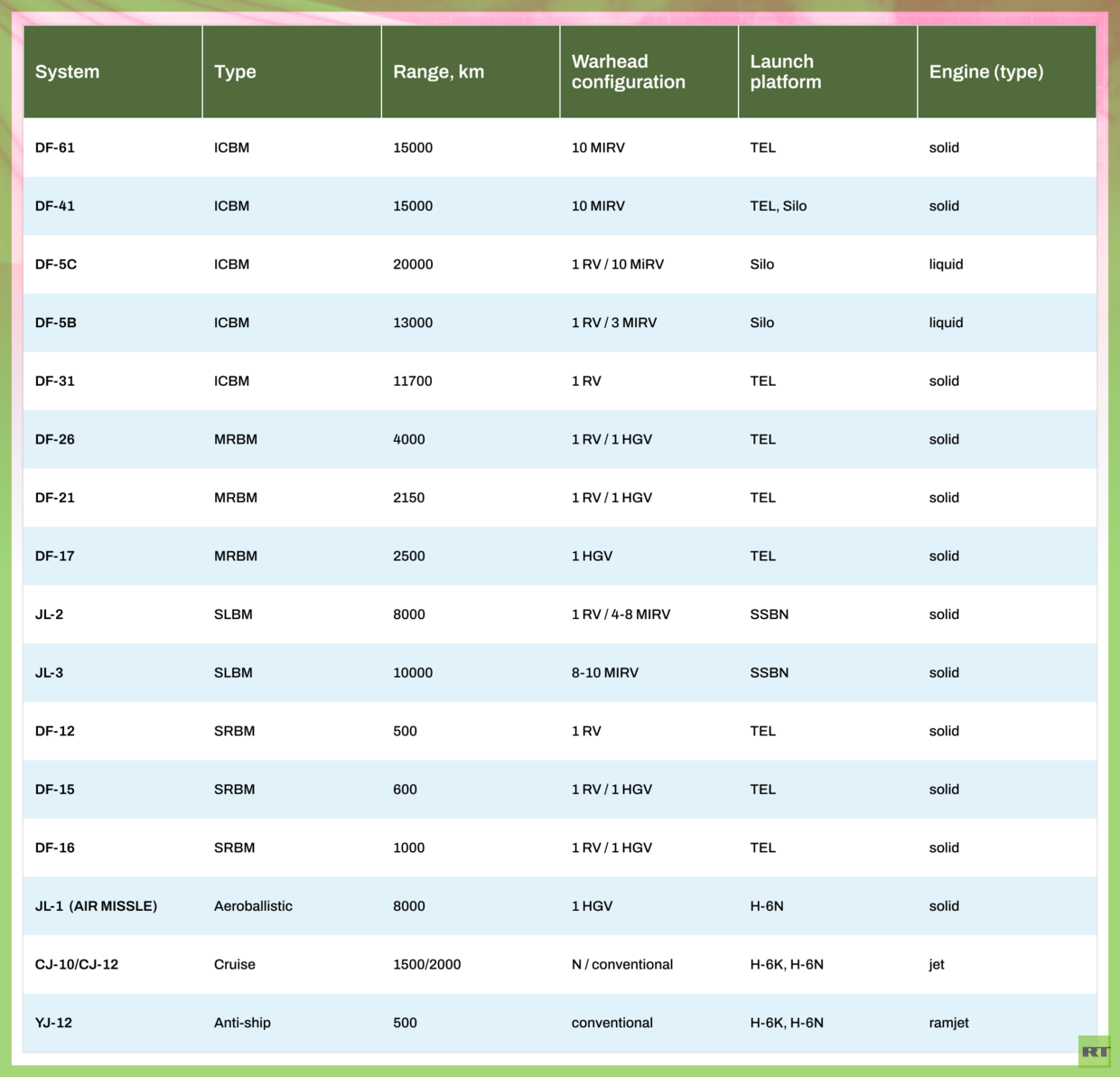

From ICBMs to hypersonic glide vehicles, Beijing has built a layered arsenal that rivals – and in some ways outpaces – the United States and Russia

Missiles are the new calling card of Chinese power. Not aircraft carriers, not tanks, not fighter jets – but rockets that can fly halfway across the planet or tear through a US Navy fleet in the Pacific.

On September 3, 2025, Beijing rolled out its arsenal in a parade that looked less like a military review and more like a warning shot. Sleek ICBMs, hypersonic gliders, and “carrier killer” missiles rumbled through Tiananmen Square, broadcasting a simple message: China has arrived, and it’s not playing catch-up anymore.

Unlike Russia and the United States, China was never shackled by Cold War arms treaties. That freedom has given the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force the widest menu of missiles in the world – intercontinental, intermediate, hypersonic, submarine-launched, even air-dropped. This isn’t just hardware. It’s Beijing’s way of telling the world: the balance of power is shifting, one rocket at a time.

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs)

China’s missile story began with reverse-engineering Soviet R-2s handed over to the PLA. Fast forward to today, and Beijing now fields the full spectrum of land- and sea-based ballistic missiles: heavy liquid-fuel silo ICBMs, mobile solid-fuel systems, and SLBMs (the naval leg we’ll cover later). Across the board, warheads can be fitted with MIRVs.

DF-61 and DF-41: China’s mobile heavy hitters

The September 3, 2025 parade featured the public debut of the DF-61, a new road-mobile solid-fuel ICBM. By appearance and scale, it looks like an evolution of the DF-41, which has been in service since 2017. The upgrade is logical: the DF-41 has been in development since 1986, and by the time it reached mass production, parts of its design were already dated. That may also explain the lag in rolling out the silo and rail-mobile versions, both tested but delayed. With DF-61, those hurdles may finally be cleared. The two systems likely share many of the same technical solutions and performance specs.

Their launchers resemble Russia’s Topol-M and Yars: eight-axle TELs carrying missiles in sealed canisters. Each missile weighs roughly 80 tons, and China almost certainly has the technology to fire them from anywhere along their patrol routes, not just prepared pads. DF-41 is thought to be bulkier than its Russian cousins and was originally designed to deliver up to 10 low-yield warheads (~150 kt each) to ranges of 12,000–14,000 km.

Western estimates suggest that since 2017, at least 300 DF-41s in various basing modes have been deployed, with the newer DF-61 now entering the mix. This blend of mobile and fixed deployments diversifies China’s deterrent and guarantees a survivable second-strike capability.

© Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

DF-5C: the silo-based giant

Parade commentary in Beijing described the DF-5C as able to hit “any target in the world,” with a range up to 20,000 km. In Russian parlance that would qualify as a “global missile,” though technically that term often refers to systems that loft payloads into near-Earth orbit before de-orbiting. The mismatch here likely comes down to translation rather than capability.

The DF-5C is the latest version of the liquid-fuel DF-5, which first flew back in 1971. Technologically, it sits in the lineage of late-1960s Soviet R-36 designs, while the DF-5C might more closely resemble the R-36M2 “Satan.” First tested in 2017, it’s reported to carry 10–12 medium-yield warheads and is based in silos. Today, China fields about 20 of these missiles.

DF-31 family: China’s first solid-fuel road-mobile ICBM

China’s first road-mobile solid-fuel ICBM, the DF-31, is often described as Beijing’s version of Russia’s Topol: a three-stage missile with a 12,000 km range and a single 200–300 kt warhead. Developed through the 1990s and 2000s, it entered service in 2006.

The DF-31AG, first sighted in 2017, made its parade debut in September 2025, mounted on a beefed-up multi-axle TEL that echoes the DF-41. A more advanced variant, the DF-31BJ, was also displayed; its notably longer canister has fueled speculation it carries a hypersonic maneuverable warhead. In total, more than 80 DF-31-series missiles may be deployed across China.

© VCG/VCG via Getty Images

Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs): JL-2 and JL-3

Since the 1990s, China has been building out the sea leg of its strategic forces: nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines armed with solid-fuel SLBMs. Since 2007, the PLA Navy has operated Type 094 SSBNs, each carrying 12 JL-2 missiles. Six boats are in service today, with two more under construction.

The JL-2 draws on technology from the DF-31 – and likely the DF-41—ICBMs. It offers a range of up to 8,000 km and can carry either a single megaton-class warhead or up to eight MIRVed warheads.

Beginning in 2022, JL-2s have reportedly been gradually replaced by the more advanced JL-3, which shares similar dimensions. The JL-3 made its public debut at the September 3, 2025 parade. Estimates put its range at about 10,000 km, with MIRV payloads as standard.

With the new Type 096 SSBNs already under construction, it’s clear Beijing is prioritizing the maritime component of its strategic nuclear forces.

Intermediate- and Medium-Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBM / MRBM) & Hypersonics

Before diving into the intercontinental heavyweights, it’s worth pausing on the class of missiles that may matter most in a real fight over Taiwan or the South China Sea: intermediate- and medium-range systems. Unlike the United States and Russia, which were long constrained by the INF Treaty, China never faced limits on building weapons in the 500–5,500 km range. That freedom has given Beijing a decisive edge across Asia. These missiles form the backbone of its regional strike force – designed to hold US bases, allied infrastructure, and naval task groups at risk – and they’ve become the sharpest tool in China’s anti-access/area-denial strategy.

DF-26 and DF-21 – the region-shapers

The DF-26 has earned a blunt nickname: the “carrier killer.” This two-stage, solid-fuel intermediate-range ballistic missile can reach up to ~4,000 km and is fielded in variants with either conventional or nuclear payloads. One variant is believed to carry a hypersonic maneuverable warhead designed to engage moving maritime targets – a capability that directly threatens carrier strike groups and gives Beijing a potent anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) tool.

The DF-26 began entering service in 2016 and is gradually replacing the older DF-21, China’s first solid-fuel medium-range missile adopted in the early 1990s. The DF-21 family still exists in multiple configurations; the text estimates at least ~80 DF-21 systems deployed in various roles. Together, DF-21 and DF-26 mobile launchers give China reach across Southeast Asia, much of the western Pacific, and even into parts of Russian territory – a geographic coverage that reshapes operational options across the region.

© Andy Wong – Pool /Getty Images

DF-17 – China’s fielded hypersonic glide vehicle system

China tested its first hypersonic glide vehicle concept in 2014, apparently using a DF-16 booster. Mobile systems carrying the DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle entered service from 2019. What makes the DF-17 notable is not simply speed but maneuverability: the glide vehicle flies at hypersonic speeds along the edge of the atmosphere and can maneuver both laterally and vertically, complicating tracking and interception for modern missile-defense systems.

Reported performance figures put the DF-17’s effective range at about 2,500 km, with payloads (even conventional ones) delivered at speeds exceeding Mach 5. While that range limits oceanic reach, it enables strikes across coastal waters and land areas well within China’s periphery – precisely the zones Beijing is most likely to contest. Open estimates suggest several dozen DF-17 units are deployed today.

Hypersonic glide vehicles like the DF-17 are expressly attractive because they compress decision time for defenders and reduce the effectiveness of interception architectures that rely on predictable ballistic trajectories. That is why China has prioritized them as part of the layered deterrent and area-denial posture.

Air-launched Missile Systems (JL-1, H-6 / CJ-10 / YJ family)

China’s strategic missile posture isn’t limited to silos and submarines – the PLAAF also fields a heavy air-launched arsenal built around the venerable H-6 bomber family. The H-6N, the most advanced variant on display, serves as the launch platform for a new generation of air-dropped ballistic and cruise missiles, extending Beijing’s strike reach well beyond coastal waters.

JL-1: a new air-launched ballistic option

At the September 3 parade Beijing unveiled the JL-1 (Jīng Léi-Yī), a two-stage air-launched ballistic missile carried by the H-6N. The JL-1 is launched from a pylon under the aircraft and then follows a ballistic arc to its target. Each H-6N can carry a single JL-1, and pairing the missile with the bomber yields a strike radius of up to ~8,000 km – sufficient for precision strikes against naval task forces and fixed targets across long distances. Deployment of JL-1 within PLAAF strategic aviation appears to be underway this year.

H-6 as a versatile missile truck

The H-6 family, essentially a domestic evolution of the Soviet Tu-16, remains China’s principal long-range bomber fleet. Modern H-6 variants can carry a variety of payloads under the wings, including CJ-10/CJ-12 cruise missiles (descended from Soviet Kh-55 tech captured after the USSR collapsed). These subsonic cruise missiles – with ranges in the 1,500–2,000 km band – trade speed for payload and endurance, letting H-6s strike fixed targets or naval assets at standoff ranges, albeit at the cost of reduced ferry range for the bomber itself.

YJ family: supersonic and hypersonic anti-ship missiles

Most worrying for surface fleets is China’s growing inventory of high-speed anti-ship missiles. The H-6 can carry the YJ-12, a supersonic anti-ship missile with reported speeds between Mach 2.5 and Mach 4 and a range up to ~500 km – performance that narrows the window for naval defenses. At the Beijing parade, China also showcased a family of next-generation missiles – YJ-15 and possible YJ-17, YJ-19, YJ-20, and YJ-21 – some of which appear to be supersonic or hypersonic designs. The YJ-17 reportedly uses a two-stage booster and a hypersonic glide vehicle to push ranges toward ~1,000 km; the YJ-19 is said to employ a scramjet and to operate in the ~500 km class; YJ-20 and YJ-21 resemble aeroballistic or aeroballistic-style missiles with 300–400 km reach similar in role to Iskander-M or Kinzhal. Many of these may still be prototypes, but their public appearance signals China’s emphasis on fast, hard-to-intercept anti-ship and coastal-defense weapons.

Taken together, the H-6 fleet and its missile family give China the ability to strike across much of the western Pacific from land bases – a capability central to any PLA campaign to control nearby seas or threaten distant task groups.

© Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Short-Range missiles – the Taiwan toolbox

While the ICBMs and hypersonics draw headlines, China’s short- and medium-range ballistic missiles are the instruments most likely to be used in a regional fight – especially over Taiwan and in the South and East China Seas. These systems are purpose-built to deny access, saturate defences, and cripple launch or basing infrastructure before an adversary can respond.

China fielded the DF-12 in 2013: a modern, high-precision tactical missile system that – by many accounts – outperforms US ATACMS in range and mobility. Launched from inclined transport-launch containers on a four-axle chassis, DF-12 rockets can reach 400–500 km. Beijing also exports an M20 derivative for the Belarusian Polonez launchers with a reduced ~300 km range.

Complementing DF-12 are short-range solid ballistic systems such as the DF-15 (up to 600 km) and the DF-16 (around 1,000 km). Both families come in multiple variants and can be fitted with conventional or nuclear warheads – including precision, terminally guided payloads that improve hit probability against point targets. Put together, the PLA likely operates hundreds of launchers for these systems.

That density and depth of launchers matter. In any operation aimed at Taiwan, the PLA could employ massed strikes with SRBMs and MRBMs to suppress air defences, blind surveillance systems, and batter runways and ports. The integrated use of these missiles – layered with cruise and anti-ship systems – would make sustaining an effective defensive posture extremely difficult for any opponent.

At the 2025 parade Beijing also highlighted supersonic and hypersonic anti-ship missiles with reported ranges up to 1,000 km (YJ family). Even if some items remain prototypes, the trend is clear: China is stacking its littoral and theater forces with fast, hard-to-intercept weapons that complicate naval operations in the first island chain.

From catch-up to takeover

China’s missile arsenal today is not just catching up with the world’s leading nuclear powers – in some areas, it’s already out in front. The sheer variety of systems on display in Beijing – from heavy silo ICBMs to road-mobile launchers, from submarine- and air-launched systems to hypersonic glide vehicles and supersonic anti-ship weapons – points to a layered, flexible, and modern strategic deterrent.

In fact, Beijing is pressing hardest in the one domain where its rivals lag badly: hypersonics. While Washington is still in the research-and-testing phase, China fields operational hypersonic glide vehicles and is expanding its hypersonic anti-ship arsenal. Russia is the only other country in that club, and both Moscow and Beijing are moving faster than the United States.

The September 3, 2025 parade wasn’t just pomp. It was a signal. China is building a missile force designed not only to guarantee a second strike in nuclear war, but also to deny access to its coastal zones, threaten adversary fleets, and keep rivals guessing in any regional conflict. For the first time in modern history, Beijing isn’t playing catch-up in missile technology. It’s setting the tempo – and daring others to keep pace.