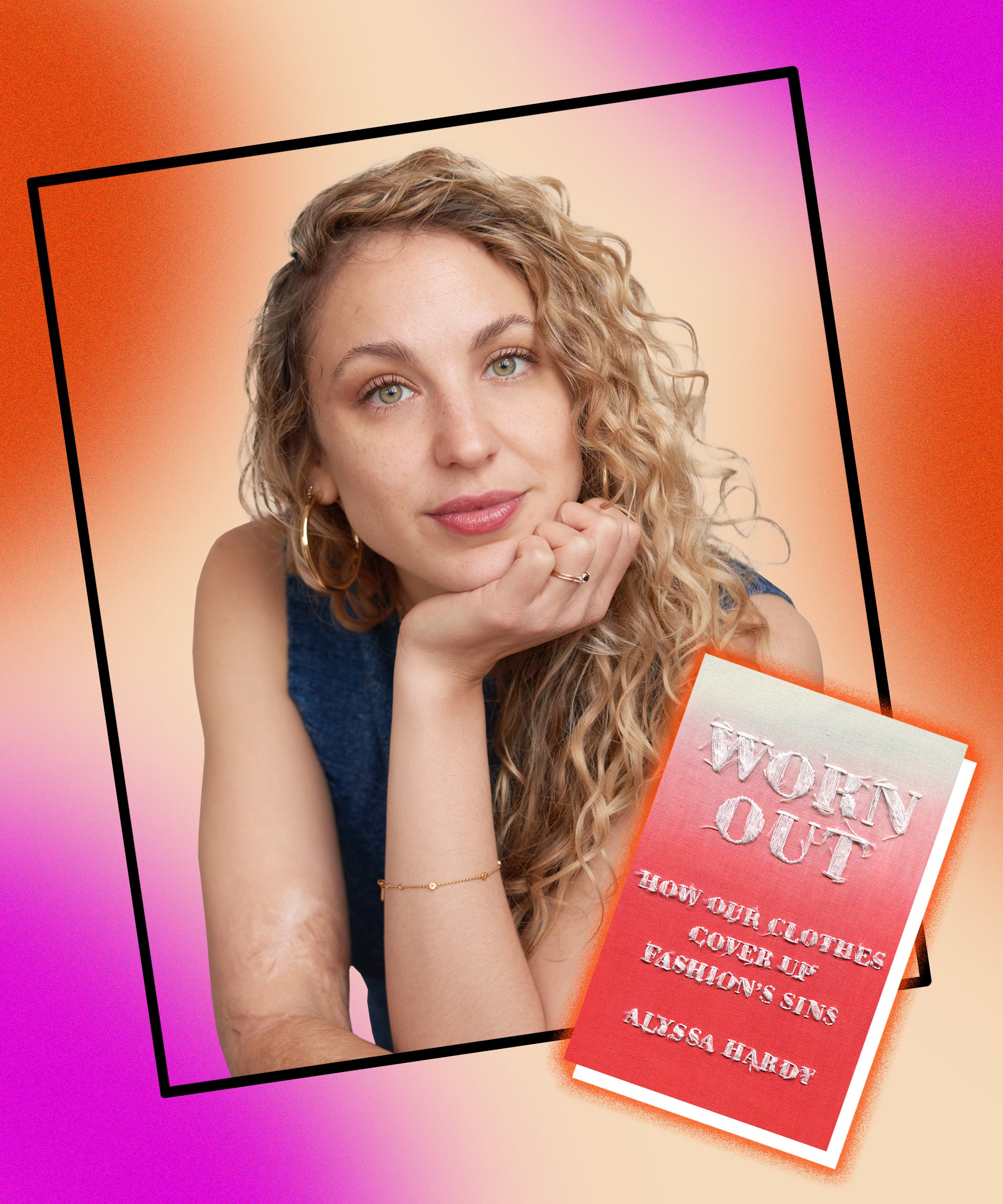

Alyssa Hardy is a freelance writer for InStyle, Fashionista, Glossy and more. She has previously worked as a fashion editor at Teen Vogue. She is also the author of Worn Out: How Our Clothes Cover Up Fashion’s Sins, which covers the labor rights movement in the fashion industry. You can follow her newsletter “This Stuff” here.

For many influencers and celebrities, a rite of passage into the fashion world is not hitting a million followers or gaining a certain amount of likes on their outfit photos. It is when they are branded; stamped and approved by a designer logo. In 2018, Kylie Jenner solidified her status as fashion elite by donning Fendi’s head-to-toe Zucca print outfit and a $12,500 matching baby carrier, provided by the brand. Others, like Emma Chamberlain, do it in subtler ways, by representing the designer they are working with as ambassadors by carrying logo-clad bags and wearing outfits that flash a quaint but visible name (in Chamberlain’s case, Louis Vuitton). It’s a marketing move that works both ways: The brand gets a new audience, and the influencer gets luxury approval.

It also makes the rest of us clamor for the same association.

In my book Worn Out: How Our Clothes Cover Up Fashion’s Sins, I wanted to highlight the relationship between logomania, influence, and consumption. I found that this seemingly simple part of the fashion ecosystem contributes to a global crisis in ways that are so hidden, they are easy to overlook if you don’t look. That’s because on a larger scale our logo obsession is the catalyst for a multi-billion dollar market of watered-down trends and cheap copies — and workers around the world are the ones who have to deal with the fallout.

Our need to consume clothing stamped with recognizable names is often driven by our desire to belong and to be seen a certain way which extends far beyond the luxury pieces themselves and drives fast trends, dupes, and counterfeiting. As the luxury accessory market is set to grow to 85 billion dollars, according to Statista, the counterfeit market will grow just as fast. A recent article on Buzzfeed highlighted an emerging trend on TikTok in which creators explain why they are turning to dupes. Brett Staniland, a model, told the outlet, “I don’t care that this is fake because I deserve to wear clothes that look good and make me feel good and celebrated regardless of whether they’re real or not.”

The general sentiment seems to be that buying fakes or fast fashion dupes is about sticking it to an inaccessible brand. The logic misses the fact that counterfeiting and cheap fast fashion dupes are only possible because workers are not paid their fair share and are often subject to horrific working conditions. Worn Out lays out different scenarios in which workers are abused and paid well below legal wages for creating these goods. In one instance, for example, a person running a workshop for counterfeit goods was arrested for abduction of the workers. Some of them were pregnant or children.

Why, then, should our need to fit into a specific aesthetic dictated to us by brands outweigh the problems this cycle causes?

As long as we prioritize access to trends over the protection of people, there will be a market for copies and incentive for the unfair labor practices used to create them. The issue comes when we look at accessibility in fashion from a hyper-individualized perspective. There is nothing morally superior about having access to a trend or brand at a lower price when the reason it’s cheaper is that the people who made it were mistreated, underpaid, and more. It’s natural to want to own something that you like, and it’s valid to feel that it’s unfair that some can buy in while others have to watch from afar. But, we need to rethink why we feel a logo is a marker of a certain level of success, and raise awareness about what it really means when we decide we have to have it no matter the consequences for others.

Alyssa Hardy’s Worn Out: How Our Clothes Cover Up Fashion’s Sins is out on September 27. You can buy it here.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?