Our daily attire has shifted somewhat since lockdown began in March. At first, those of us lucky enough to work from home squealed in glee at the chance to wear our pajamas all day — be gone, stuffy work shirts and restrictive trousers! — but the novelty of a nine-to-five duvet day soon wore off. We wanted to feel at least slightly presentable for Zoom calls with our manager (while maintaining the same level of comfort) and so we turned to loungewear, all color-coordinating sets, tie-dye joggers, and slogan sweaters. Of course, we haven’t taken off our humble Birkenstock sandals — the poster child of lockdown footwear — but our sartorial approach has mutated once more; on week six of lockdown, the clock has melted off the wall and with it, any sense of self.

In an effort to establish some structure in our lives, we’re searching for get-ups that still afford comfort but provide a firm start and stop to our working days. While there’s inspiration aplenty on Instagram, who better to look to for lockdown apparel than the original working from home crowd: artists and writers. Those who spend countless hours at a desk by a window with nothing but their pen and paper for company; those who emerge paint-splattered from a day in the studio, fingers cramped from the pressure of putting brush to canvas. Sure, enforced lockdown during a global pandemic is far less romantic than Joan Didion retreating to her Californian home to write, or Lee Krasner setting up residence in an East Hampton farmhouse with her husband Jackson Pollock. Unlike us, they may have been afforded agency in self-isolation but there are still things we can learn from these creatives, their working worlds, and their wardrobes.

Fashion has a long history of drawing inspiration from the work of writers and artists. Take Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. The gender- and era-defying titular character has been referenced by everyone from Burberry’s Christopher Bailey (his fall ’16 collection was all swashbuckling ruffled shirts and Renaissance-esque tapestry) to 2020’s postponed Met Gala: the theme for this year’s extravaganza, due to have taken place this week, was set to be About Time: Fashion and Duration, influenced by Tilda Swinton’s turn as Orlando in Sally Potter’s 1992 film. Elsewhere, showgoers at London Fashion Week always look forward to Erdem’s slot on the schedule thanks to his fascination with artistic figures from the past — last season, his spotlight fell on photographer Cecil Beaton and his Bright Young Things — while abstract artist Piet Mondrian has shaped the collections of designers as diverse as Yves Saint Laurent, Vivienne Westwood, and Nike.

What about the people behind the art, though? One of the most examined artists in recent history is Frida Kahlo although sadly, much like Marilyn Monroe, the iconography has almost eclipsed the Mexican painter’s work. The proliferation of gimmicky merchandise often threatens to reduce Kahlo — a revolutionary artist — to her floral crown and strong set of brows. In 2018, more than 200 possessions belonging to the artist, from her clothes and accessories to her makeup, went on display in the V&A’s blockbuster exhibition, Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up. Visitors able to look beyond the souvenirs in the museum’s gift shop found that Kahlo’s style was incredibly considered in both its political motivation and its celebration of traditional Mexican dress.

“The way she dressed sent a message about her roots and her identification with indigenous Mexican people,” Suzanne Barbezat, author of Frida Kahlo at Home, tells Refinery29. “Kahlo was upper-middle class, although her family did take economic hits after the Mexican Revolution and the painter’s various health problems. Before she married Diego Rivera, aged 22, Frida dressed in a style that was more conventional of the time and her social class.” It was after her marriage that she began to wear more traditional Mexican clothing, “at first just adding a rebozo (woven shawl) or traditional blouse, later dressing in full Mexican attire. Her outfits evoke the style of the women from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (an area which is known for having strong women — some call it a matriarchal culture) but she didn’t simply don the traditional clothing from a particular region, she would mix it up, wearing items from different regions, and she sometimes designed (and possibly sewed) her own clothing from fabric she purchased.”

When Kahlo’s health worsened and she was confined to her home after being involved in a horrific bus accident, this way of dressing — a curated and referential cultural patchwork — continued. “When her health issues became more severe later in life and she didn’t go out much, she still made a point of dressing up, styling her hair up with ribbons and flowers, doing her makeup and putting on jewelry,” Barbezat explains. “Besides sending a strong message about her national identity, the traditional Mexican clothing she favored also covered her physical impairments: the long skirts hid her legs (her left leg was shorter and thinner than the right since she had polio as a child) and the boxy blouses could fit over the medical corsets and back braces she had to wear.” In continuing to dress herself up, Kahlo not only upheld her sense of self in isolation but adapted her personal style to her new way of life.

Another artist whose style has drawn as much fascination as their body of work is American modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Unlike Kahlo, O’Keeffe has been spared the cartoonification of her image and, thanks to her husband, the pioneering photographer Alfred Stieglitz, we’re lucky enough to have a vast catalog of images of her both in and out of the studio. Over the course of their 30-year relationship, Stieglitz captured his wife and muse in powerful black and white photographs which now hang in galleries alongside O’Keeffe’s sweeping paintings of Manhattan skylines and yonic flowers. Whether in New York or New Mexico (where she would later put down roots, her work reflecting her surroundings, all cow skulls and sun-drenched landscapes), O’Keeffe’s style was pared back, functional and androgynous.

Loose-fitting white shirts, roomy skirts, slouchy cardigans, straight tunics, and wraparound robes made up the majority of O’Keeffe’s working wardrobe. Her utilitarian clothes were an extension of her general approach to art and life. Often referred to as a feminist painter, she cast off that label, preferring to be seen as simply an artist and judged for her work rather than her gender (in some ways, the most feminist of sentiments for an American woman working in the early 20th century). By adopting a minimalist, monochrome, masculine-inspired uniform, O’Keeffe took control of her personal image, enabling her work to take center stage. Nevertheless, thanks to both the quantity and composition of Stieglitz’s photographs, she’s distilled in our minds as a serene, almost religious figure: with her robe tied at the waist, white collar peeking out just so, the image of the artist has become as fascinating as the work she created. Is it a coincidence that O’Keeffe’s staid minimalism has helped to frame her as a serious artist in the canon, while Kahlo’s brightly hued and multi-printed maximalism has seen her reduced to a caricature, plastered across cushions and pencil cases?

What’s clear from studying the wardrobes of these inimitable artists and writers is both their commitment to their personal style and how it is undeniably an extension of their work. American poet and civil rights activist Maya Angelou’s wardrobe was very much rooted in the 1930s, the decade in which she grew up, and oscillated between African and European-inspired styles. In her 1969 autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Angelou ruminates on learning her approach to fashion from her mother, who made all of her childhood clothes, from bloomers and handkerchiefs to lavender taffeta Easter dresses. Part cost-effective, part self-love, as Terry Newman, author of Legendary Authors and the Clothes They Wore told Refinery29: “Looking smart and feeling good was an Angelou trademark and it boiled down to having self-respect, which was something she championed for all. Her sense of self always manifested in her wardrobe and that wardrobe was always elegant. She forever looked together.” Later in life, when working at the University of Ghana, Angelou adopted a west African style of dress that heavily featured traditional prints, two-pieces, and beaded jewelry. Her time in the country, where she met the likes of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., had a huge influence on Angelou’s writing and politics, and her dress reflected that.

Alongside her pearl necklaces, one of Angelou’s most recognizable accessories was a headscarf, currently being touted by everyone from Alexa Chung to Bella Hadid in lockdown. Yet it was not so much a stylistic choice or even a means of keeping her hair off her face while concentrating but, rather, a decision prompted by a jealous husband. Angelou told The Daily Beast in 2013:

“I was married a few times, and one of my husbands was jealous of me writing. When I write, I tend to twist my hair. Something for my small mind to do, I guess. When my husband would come into the room, he’d accuse me, and say, ‘You’ve been writing!’ As if it was a bad thing. He could tell because of my hair, so I learned to hide my hair with a turban of some sort.”

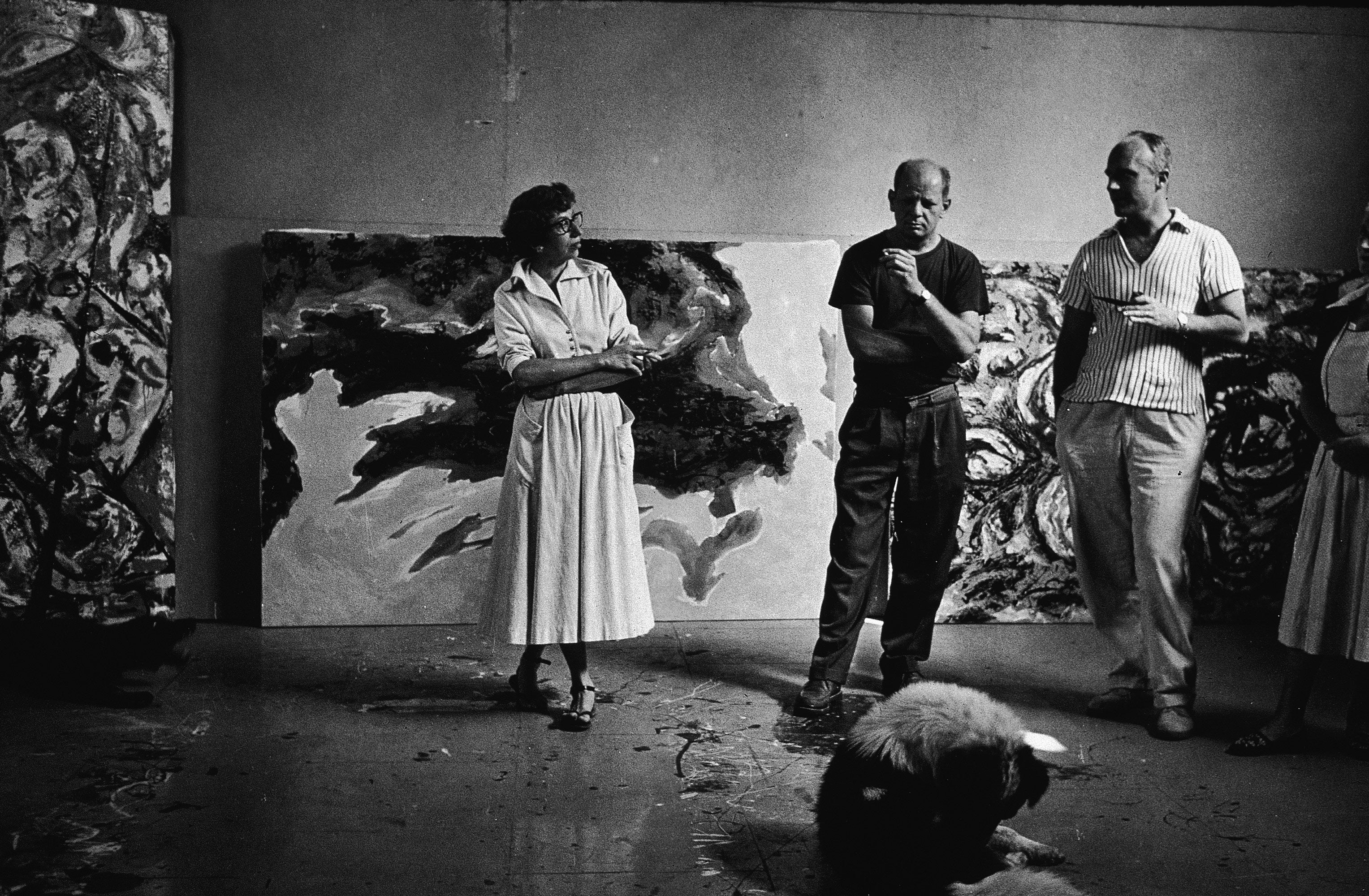

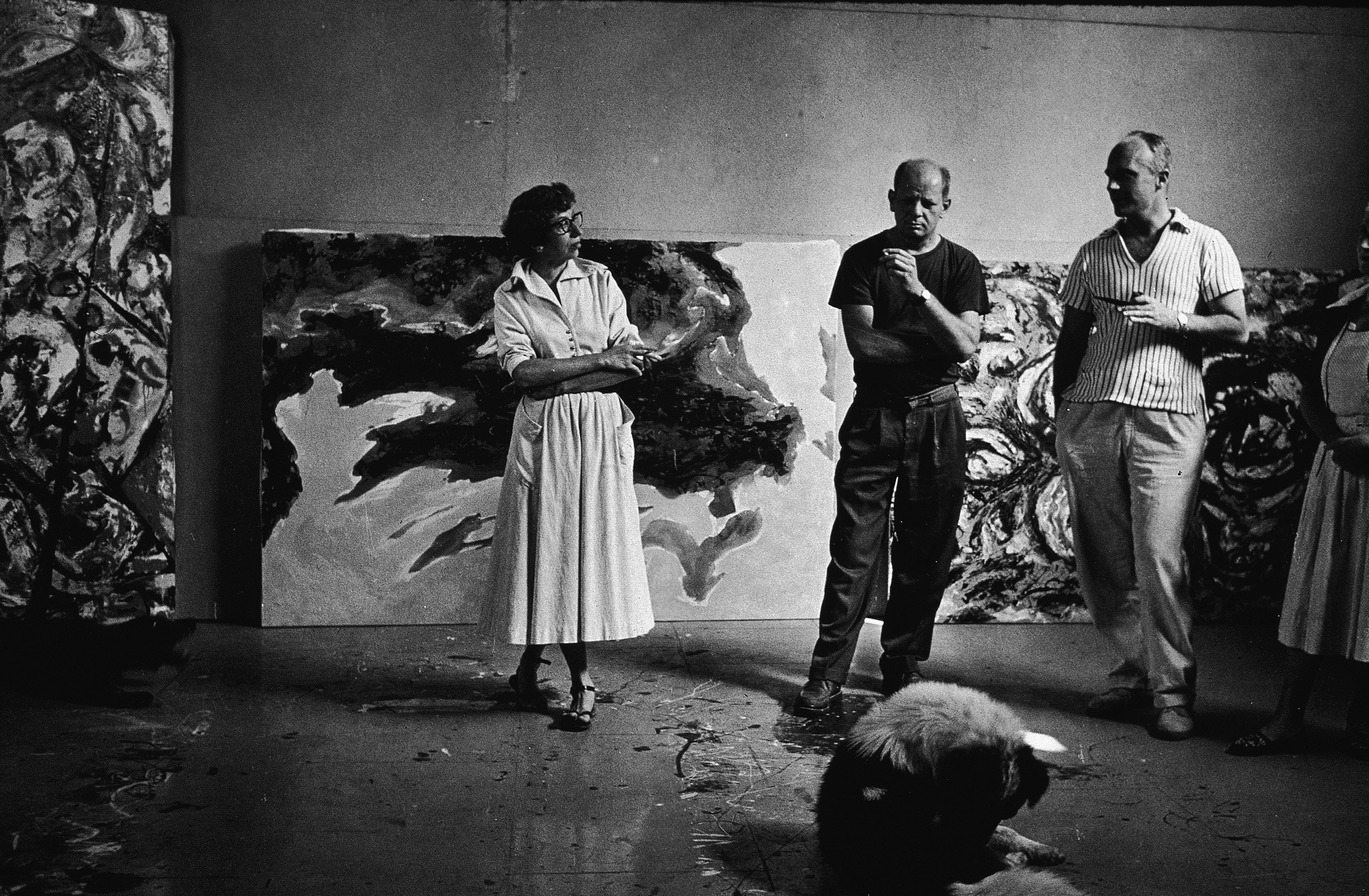

Who else can we look to for lessons in lockdown style? Lee Krasner, the great abstract expressionist painter whose life and work was eclipsed by her more famous husband Jackson Pollock until a recent retrospective at the Barbican put that to rights, favored loose shirts, ankle-skimming circle skirts (crucially, with big pockets), and capri trousers with ballet pumps. Non-restrictive, practical, and breathable, her wardrobe denoted a level of comfort conducive to the dynamic movement required to create her larger-than-life canvas paintings.

Impossibly chic writer Joan Didion, who, from her 1960s Vogue essays to 2015’s Juergen Teller-shot Céline campaign, is fashion’s most coveted and referenced muse, also demanded ease from her clothes. In a 1979 Vogue interview with the author, the journalist Georgina Howell described Didion, standing at 5’2, as “a size too small for her clothes” — but what if this oversized quality was intentional? According to Newman, “the maxi dress and flip-flops she wears in front of her Corvette in the 1968 Julian Wasser shot” was typical of her loose-fitting, easy-going style, particularly as she retreated to her San Francisco home to write. A wardrobe of simple long-sleeved black tops, calf-length skirts, and roomy column dresses – worn with flip-flops, sandals, or bare feet – made for a style that fused her time in New York with her Californian roots but put comfort above all else.

Virginia Woolf wrote in Orlando: “Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than merely to keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us.” Even more fascinating is the question of the clothes we wear when no one is watching. When self-isolating — whether for artistic purposes or because of a global pandemic — do you make yourself up to reinforce your sense of self, like Frida Kahlo? Or, like Georgia O’Keeffe and Joan Didion, do you strip things back with a fuss-free wardrobe that puts comfort first? Perhaps how we’ve found ourselves dressing in isolation will journey with us into the real world once lockdown is lifted. Perhaps not. Either way, these women, the original working from home crowd, can tell us a lot about the clothes we choose to wear when life suddenly shrinks to fit inside four walls.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Some Of You Never Learned About Inside Clothes