When Bob Cole was a boy living in pre-Confederation Newfoundland, he suffered a sports injury that nearly cost him his leg.

He grew up in St. John’s, where his father was the warden of Her Majesty’s Penitentiary, and was an excellent all-around athlete at Bishop Feild School, one of the city’s hallowed halls of learning. Though Canadians would come to know him as the voice of their national game, over the course of his long life Cole would also skip a rink at the Brier, row and serve as a coxswain in the Royal St. John’s Regatta, distinguish himself in football and baseball and hockey, and play a pretty decent game of golf.

But before most of those accomplishments, he hurt his leg playing soccer, and the complications that ensued left him laid up for weeks. Confined to his bed, he listened to hockey on the radio from far-away Maple Leaf Gardens, with cards bearing the faces of his heroes laid out in front of him as though they were on the ice.

The voice he heard was Foster Hewitt’s, who always mentioned the fans in Newfoundland in his famous opening. When he was alone, Cole would mimic Hewitt, calling the games in his style — which was the only style, since he all but invented hockey play-by-play. When he got back to school, Cole would do it again for his pals, recreating the action from Saturday night, much to their delight.

The path from there to Hewitt’s Gardens gondola, to the Montreal Forum, to the Luzhniki Ice Palace and to pretty much everywhere else that big-time hockey is played was unlikely and meandering and helped along by strokes of luck, coincidences, and no small amount of chutzpah.

But at the core of it was his talent. Bob Cole, like his mentor Hewitt and his friend Danny Gallivan, possessed the innate ability to sound like hockey.

Before he wound up as the primary voice of Hockey Night in Canada, Cole had already lived several lives.

Seeking adventure as a teenager, he signed on as a bell boy and steward and sailed to New York and then on to the Caribbean. As a young Air Cadet, he spent a summer learning to fly in Nova Scotia. On his first solo flight, he was forced to put his failing Piper Cub down for a crash landing, then spent a long cold night in the woods waiting to be rescued.

Back home in St. John’s, he applied for a job doing late-night radio, and that led to a chance to broadcast local hockey games from the old Memorial Stadium.

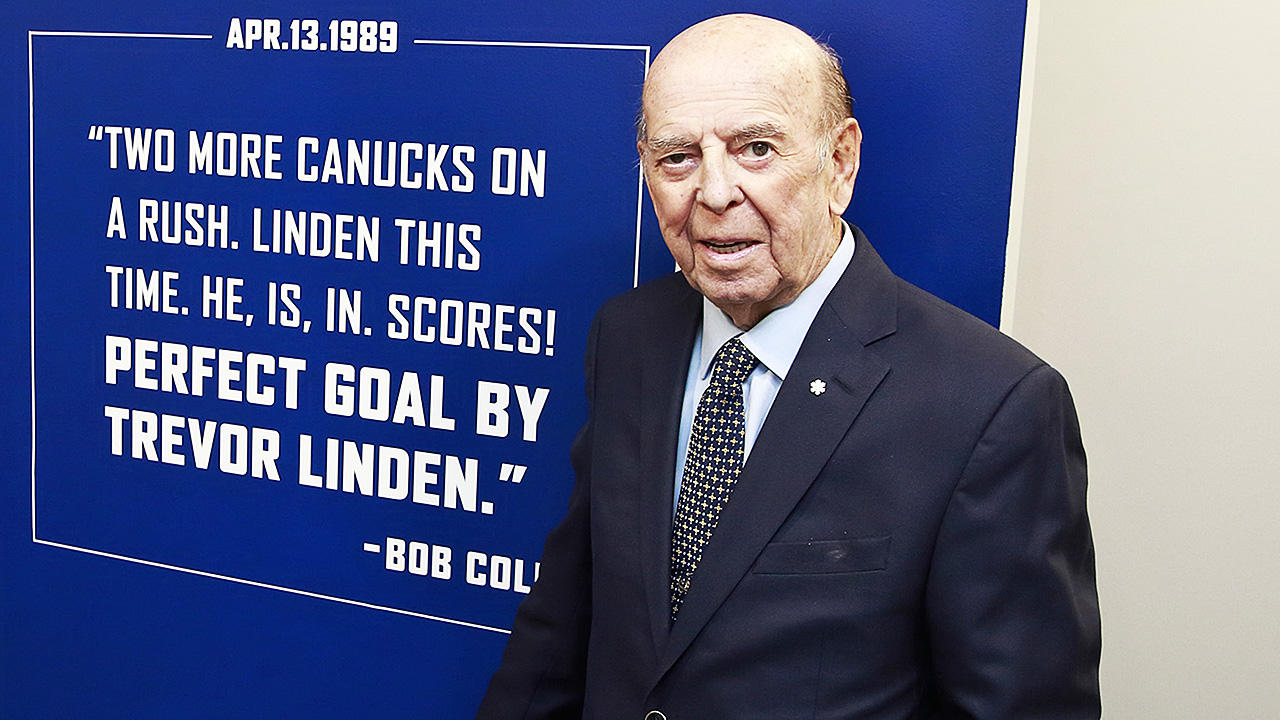

But it’s likely no one would have known Bob Cole outside of Newfoundland but for his own moxie. During a stop on a long, windy road trip to New York with some pals (he talked his way into a Yankee Stadium press pass, and interviewed and took a picture of Mickey Mantle on the field), he walked into the offices of Hewitt’s Toronto radio station, CKFH, with an audition tape in hand. The plan was to drop it off at reception. Instead, Hewitt invited him in. They talked about the art of calling hockey games, and it was there that Cole first heard Hewitt’s mantra: It was all about “feel and flow,” he was told. You had to capture the excitement and movement of the game with your voice, and deliver it to the listener.

Cole never forgot that, and you could argue that he became the master of the art, anticipating the play in a lightning-fast game, channeling the building excitement through his voice, and then delivering in those big moments, brilliantly. He made even the dullest game worth watching.

By the time he got his big break in 1969, calling what turned out to be Jean Beliveau’s final game as the Montreal Canadiens won the Stanley Cup, Cole had already established himself as a broadcaster at home. He was the first television news reader in Newfoundland, and as the host of the local version of the high school quiz show Reach For The Top, which was enormously popular, he was one of the most recognized faces in the province.

Three years after his NHL debut, Cole provided the radio play-by-play for the Summit Series in 1972. His call of Paul Henderson’s iconic goal, though not as well known as Hewitt’s on television, is a masterpiece. He returned to the USSR two years later when a group of WHA all-stars faced off against the Big Red Machine.

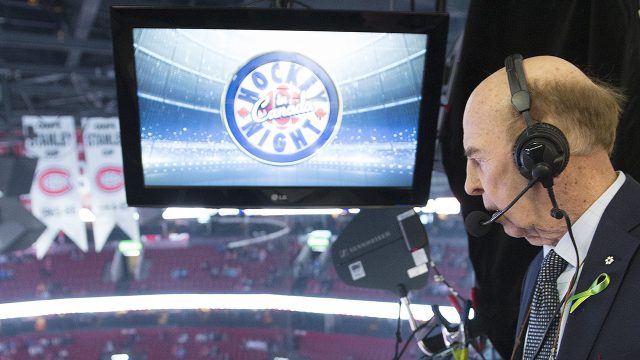

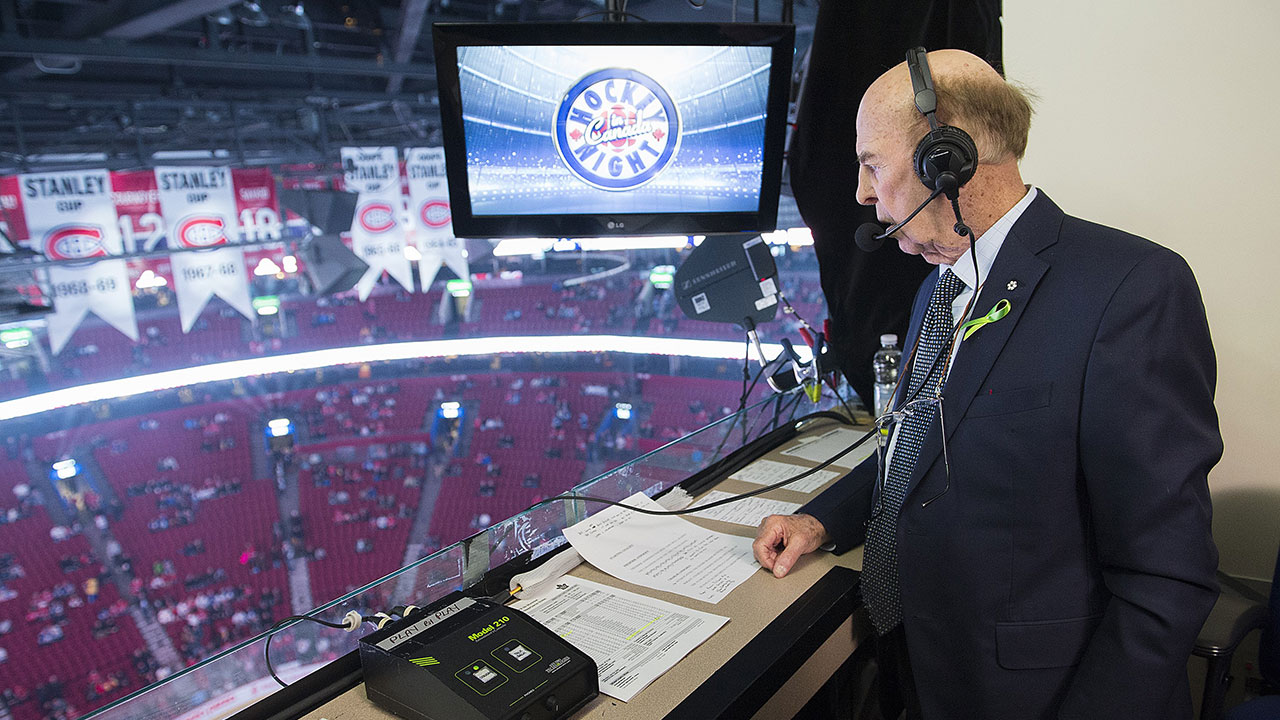

By then, he had taken the place of Bill Hewitt, Foster’s son, on Hockey Night in Canada broadcasts from Toronto. He provided the soundtrack for the dynasty years of the New York Islanders and Edmonton Oilers, for the last two Montreal Stanley Cup victories, and for the Maple Leafs’ early-’90s renaissance. Be it Wayne Gretzky, or Mario Lemieux, or Joe Sakic in Salt Lake City in 2002, it is impossible to think back to some of the most memorable hockey moments of our lifetimes, and not hear them narrated by Bob Cole.

He certainly had his quirks. He didn’t like to be touched. He unbuttoned his pants when he called a game. His partners in the broadcast booth knew that when Cole gave them the “Heisman” straight arm, it was time to be quiet, and let him finish. For a time he ran a fish-processing plant during summers back home. He didn’t enjoy it when others treated him to their Bob Cole impressions. He drank Captain Morgan rum (and no other rum) and Coke (and no other cola), and would go to extraordinary lengths to make sure both were available — even in the Soviet Union in 1972 and 1974, and in his Pepsi-centric home province. Those in the business also tell tales about his remarkable physical strength, which came as a surprise to many, and served him well even in his later years.

And, of course, Cole never left Newfoundland, even though it meant at least two three-hour flights every week during the season to get to work and back, most of those in the dead of winter.

During his final seasons as a broadcaster, after almost half a century calling NHL games, Cole still insisted on listening to air checks of his work. He wanted to pick up any mistakes, and to make sure that he was still delivering the “feel and flow” of the game as Hewitt had described so many years before — that he wasn’t losing his touch.

To his ears, and to the ears of so many of us, he never did.

Stephen Brunt was proud to collaborate with Bob Cole on his autobiography, Now I’m Catching On: My Life On and Off the Air.