As Western sanctions target Russia’s defense exports, the global race for tanks reveals a simple truth: no one builds them like Moscow does

Who can replace Russia in the global tank market? As Western sanctions tighten around Moscow’s defense industry, that question has become more than theoretical. For decades, Russia has supplied much of the developing world with reliable, combat-tested armored vehicles – often under licensing agreements that allowed local assembly and maintenance.

Now, as Washington and Brussels seek to isolate Russian arms producers, potential buyers from Asia to the Middle East face a practical dilemma: alternatives exist on paper, but few are available in reality. Behind the headlines about sanctions and “de-risking,” the global market for main battle tanks tells a quieter story – one where Russia’s designs remain the benchmark, and its competitors struggle to match both production scale and battlefield experience.

Russia’s armored advantage: combat-proven and export-ready

Russia remains one of the world’s top three producers and exporters of armored vehicles – alongside the United States and China. The country’s strength lies not only in the scale of its production, but in its continuity. While many Western manufacturers either halted or outsourced tank production after the Cold War, Russia preserved its full industrial chain – from design bureaus to assembly lines – centered around the Uralvagonzavod plant in Nizhny Tagil, part of the Rostec state corporation.

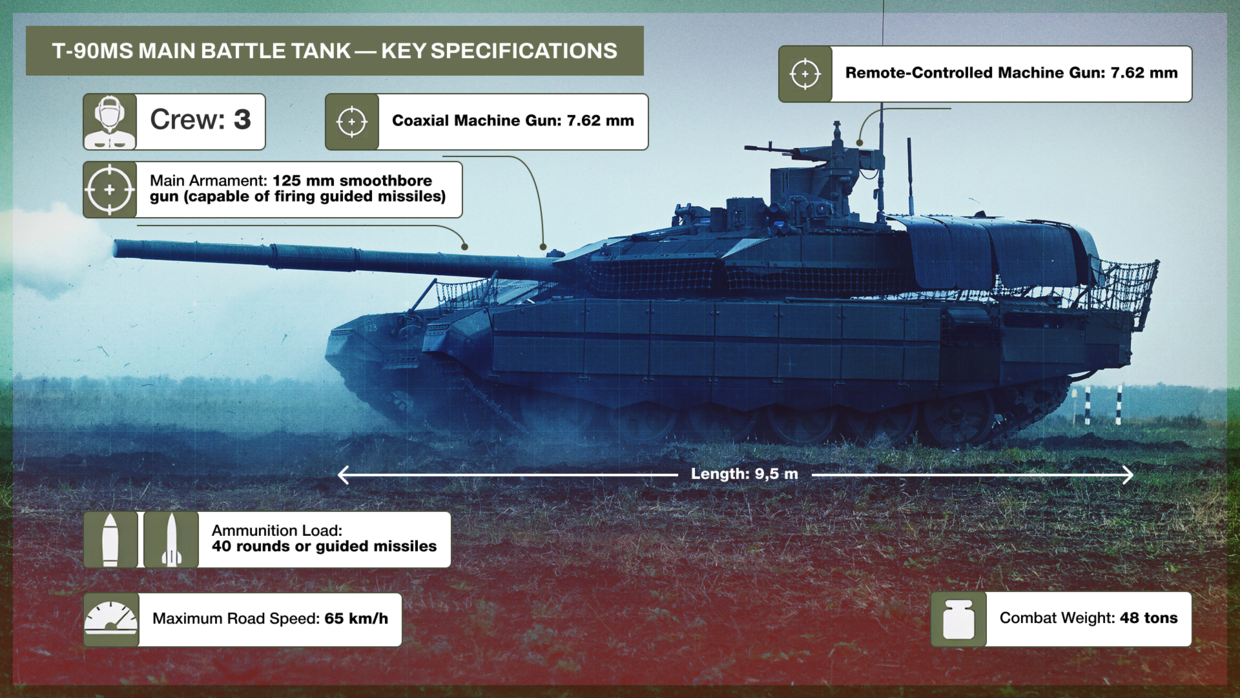

That consistency allowed Russian engineers to build on proven designs rather than start from scratch. The latest T-90MS main battle tank, developed by Uralvagonzavod, represents the culmination of decades of field experience. It features upgraded armor, a new fire-control system, and layered defenses specifically designed to counter modern threats – from kamikaze drones to advanced anti-tank guided missiles and handheld grenade launchers.

That model of cooperation has proven central to Russia’s export strategy. Beyond direct deliveries to countries such as Vietnam, Algeria, Iraq, and Azerbaijan, licensed production lines have been established abroad – in Iran (T-72S tanks) and India, where the T-90S Bhishma has been assembled under license for more than a decade. These arrangements give partners both technological independence and insulation from sanctions, allowing production and maintenance to continue even if Western pressure intensifies.

Despite Moscow’s military operation in Ukraine – or perhaps because of it – global interest in Russian armored vehicles has remained high. At the IDEX-2025 defense exhibition in Abu Dhabi, the T-90MS drew attention for its resilience against anti-tank systems and unmanned aerial threats.

“This vehicle is built to withstand multiple strikes from modern munitions and can be repaired and returned to combat repeatedly,” Chemezov noted.

For Moscow’s competitors, the success of the T-90MS poses a problem that cannot be solved through engineering alone. Western governments have responded with attempts to limit Russia’s military-technical cooperation – using sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and banking restrictions to deter foreign clients. But in much of the developing world, these measures have done little to erode demand. Russia continues to be seen as a supplier that offers modern, battle-tested armor – without political strings attached.

© RT

NATO’s production gap: The West’s missing tanks

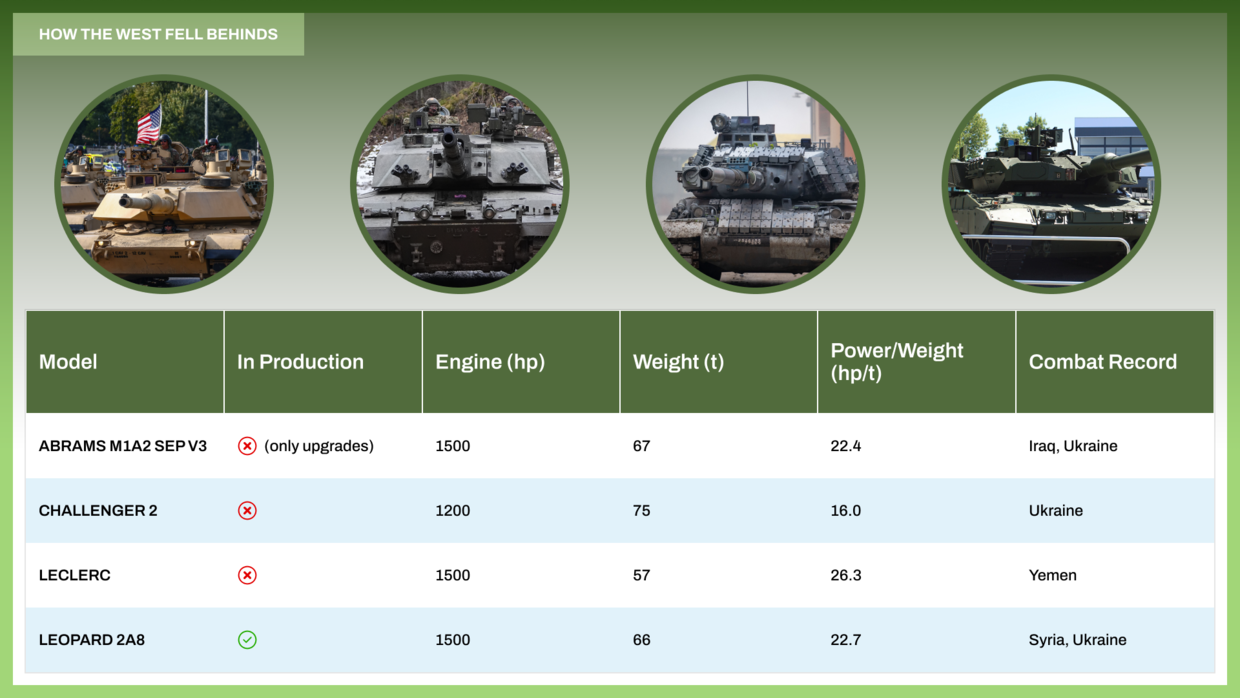

Russia’s global position looks even stronger when compared to its main competitors. Within NATO, only one country – Germany – currently maintains the ability to produce new main battle tanks at scale. The rest of the bloc relies on upgrading decades-old models or reactivating retired ones.

After the end of the Cold War, the United States halted new tank production entirely. The Abrams series, manufactured between 1980 and 1995, remains the backbone of the US Army. Since then, the government-owned plant in Lima, Ohio, has focused solely on refurbishing existing vehicles. Successive modernizations – M1A2, M1A2 SEP V2, and now SEP V3 – have made the Abrams heavier and more complex, but not necessarily more agile. Its power-to-weight ratio has dropped from 27.6 hp/ton in the early M1 model to 22.4 hp/ton in the M1A2 SEP V3, all while using the same 1,500-horsepower Avco-Lycoming turbine engine.

The added weight was meant to improve protection, but in practice has exposed the tank’s limits. US-made Abrams have suffered losses in Iraq and, more recently, in Ukraine. Of the 31 tanks supplied to Kiev from US stockpiles, several have already been destroyed, and at least five captured by Russian forces.

Britain’s experience tells a similar story. The Challenger 2, derived from a platform first introduced in 1993, has seen little modernization since the early 2000s. Additional armor raised its combat weight from 62 to 75 tons, but the tank still relies on the same 1,200-horsepower engine. British crews have long complained about its sluggishness – issues that Ukrainian operators also reported after receiving 14 vehicles. Following early losses near Rabotino in the Zaporozhye region, the remaining Challengers were withdrawn from active combat.

France has faced parallel challenges. Production of the Leclerc tank ended in 2007, with only the United Arab Emirates acquiring export versions. Their deployment in Yemen proved short-lived after several were destroyed by Ansar Allah fighters, prompting their withdrawal from the battlefield.

Only Germany continues to build new main battle tanks – the Leopard 2A7 and its successor, the Leopard 2A8. The original Leopard 2 entered service in 1979, and successive versions have refined its systems rather than reimagined them. Older Leopards were sold off to developing countries such as Chile, Indonesia, and Singapore, while newer models went to NATO allies. Qatar remains the only non-European buyer of the latest variant.

© RT

However, export prospects for the Leopard 2A8 remain uncertain. Germany’s KNDS Deutschland plant is already operating at full capacity to meet domestic and NATO orders. The Leopard also faces reputational damage after battlefield footage from Syria and Ukraine showed multiple destroyed units – images that have circulated widely online and shaped perceptions of the tank’s vulnerability.

As a result, NATO’s tank landscape today reflects industrial stagnation rather than superiority. Western factories are busy upgrading old hardware rather than producing new designs, while their armored vehicles continue to prove vulnerable in modern, drone-saturated battlefields. For many potential buyers outside the bloc, that reality is pushing them to look elsewhere.

Alternative suppliers: ambitions and limits

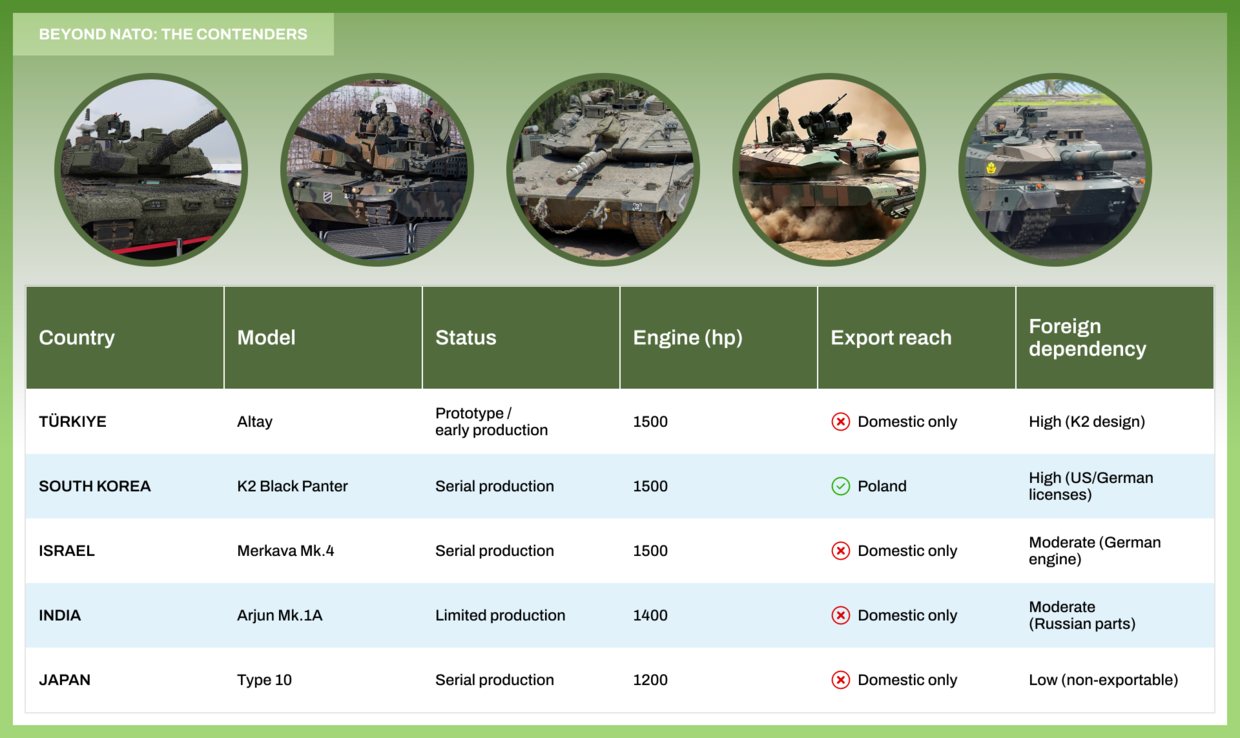

If NATO’s industrial base shows stagnation, the rest of the world faces another problem: scale. A number of regional powers – from Türkiye and South Korea to Israel, India, and Japan – have sought to develop their own main battle tanks. Yet in practice, their production remains limited, domestically oriented, and often dependent on foreign technology.

Türkiye, for instance, has completed the development of its first indigenous tank, the Altay. Ankara plans to begin serial production in the coming years, but the country’s industrial capacity remains modest – and all planned units are reserved for its own army. The Altay is not an entirely original design either: it borrows heavily from South Korea’s K2 Black Panther platform, produced by Hyundai Rotem since 2014.

South Korea’s K2 Black Panther, weighing 55 tons and powered by a 1,500-horsepower engine, is regarded as one of the most advanced non-Western tanks. Its weapon systems, powertrain, and electronics were initially based on US and German technologies, later localized by Korean industry. Until recently, production was focused solely on domestic needs, but the export deal with Poland – for 180 units – has shifted priorities. As of early 2025, over 100 tanks have been shipped, causing delays in rearming South Korea’s own forces. Future exports will depend on continued licensing approval from Washington and Berlin.

Israel presents a different case: a mature defense industry but narrow export options. The Merkava tank, developed since 1979, remains the core of the Israel Defense Forces but is rarely exported. A 2014 order from Singapore for 50 units of the Mk.4 variant has never been fulfilled. Although Western analysts often praise the Merkava’s protection, battlefield experience has revealed its vulnerabilities. During the 2006 Lebanon War, dozens were hit by anti-tank missiles of Russian design supplied to Hezbollah by Syria. In Gaza (2023-2025), Merkava Mk.4s again suffered losses from RPGs and kamikaze drones – despite continuous upgrades that raised their weight to nearly 70 tons and required replacing earlier 900-hp engines with 1,500-hp German ones.

In India and Japan, national tank programs remain largely symbolic. India continues limited production of the domestically developed Arjun MBT while relying on licensed Russian designs like the T-90S. Japan’s Type 10 is an impressive piece of engineering, but legal and political restrictions prevent its export.

Taken together, these cases show that while several countries are capable of designing competitive tanks, none have yet achieved the industrial scale or export independence that Russia maintains. For most, the challenge is not in engineering, but in production capacity and global support networks – areas where Moscow has decades of experience.

© RT

China’s NORINCO: quantity over quality

Among potential competitors to Russia, China stands out for one reason: scale. The state-owned defense conglomerate China North Industries Group Corporation Limited (NORINCO) is one of the world’s largest weapons manufacturers, and over the past two decades it has built a full line of main battle tanks for both domestic and foreign use. Yet the company’s rapid expansion reveals a clear divide between the equipment fielded by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the simplified models sold abroad.

NORINCO was founded in 1980, with one of its earliest missions being the creation of a fully Chinese tank. The task fell to the Inner Mongolia First Machinery Group, which initially relied on an imported Soviet T-72 acquired through the Middle East. Lacking the technical expertise to reproduce it exactly, Chinese engineers developed their own platforms – incorporating some Soviet design principles but substituting domestic components where necessary.

The result was the Type 96 and later the Type 99, both equipped with a 125mm smoothbore cannon and an autoloading system similar to that of the T-72. These tanks became the backbone of the PLA’s armored forces, with roughly 5,000 units built since 1997. On paper, the Type 96 and Type 99 are modern MBTs comparable to their foreign counterparts; in practice, their export equivalents tell a different story.

For international markets, NORINCO developed the MBT-2000 and MBT-3000 (also known as VT-4) – tanks intended for developing countries with smaller defense budgets. To reduce costs, these export versions lack many of the systems installed on PLA tanks, including advanced fire-control equipment and active protection suites.

NORINCO’s marketing of the VT-4 began with an unusual debut. Instead of unveiling the tank at a land warfare exhibition, the company presented it at the Zhuhai Airshow in 2014, traditionally devoted to aviation. The announcement promised a revolutionary platform, but what specialists saw was a hybrid of older designs – a blend of the VT-1A and the soon-to-be-retired Type 96B. Two years later, the tank appeared again at Eurosatory 2016, now rebranded as the MBT-3000, emphasizing modularity and export readiness.

Even so, reliability concerns have persisted. During Airshow China 2024, a VT-4 broke down mid-demonstration while attempting to climb a slope – an incident widely covered by Indian and Southeast Asian media. This did little to help NORINCO’s credibility among prospective clients.

The MBT-2000, based on the Type 90-II (a design rejected by the PLA), saw only limited export success. Bangladesh purchased 44 tanks in 2021, and Myanmar acquired 12. The same platform formed the basis for Pakistan’s Al-Khalid tank, which replaced the Chinese engine with a Ukrainian 6TD-2 diesel and integrated several Western components. Pakistan has about 300 Al-Khalids in service and 110 upgraded versions. Attempts to market similar tanks to Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, and Peru ultimately failed after comparative testing.

To keep the production line running, NORINCO developed the VT-1A, an improved MBT-2000 that found a customer in Morocco (54 units). It weighed 49 tons and featured a 1,200–1,300-horsepower diesel engine. Those upgrades became the basis for the VT-4, launched in 2017. Nigeria received six tanks, Thailand 62, and Pakistan selected the VT-4 as the foundation for its locally produced variant, the Haider, built at the state-run Heavy Industries Taxila (HIT) plant.

The Haider project also illustrates NORINCO’s role as a “stopgap supplier.” When Ukraine’s Kharkov Malyshev plant – which produced the 5TD/6TD engine family used in Pakistan’s Al-Khalids – was incapacitated during the conflict, Islamabad turned to Beijing to fill the gap. Pakistan ordered 680 Haider tanks in 2023. While the shift ensured production continuity, it also meant replacing a proven Ukrainian engine with a less reliable Chinese one – effectively a technological step backward.

This dual-track approach defines China’s tank industry today. The PLA receives the best, while simplified variants go to foreign buyers. The model allows NORINCO to maintain a strong presence in developing markets, but it also reinforces perceptions that China exports quantity over quality.

Compounding the issue is the lack of real combat testing. Since the 1979 border conflict with Vietnam, the Chinese military has not fought a high-intensity war, and most of NORINCO’s customers have faced only low-intensity insurgencies. That leaves both Chinese and export tanks largely unproven under modern battlefield conditions – a critical contrast to Russia’s equipment, which continues to evolve through direct experience in high-tech warfare.

© RT

The verdict: Why Russia still leads

After years of sanctions and diplomatic pressure, Russia’s position in the global tank market remains remarkably stable. Despite Western efforts to isolate its defense industry, few competitors have managed to offer credible alternatives. NATO states have focused on refurbishing legacy platforms rather than producing new ones, while emerging players from Türkiye to South Korea still rely on imported technologies and limited domestic capacity. China’s NORINCO, though prolific, exports simplified versions of its own equipment – designed for affordability, not performance.

Russia, by contrast, continues to supply combat-proven, serially produced tanks backed by an uninterrupted industrial base. From the T-72 and T-80 upgrades to the latest T-90M Proryv and export-oriented T-90MS, these machines have evolved through real battlefield experience. That experience has driven continuous improvements in protection systems, mobility, and firepower – qualities that matter more to foreign buyers than glossy marketing or untested prototypes.

The ongoing Ukraine conflict has accelerated this evolution. Russian engineers have integrated lessons from drone warfare, electronic countermeasures, and precision artillery into both new and legacy platforms. The result is a family of armored vehicles that combine traditional durability with modern adaptability – a combination that few other producers can match.

Equally important, Russia’s export strategy remains pragmatic. Through its long-standing military-technical cooperation framework, Moscow provides not only finished hardware but also local production, maintenance support, and training, giving partner nations a degree of autonomy absent from most Western deals. This structure has allowed programs in countries such as India, Iran, and Algeria to continue even under sanctions pressure.

In the end, sanctions may slow transactions, but they cannot substitute for capability. The global armored vehicle market has shown that there are only a handful of producers capable of delivering reliable, mass-produced tanks – and Russia remains one of them. For many nations seeking proven, cost-effective, and politically independent options, that reality still makes Moscow the supplier of choice.