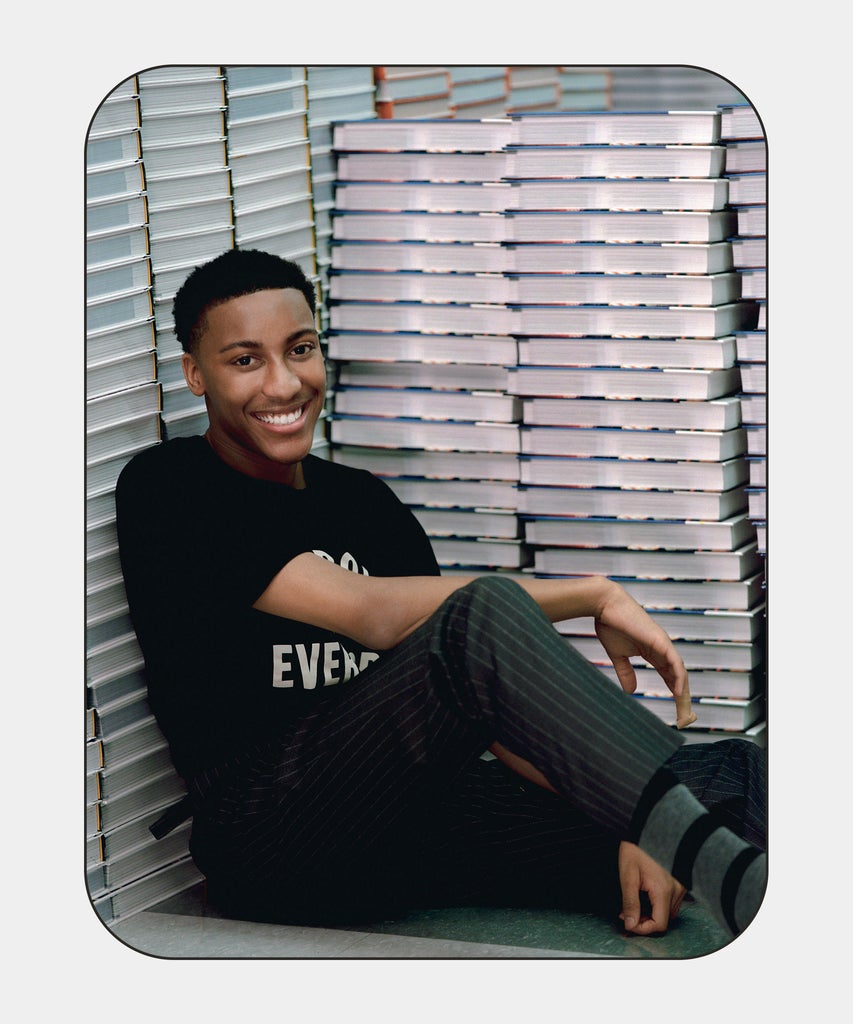

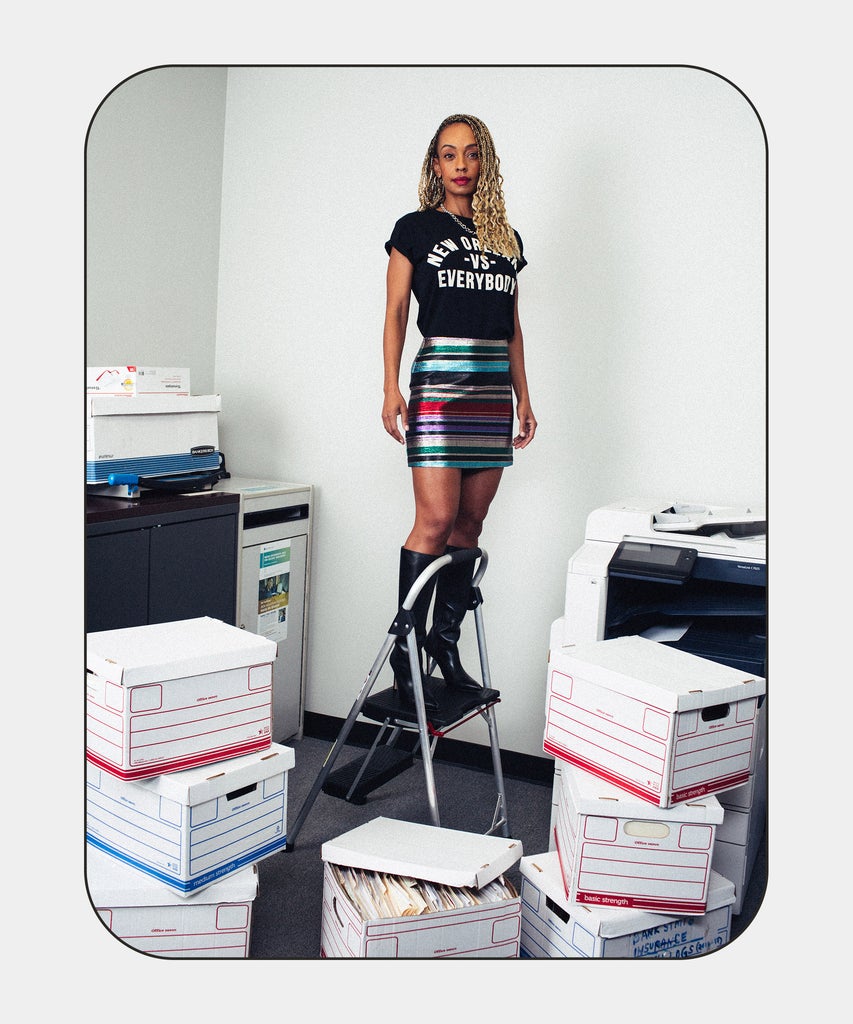

To accelerate and sustain positive social change across America, the Gucci Changemakers program provides donations to community-based organizations in 11 U.S. cities, three of which we’ve recognized here. Ahead, meet the leaders of these groups — pictured wearing GUCCI VS. EVERYBODY, a collaboration with designer and Changemaker Tommey Walker of DETROIT VS. EVERYBODY — and find out how their work has directly improved the lives of an expanding circle of families, friends, colleagues, and beyond. Because when one person acts as a change-maker, it sets off a chain reaction; and when we empower those around us, all of us rise.

For many at Custom Collaborative, a New York City-based nonprofit that helps women from low-income and immigrant communities launch careers in fashion, lockdown has meant learning a new skill set digitally for 30 hours a week with other program participants spread across more than 20 countries. And yet, according to executive director Ngozi Okaro, even amidst the cultural differences and so much pandemic-related loss, program participants have also found it within themselves to make and donate masks, find their classmates housing, and offer guidance to one another with honesty and generosity.

“The stories they share are so much more meaningful than anything I could say because it’s peer-to-peer,” Okaro says. “In one of our Tuesday makers’ meetings, someone said, ‘I want to be rich’ and then quickly followed up with, ‘And I want all of us to be rich. I want all my soul sisters to be rich.’ It’s this collective spirit that excites me and makes me feel like there’s not one person who makes this thing go. It’s everybody’s collective energy that’s creating opportunity for the rest of us.”

“When I came [to Custom Collaborative], I was making clothes for my church members, and they were paying me peanuts. I didn’t know I was being used. Custom Collaborative helped me learn to charge what my time is worth. It was something Ngozi and the group were always, always telling me, like, ‘No, you don’t have to be scared [of raising your prices]. You made this clothing with love, time, and your sweat.’ She’s inspired me to create a Custom Collaborative in Nigeria. I think about what she’s done and what I can take back home because she has inspired me to be a better person.”

Ifunanya Onyekwere

Custom Collaborative graduate and owner of Aifys Clothing

On her end, Okaro has set up an organization that’s agile and “trusted in the community, because we’ve built ourselves from the ground up with their input.” This means surveying the population and moving quickly to respond to needs like food insecurity, a model Okaro says she would like to eventually scale to as many as 10 cities domestically. Her plan for the near future also includes establishing a flagship in Manhattan’s Garment District to act as an all-in-one learning center (complete with drop-in childcare) and a hub for small and emerging designers, but Okaro says she’s ultimately building with the intention of one day rendering her own creation obsolete.

“The final iteration of Custom Collaborative would be when the industry has transformed in a way that pays people fairly, doesn’t pollute the earth, and provides people with clothes that make them feel good about themselves. And so when we’ve done all that, I’ll check off the box that we can close Custom Collaborative.”

“Custom Collaborative has been my angel. When I started learning, my husband was infected with COVID. He was in the hospital for eight months. Custom Collaborative was the first responder for me. They gave me a lot of support and established a balance in my life during such a hard time.”

Isabel Espinoza

Custom Collaborative graduate

Detroit’s Cass Tech is the largest high school in the city, with 2,479 students, a 99% percent graduation rate, celebrity alumni, and a 100-year legacy that Lisa Phillips, its principal of 11 years, says she refuses to rest on.

Instead, Phillips has made pivotal changes, like implementing a med-school-track program that has ninth graders shadowing surgeons in the operating theater and a philanthropy-driven curriculum that saw students driving in a caravan to deliver water to Flint. But beyond ensuring that her students are exposed to different career paths (while caring for others along the way), Phillips has introduced a culture of radical openness in an educational structure that has traditionally flowed only from the top down. In these halls, impact moves in all directions.

“Principal Phillips approaches her work as a mother,” says senior Lamont Satchel, Jr. “It’s not all pomp and pageantry; it’s ‘If you need to talk, let’s go.’ It’s that ability to be fluid with your title so every person from student to faculty to custodian can confide in her.”

“Mrs. Phillips and I have been tag-teaming since 1998. When I came to Cass, I remember her saying, ‘When you get in there, throw down.’ Those were her exact words. I’m like her mini-me. She’s impacted the type of counselor I am, and I consider her a role model and mentor.”

Monica Jones

Cass Tech counselor

Satchel, whom Phillips in turn calls “a voice of resolve,” knows this firsthand. As a student leader who often acts as a bridge between the adults and students at Cass, he’s a member of Phillips’ Focus Group initiative, in which representatives from each class bring an on-going issue to an open forum attended by faculty and students. In one recent meeting, the representatives ended up shifting Phillips’ attention from test scores to her high-schoolers’ mental wellbeing — and strengthened her conviction to always hear them out.

“You can’t say, ‘Let’s listen to the young people, but we make our own decisions,’” Phillips says. “They have to play a major role in our community. In a lot of decisions that are made on a local or national level, they’ll have maybe one kid to represent all of them — no, it has to be systemic.”

By practicing direct communication and encouraging her students to use their voices to uplift others, Phillips is helping to raise a generation of dreamers and doers like Satchel Jr.

“My biggest takeaway from working with Lamont [Satchel Jr.] is we need to show up for one another. We need a diverse coalition of seats at the table. Whatever he’s working on, Lamont does a good job of making sure he understands the perspectives of different people.”

Mohammad Muntakim

Cass Tech senior

“When we talk about social impact, we talk about accountability,” Satchel Jr. says. “But I think the first thing is understanding the meaning of community. It extends beyond a ZIP code or the color of your skin. In my activism, what keeps us moving is hope. We’re being the change-makers. So knowing that there are people out there with hope, courage, and love inspires me and Principal Phillips. So listen and invest in us. That won’t just make life better for my generation — it’ll make life better for all.”

What many of us will remember about the summer of 2020 is the vital pull that kept calling us back to march, night after tense night. But now that those same streets ring less loudly with cries for racial equality, we might find ourselves wondering: Even when so much else demands our attention — even when so much else has happened in the meantime — how do you maintain momentum?

For Alanah Odoms, executive director of the ACLU of Louisiana in New Orleans, the fight to end mass incarceration, educate voters, protect reproductive freedom, and above all, defend “the right to live and breathe without being targeted” is powered by the people — including those whose experiences don’t make headlines.

“What we’re doing is hearing the stories of brutality and abuse, filing cases, and creating a repository of community narratives, not just in Louisiana but across the country,” Odom says of Justice Lab, the ACLU’s police accountability project. “To address many of these issues, the first thing I did when I came to the ACLU was sit down with members of the activist community and think about how we take grassroots activism and bring that power to the statehouse and the courts.”

But what can the average person do to propel these causes forward? The answer, according to development director Maggy Baccinelli, lies with listening, “building your foundation of understanding” by reading and studying, and advancing — through volunteering and donating — the work of “Black and Brown people who know firsthand the perils of structural racism and are uniquely qualified to address it.”

Only through allyship and widespread cooperation can we remake the world — one in which everyone is treated with dignity and fairness. To Baccinelli, getting there looks like inventing a “first-of-its-kind model for connecting supporters and major donors to the reparations movement.” And for Odoms, it’s “a dramatic and radical re-imagination of our criminal-legal system” as a means to “get to the heart of a lot of other, more pressing social issues of our time involving race.” But none of this will be possible unless we put our malaise aside and keep going.

“I can relate to feeling like the problems are insurmountable,” Odoms says. “But the moment we’re in is only matched in significance by the civil rights movement in the 1960s and Reconstruction. So history has its eyes on us right now. I really do believe that each of us have a power to contribute to this greater movement for equality and freedom. We don’t have to have formalized degrees to do it. We don’t have to be bona fide community activists. But we do have to use our spheres of influence as best we can to catalyze change.”

“With Alanah and Maggy allowing me to do a virtual Town Hall meeting through Justice Lab, the story got out. We heard from people from all over the world, people I never thought would hear the story. Because we’re in Lafayette, the story wasn’t as big as Breonna Taylor or George Floyd. To have people out there fighting for families like mine…I never thought I’d be in that position. It makes me know that no matter what happens, it will be okay. They say sometimes justice doesn’t come in the form we want it to, but just to know that we have [people like Alanah and Maggy]out there is big for me.

I have two people I’m talking to who’ve lost their sons in different ways, but we’ve been getting together like family now. We consider one another sisters. Helping others gives me the strength to move on. Because I never want to see another family go through what I’m going through.”

Michelle Pellerin

mother of Trayford Pellerin, whom Lafayette, LA police shot 10 times in the back and killed on August 21, 2020

VS EVERYBODY and DETROIT VS EVERYBODY are registered trademarks of Detroit vs Everybody LLC.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?