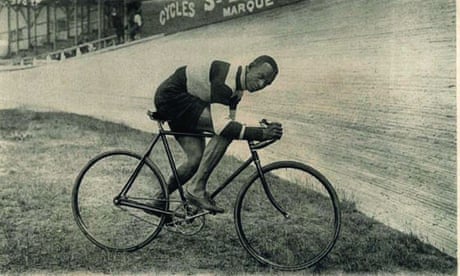

Cyclists such as sprint world champion Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor were early stars of the sport in the US. But many felt compelled to move abroad

When cycling first took the US by storm in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Black Americans joined in the new pastime. One Black cyclist, Marshall “Major” Taylor, became a world champion in 1899. Yet American cycling installed a color line in professional racing. Opportunities became so limited that Black competitors had to take them wherever they could find them – including on the vaudeville stage and in Europe. Their story is documented in a new book, Black Cyclists: The Race for Inclusion, by Robert J Turpin, a professor of history at Lees-McRae College in North Carolina.

“We fall into the trap that history is linear,” Turpin says. “With race relations, we think about the end of the Civil War: ‘Slavery ended, and things gradually got better and better for Black people.’ My book shows what we already know: Things actually got worse for Black people in the US, especially from the 1880s through the 1920s … It got harder for Black cyclists to compete as professionals or even win prize money in general.”