ARLINGTON, Texas – At the end of a trying 2015 season, Whit Merrifield was ready to walk away from baseball.

His confidence had been shaken the previous fall, when the Kansas City Royals didn’t add him to their 40-man roster and no team picked him in the Rule 5 draft after he’d batted .340 at triple-A Omaha. A strong camp the following spring, in which he’d been the last cut, restored some of his lost faith.

But then on the night of July 8, shortly after Alex Gordon was carted off the field in Kansas City with a groin injury, he was pulled from a game and told he was going to The Show, only for the promotion to be rescinded once his bags were packed. Three weeks later, the Royals acquired Ben Zobrist before the trade deadline, there was no September call up for Merrifield and he felt more off the grid than ever as the big-league club won the World Series. “Maybe,” Merrifield recalls thinking, “I can’t play at that level.”

Before definitively making the call to retire, Merrifield sat down with his dad Bill, whose pro career had all kinds of parallels to that of his son. He was also 25 when he had a big-league promotion pulled out from under him. Bill was in the starting lineup for the Pittsburgh Pirates before a rain delay gave them time to rethink things and send him to the fall instructional league. He then decided to quit midway through the next year at 26.

In that way, Bill could offer his understanding and insight as both a parent and a baseball player. Their subsequent conversations changed the course of Merrifield’s career and his life, and on Father’s Day, offer a poignant example of the power in some timely advice, and in the relationship between parent and child.

“I mean, he was pretty integral,” says Merrifield. “When I was 12 years old, he coached our travel team and I didn’t really play because I wasn’t one of the best nine players. He kept me in that, you’ve-got-to-earn-everything-you’re-going-to-get mentality. We’ve always had a unique relationship that’s transformed over the years. But he’s always been my coach in everything.”

Says Bill, who is now Wake Forest’s assistant athletic director: “When I finished playing baseball, I was done. I knew I didn’t want to do it anymore. I didn’t miss it one day once I got out. I think he would have missed it and he realized that.”

Amid the frustrations Merrifield was feeling back in the fall of 2015, he needed some help in finding reasons to keep going.

Though he entered pro ball with some momentum, he was a key player at the University of South Carolina and his walk-off single won the College World Series in 2010, his runway was limited as a ninth-round pick who signed for $100,000. It took him four years to touch triple-A and his style of play – win-first, numbers-second catalyst at the plate, chaos-maker on the bases, versatile defender capable at multiple positions – meant his stat line didn’t always accurately reflect his impact.

The transition to the minor-leagues after three years at South Carolina, where the people of Columbia gave the experience of playing for the Gamecocks a big-league feel, had been jarring. When Merrifield arrived at low-A Burlington in Iowa after being drafted, for instance, he was picked up by a clubhouse attendant in a beat-up sedan with no air conditioning and dropped off at an apartment complex where he shared a two-bedroom unit with five teammates. When he asked where to set up, one of them pointed to a gap on the floor.

Merrifield grinded through it but grew increasingly frustrated as teammates he felt weren’t as impactful as he was kept getting promoted to the majors while he didn’t. The 2014 season, when he batted .340/.373/.474 in 76 games with Omaha after an early-season promotion from double-A, left him feeling like he was on the cusp but not being added to the 40-man roster really made him question if he was as good as he thought he was.

He persisted through that, but then the phantom promotion in the summer of 2015 “kind of crushed me.”

Playing in Omaha against Iowa, he worked a fifth-inning walk, advanced to second on an errant pickoff throw, scored on a Rey Fuentes base hit and then was abruptly pulled from the game. Confused, he pleaded his case to manager Brian Poldberg, saying he was good to play the field after an awkward slide into home plate.

“No, you’re out,” replied Poldberg. “Alex Gordon just got carted off the field in Kansas City.”

Oh, damn, Merrifield thought to himself and a parade of hugs began. He scurried into the clubhouse to pack up his belongings and was about to get into his car when Poldberg called him back into his office. Expecting some last-minute details on his long-awaited promotion to The Show, he was totally unprepared for what he was about to hear – the Royals had changed their minds, and reliever Brandon Finnegan was going up instead.

Merrifield struggled the rest of the way. “I ended up not being very mentally tough about it. I turned a good year into just a very average year,” he admits. When he got home, he sat down with his dad.

“I’m just not having a good time, struggling to want to go to the field every day and try to continue chase this,” Merrifield told his father. “And he understood it was sucking the life out of me.”

If anyone would understand, it was Bill. A second-round pick of the then California Angels in 1983, he’d been stuck in their system four years when on Aug. 29, 1987 he was traded to the Pirates along with left-hander Miguel Garcia for veteran second baseman Johnny Ray.

Bill simply had to change dugouts that day as the clubs’ affiliates were playing each other. He crossed over from triple-A Edmonton to triple-A Vancouver, played three games there and then suddenly found himself making three stops en route to Pittsburgh, arrived at Three Rivers Stadium with nothing but Canadian money and needed one of his new teammates to cover the cab fare to the stadium.

Twenty minutes after checking in, he was instructed to take the field for batting practice under the close watch of manager Jim Leyland and GM Syd Thrift, who told him to swing for a variety of different situations. A third baseman, he was told he would start at first, started searching around for cleats and clothes as lefty Bob Kipper introduced him around the clubhouse and then when the game was delayed by rain, he was called into the manager’s office where he figured they’d go over signs and strategies. Instead, he was told to report to instructional league and prove that he could hit for power. His locker had already been packed once he left the meeting.

“I was disappointed, certainly,” says Bill. “But I thought this is a brand new start with a new organization, they’re going to give me every opportunity now because they traded for me. Why else would they trade for me? And it just didn’t work out that way.”

The next spring, Leyland essentially told him the club had no spot for him, he was sent to minor-league camp and was set to begin the season at triple-A Buffalo when he was traded again, this time to Texas. He arrived at triple-A Oklahoma City in time for a pair of warm-up games and in the dugout, met manager Toby Harrah, who looked at him and said, “‘Who are you?’” Bill recalls. “I said, ‘Bill Merrifield, I’m your new player. I just got traded.’ He goes, ‘Well, what position?’ I said, ‘Third base.’ He goes, ‘I’ve got a third baseman and walked away.’”

Eventually he found his way into 90 games before suffering a broken foot, one discovered only after a four-hour post-game bus ride from Des Moines to Omaha, his leg wrapped in ice and elevated the whole way. The next morning he went for X-Rays that revealed the fracture, he took the pictures with him to Rosenblatt Stadium, where the team was working out, walked into the dugout holding up the scans “and I said, ‘Toby, my foot’s broken out. I’m out.’ He looked at me and said, ‘OK.’ And that was the last time I played.”

Years later, after his son won the College World Series for South Carolina with a walk-off single at the very same Rosenblatt Stadium, Bill would think of how that happening at the park his pro career came to an end, “brought it all full circle. It was kind of cool.”

The parallels in their pro ball experiences came in handy as Merrifield weighed his future. His friends were all beginning to build their lives while he felt stuck in neutral, chasing a dream he didn’t seem capable of fulfilling. Bill had been there, too, deciding that it was time to stop dragging wife Kissy all over the place and start their family. But he also wanted his son to be certain.

“He said to me, ‘You know dad, I’m done. I don’t want to keep doing this. It doesn’t seem like anything I do is good enough,’” he recalls. “I just told him, ‘I’m 100 per cent behind you, I will support you whatever you do. I get it. But the one thing you have to consider is that once you take your cleats off, you’re done, you can’t put them back on again.’”

The finality of the decision really resonated.

“He was like, ‘Look, I get it. I was there. I quit right when I was on the cusp. And I don’t regret it because I didn’t like it. But if you want a chance to know what that big-league life is like, stick it out,’” says Merrifield. “He told me to do what I wanted to do, that if I don’t like it, don’t play. But to know that whenever I’m done, I’m done, that you can’t really come back and try again if you changed your mind.”

After wrestling with the call, he decided to give it one more year. They hatched a workout plan that helped him add about 20 pounds of muscle. The extra strength meant he hit the ball a little harder and the Royals noticed at spring training in 2016, when he was again the final cut of camp.

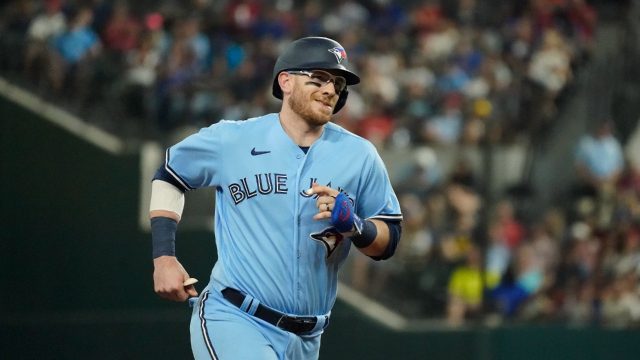

This time he did earn a call-up, debuting May 8 in the second game of a doubleheader against the Boston Red Sox with a base hit off David Price. He’d later be demoted during a brief dry spell but played in 81 games that year, again didn’t make the team out of camp in 2017, but was recalled about two weeks into the season and was up to stay, eventually becoming an all-star in 2019 and 2021, and now a key contributor for the Blue Jays.

“I was fortunate that my parents were real supportive of me,” says Merrifield. “I got to live at home in the off-season because you’re not making any money in the minors, so I couldn’t afford to live on my own. I didn’t have to get a job in the off-season or anything like that, they kept me going, so I stuck it out.”

The two used to talk hitting after almost every game, but Merrifield is “at the point of my career now that I don’t want to take it home anymore, I’ve done that enough in my life. If I talk to him on the phone, I can feel him wanting to talk about hitting if he feels like I’m struggling. And I’m just like, ‘I don’t want to talk about it anymore.’”

Bill understands that his work on that front is finished, even if it’s sometimes hard to shut off his instincts as coach, and as a dad. “I still watch all his games like I’m coaching third base, I’m cussing and I’m yelling. It’s fun watching your kid do something special at the highest level that they can be.”