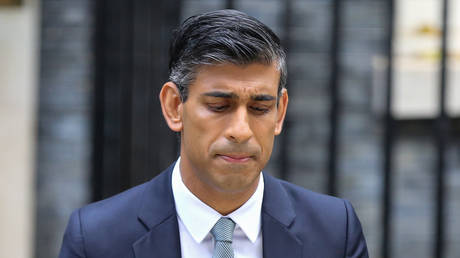

Rishi Sunak finds himself compensating for the anti-Beijing hawks in his party with his cautious engagement rhetoric

In a notable speech last week, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak declared the “Golden Age” of relations with China to be over. While he urged engagement with Beijing, he nonetheless branded it a competitor and a threat to “British values.”

Such a so-called Golden Age had been the hallmark of his Conservative predecessors, namely the government of David Cameron, who saw Beijing as an economic opportunity for Britain in terms of trade and investment. That sentiment was also briefly signalled by Boris Johnson, until the US put its foot down.

But, despite the tough-sounding speech, Sunak still found himself being branded as “weak” by right-wing anti-China MPs in his party and, worse still, accused of a U-turn by Labour. That’s because during the Conservative leadership election, Sunak seemingly presented himself as an ultra-hawk on China and branded it the biggest threat to the UK. Comparatively speaking, his recent speech was a massive climbdown.

But Beijing probably won’t be getting its hopes up. If it was not evident yet, Sunak doesn’t have a clear or consistent approach towards China. In fact, his stance is riddled with contradictions. He has done nothing to back up his calls for engagement with China, and Beijing doesn’t buy it. That’s because his actions in practice have amounted to nothing but hostility, as well as a continuing succumbing to US preferences on what the UK should or should not do.

The United Kingdom needs China, but doesn’t want to admit it. Following Brexit, the UK is seeking new trade and investment partners. It was always in the plan that China, having one of the largest consumer markets in the world, and being one of the largest investors, would be of critical importance. However, the US has succeeded in strongarming the UK, through both political and public-opinion pressure, into following its course in opposing China. This has severely limited the opportunities for Prime Ministers to engage Beijing, even if they want to.

In doing so, Washington has established an effective “veto” on what Chinese investments are allowed in Britain, and which ones are not, forcing the British government to U-turn on projects they approved not once, not twice, but three times. Each time, Downing Street mysteriously discovers “national security threats” which they had ruled out previously in approving a given project. The first example was Huawei’s participation in 5G, which the original national security review had found no problems with.

The second, just a few weeks ago, was a takeover by a Chinese-owned company of the Newport Wafer Fab in Wales. This project was approved in 2021 but then walked back a year later after American pressure, shocking the company and angering its employees. The third, happening just in the past week, was a Chinese stake in a nuclear power plant project. What these three examples show is that despite Brexit being about “sovereignty,” the United States otherwise exercises a malign sovereign influence over Britain’s trade and investment choices, forcing the UK each time to “cut its nose off to spite its face” by making self-defeating decisions which run contrary to the national interest and only suit American preferences.

In this case, it might be worth questioning who truly has brought the “Golden Era of relations” to an end? Has the UK voluntarily done so itself, or is it because the United States made them do so? Either way, this severely questions the viability of Sunak’s own bid to engage China fairly and rationally. Worse still, he now not only has to go up against opposition, not only from Washington but also from within his own party. Starting in 2020, the Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative Party, led by Iain Duncan Smith, has evolved to become the Sinophobic wing instead. Bulldozing ties with Europe has simply been replaced in their rhetoric with alienating China, and their goal, as it was for the past 30 years, is to disrupt, undermine and sabotage the government on China policy wherever possible.

And it is precisely because of this that Rishi Sunak finds himself compensating for the China hawks. He knows very well personally that China is an important economic partner for the United Kingdom, but his inability to do anything about it meaningfully, and Beijing’s growing anger with Britain, is reflective of just how little control he has over the situation.

But, quite frankly, this is the opposite of what Brexit was all about. Britain willingly gave up the right to engage with China as an independent country and, not surprisingly, finds itself much worse off for doing so.