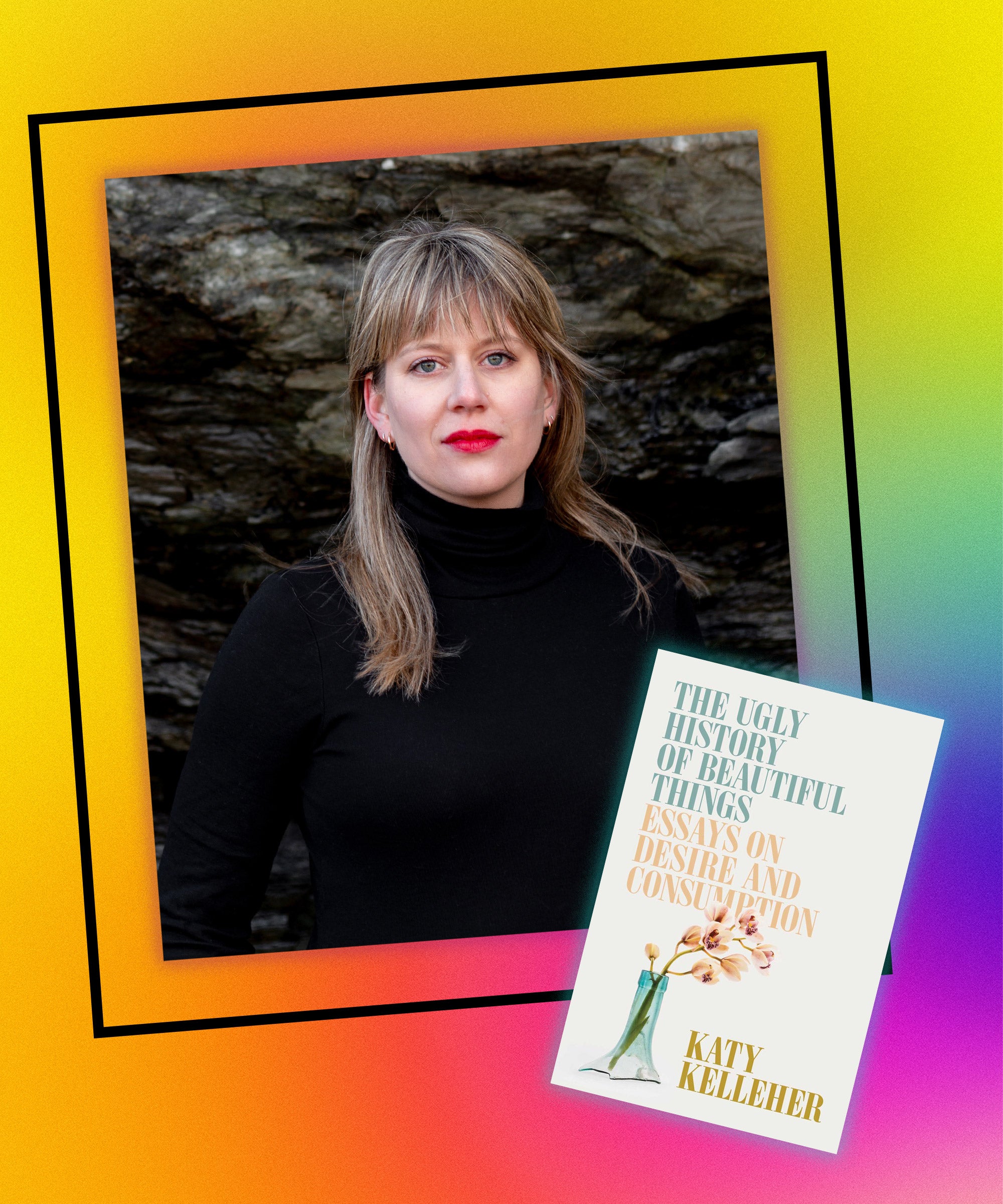

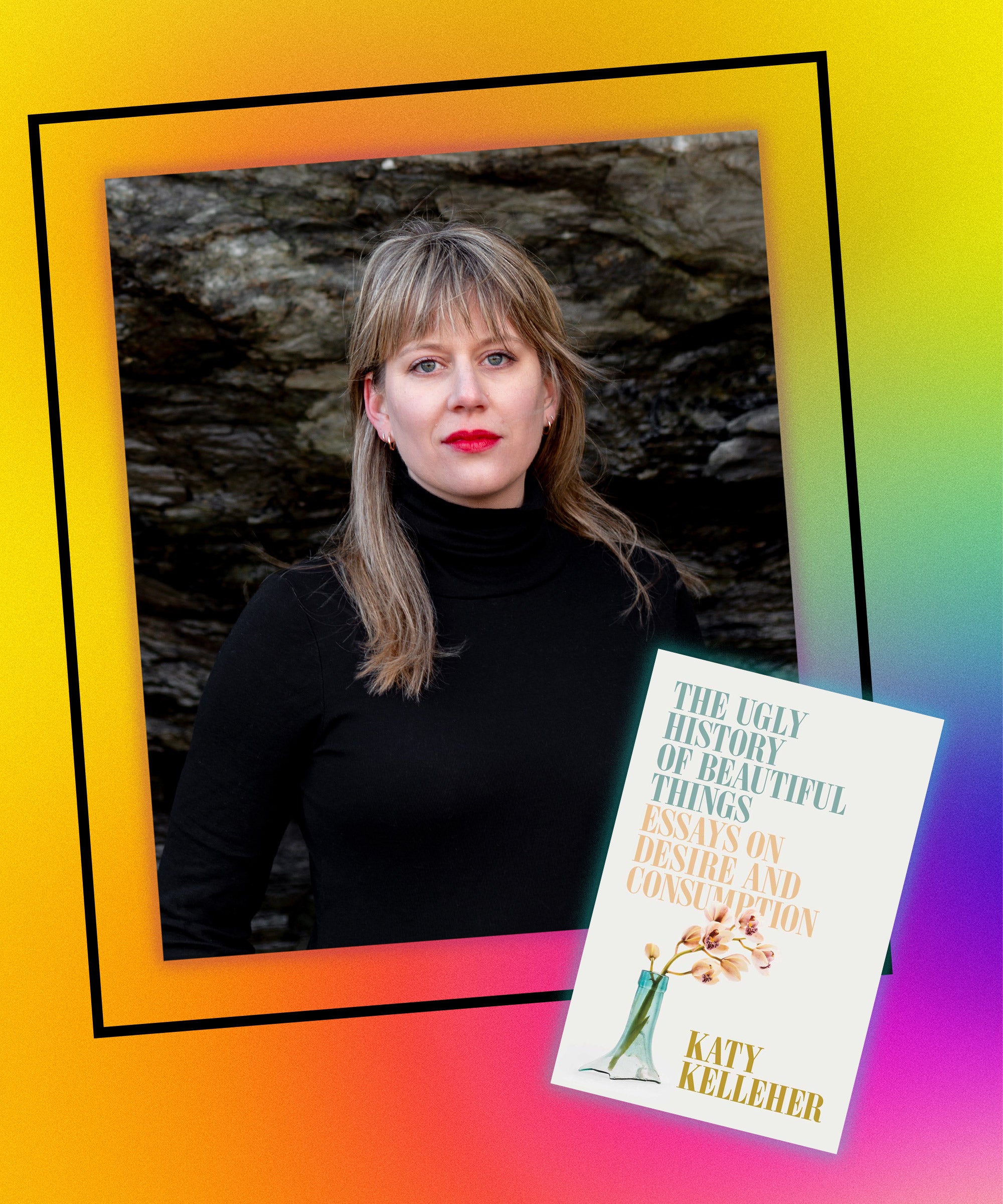

Katy Kelleher is an art, design, nature, and science writer living in the woods of Maine. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, The Guardian, American Scholar, and Town & Country. Her most recent book, The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Essays on Desire and Consumption, is available now.

I never wanted a diamond engagement ring, at least that’s what I said. “I’d prefer something more unique,” I told my friends, “I want something colorful. I can’t stomach having a conflict jewel. And I don’t need anyone to spend that much money on me.” These things were all halfway true. I didn’t think I wanted a diamond for personal aesthetic and ethical reasons. I knew my boyfriend couldn’t afford one, not if we were also going to have a wedding or maybe someday buy a house or even, at the time, continue paying our rent. Perhaps that’s the deepest truth: I didn’t want one because I couldn’t want one.

I did, however, want to get married to my partner, my boyfriend, my cancer-surviving, ex-pharma scientist guy who left research to become a high school teacher and was, genuinely, the most moral person I knew. He was also the most frugal man I’d ever dated and a pretty straightforward person, to boot. I said I didn’t want a diamond, so he wasn’t going to get me one. It was as simple as that.

As I learned from writing The Ugly History of Beautiful Things, engagement rings are a tricky symbol to trace, partially because there’s so much misinformation out there. When it comes to romance, we all want to be fooled, just a little, so it makes sense that some myths get repeated time and again until they sound true.

For instance, you may have heard that the tradition of wearing a ring on the fourth finger of the left hand dates back to the ancient Egyptians, whose meticulous study of cadavers revealed the presence of a vein that flowed straight from that digit to the beating center of the torso. Hand to heart, what a lovely idea. Yet not only is there no Vena amoris (as it was dubbed), but there’s also little evidence to support the idea of ancients routinely wearing engagement rings. When they did exchange round trinkets, they were often woven out of reeds, not forged of gold. And while the Greeks and Romans took to wearing matrimonial rings several centuries later, these weren’t necessarily symbols of love. Just as often, they represented binding and belonging — i.e. ownership. Wives wore them to symbolize their obedience and fealty to their husbands, and men wore them to honor their superiors. I suppose these rings all signaled a pledge of sorts, but it’s hard to square these practices with our contemporary notions of forever stones and golden anniversaries.

I’m not trying to suggest that romantic partnership and lifelong love didn’t exist before modern marketing. Humans love, it’s one of the best things we do. But too often, how we show our love is socially prescribed, manufactured by corporations, and comes at great expense.

I’m not trying to suggest that romantic partnership and lifelong love didn’t exist before modern marketing. Humans love, it’s one of the best things we do. But too often, how we show our love is socially prescribed, manufactured by corporations, and comes at great expense.

Consider the diamond. Many people believe diamonds are expensive because they are rare, but this isn’t true. Not only do Kimberlite pipes (cone-shaped, high-pressure eruptions of magma that often contain diamonds) exist in every continent on Earth but we can — and do! — make diamonds in a lab. Then, the reason that diamonds are valuable is not because they are scarce but because we perceive them to be valuable.

We can thank De Beers for this. After diamonds briefly fell out of fashion in the 1930s, they became the go-to stone for engagements in the 1940s after copywriter Mary Frances Gerety came up with the four-word slogan: “A Diamond Is Forever.” Not only does this phrase remind consumers of the diamond’s most notable property (its metal-cutting hardness) but, by linking the product with the concept of endlessness, De Beers placed their stone on the same symbolic plane as the eternal circle itself. It became an emblem of commitment.

Another relevant example of modern marketing comes from early 20th-century America, when the platinum craze hit high society. Although initially considered an inferior metal by the gold-obsessed Spanish conquistadors, who seized South American mines from the Indigenous population, in the 18th century, platinum rose to prominence as the “eighth metal” thanks to the efforts of Parisian jeweler Louis Cartier. By pairing the pearly, lustrous metal with diamonds, Cartier created a new kind of glamour, one that was comparatively colorless and thus considered less “vulgar” than traditional gold and gemstones, according to Hugh Aldersey-Willimas, author of Periodic Tales: a Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to Zinc: “Cartier’s innovation unleashed a fashion for platinum in the grandest jewelry.”

The newly pricey metal was further popularized by the Duchess of Windsor, a glamorous, twice-divorced American socialite by the name of Wallis Simpson. In addition to being a successful social climber, she was also an incorrigible snob; Simpson once said that “any fool would know” to wear platinum with their evening wear. But like Simpson, whose reputation as a suspected Nazi sympathizer saw her popularity fall vastly as the decades wore on, platinum also disappeared from the public eye. In large part this had to do with the metal being heavily rationed by the Allied powers during the Second World War for it proved quite useful in the manufacture of explosives.

Diamonds aren’t made any more or less beautiful because of their cultural associations, but I do find it fascinating how easily we, as consumers, can be manipulated into spending more money than is wise on objects that we can hardly be said to need. Me included.

When the time came, Garrett proposed without a diamond, and, at first, I didn’t mind at all. But then, one day, not long after I became engaged, my friend Sophie grasped my hands over dinner and took off my sterling silver cuff bracelet, the one I always wear, even when swimming or showering, the one that was a gift from my mother and feels like a part of my body. Slowly, she turned it over in her hands. “I love seeing this,” she said. “It’s so you.” In turn, I tried on jewelry she always wore, feeling the weight of her beaded yellow gold wedding band, her inherited little diamond. In that moment, sitting in a pizza shop, I realized something. I, too, wanted to wear my love on my hands.

Later that week, I told Garrett the truth. I wanted a wedding band that I would never remove, something precious and pretty, something delicate and so me. It didn’t happen overnight, but together, we found the right ring. As I type this, I can look down and see the cold sparkle of recycled salt-and-pepper diamond chips, embedded in a thin band of recycled white gold. Although it was a budget option from a small designer, and although it is greener than some rings, it’s not an entirely harmless choice. All mining has its costs. But still, I’m proud of what it means. It signifies a partnership with a person who supports and respects me, someone who loves my writing, laughs at my jokes, and plans to be with me forever.

While this should be enough, I have to admit: I’ve recently found myself obsessed lately with Victorian rings. Late at night, when I can’t sleep, I scroll through vintage jewelers and consider the options. My desire is inspired, at least in part, by the historical research I’ve been doing for my book. It’s not that I want to emulate Queen Victoria, but I find her story fascinating, and her style even more so. For much of her life, Victoria wore an 18-karat gold serpent ring, set with rubies (for the eyes), diamonds (for the mouth), and a large emerald (at the crown of the snake’s head). This was her engagement ring, a gift from her beloved Albert. After Victoria was spotted wearing it, thousands of similar baubles were sold at jewelry shops throughout Europe and America. Despite the animal’s association with temptation and treachery, these rings remain popular even now, symbols of unending love. As for the original ring, it appears to have been buried with the queen, an everlasting tribute to her one great love.

I don’t need one, of course, but maybe, one day, I’ll ask my husband to get me one for my birthday.

Katy Kelleher‘s The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Essays on Desire and Consumption is out now.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

7 Engagement Ring Trends Taking Over 2023