In the spring of 1974, one conversation dominated the streets of Crawfordville, Ga. The town wasn’t blatantly segregated like many areas in the South, but pass by one corner and you may see a group of older white men sitting together. Just down the road you might see a gathering of older Black men. Still, though, each group would likely be covering the same ground — having that discussion.

Bob Kendrick was almost 12 years old in April of that year and vividly remembers the ongoing debate in his hometown.

“People were so divided about the possibility of this Black man in the South about to break this white man’s record that everybody thought would never be broken,” Kendrick, the president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, told me during an interview in 2019.

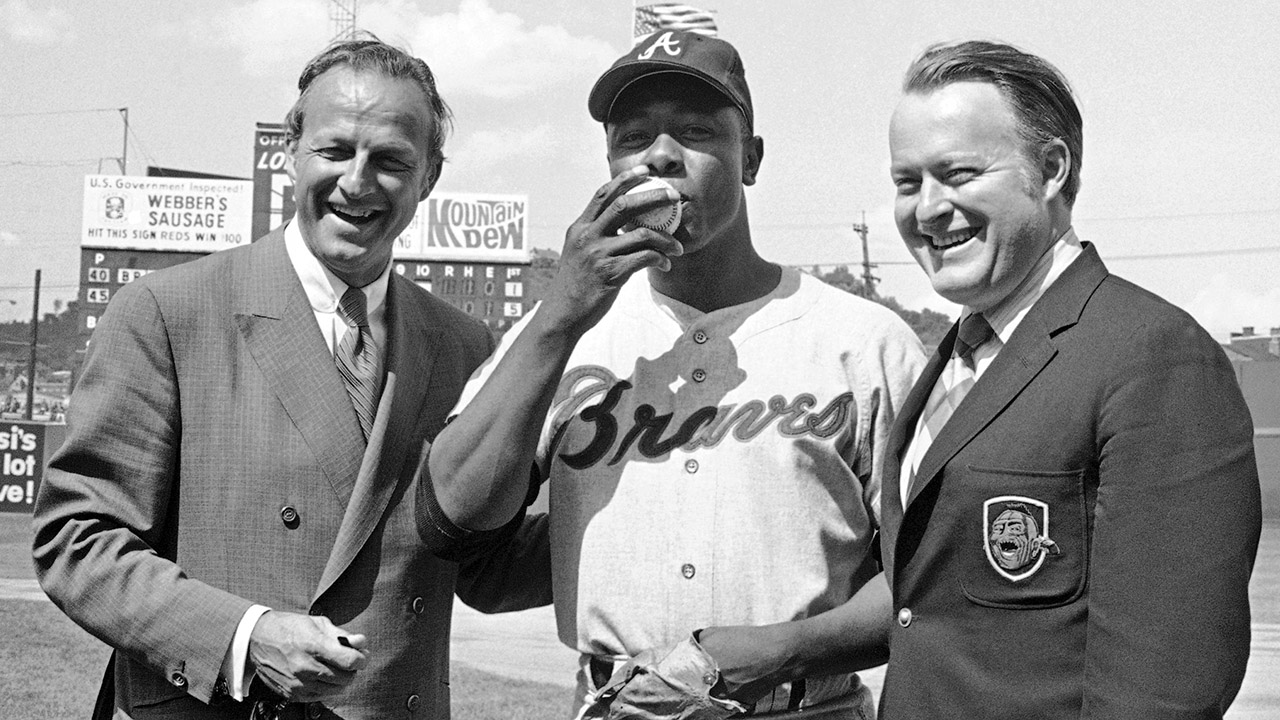

He’s of course talking about Henry “Hank” Aaron’s pursuit of Babe Ruth’s fabled record, which he surpassed on April 8, 1974, to become baseball’s home run king.

Aaron, who stands as one of the sport’s most cherished and storied players, passed away Friday at the age of 86. He was famously given the nickname Hammerin’ Hank for his ability to consistently make hard contact, but the lessons Aaron left behind to Kendrick and countless others extended much further than just the ballpark.

Kendrick was a mere child when Aaron chased Ruth’s record — he observed what was happening, but it wasn’t until years later that he fully grasped the hardship his favourite player endured.

With each home run bringing Aaron closer to history, the racist death threats intensified. He received hate-filled letters from across the country; sent his children to private school; hired a bodyguard; and stayed in a different hotel than the rest of his team.

On some nights, Aaron even slept in the ballpark by himself. All because people were mad he was going to eclipse a record.

“You don’t really understand it,” said Kendrick. “But what I admired as I got older was the grace, class, dignity with which he handled that set of circumstances. You gotta think that would have broke a lot of people. It would have broke them down and, somehow, he was able to persevere and then rise above the hate.

“To me, those are the qualities that are so exemplary.”

Aaron’s 715th homer, which toppled Ruth, was the highlight of a career filled with enough achievements to fill a textbook. The Mobile, Ala., native retired after the 1976 season as the all-time home run king with 755 long balls, a mark that was broken by Barry Bonds in 2007.

Hank Aaron. Legendary figure, and a hero to so many.

( @espn)

— Baseball America (@BaseballAmerica) January 22, 2021

Over his 23-year MLB career with the Milwaukee Braves, Atlanta Braves and Milwaukee Brewers, Aaron won two batting titles, led the league in homers four times and secured an all-star selection in 21 straight seasons. He collected his only MVP award in 1957, the same year he won his lone World Series ring.

His 2,297 RBIs are the most ever, as are his total bases (6,856). Meanwhile, his 3,771 career hits are third in MLB history. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982 and worked for decades in the Braves front office following the end of his playing days.

Aaron made many friends during his lifetime in baseball. One of them was Cito Gaston, a former Braves teammate and roomie. Though, as Gaston has said in the past, Aaron was almost a father figure as much as he was a good friend.

“What’s a sad story is I was so amazed and just absolutely crazy about being his roommate, because he’s my childhood hero,” Gaston, former manager of the Toronto Blue Jays, told me in 2019. “So I never bothered him about hitting, which was just the absolutely biggest mistake I ever made in my life.”

Gaston, an outfielder who played in parts of 11 big-league seasons, was called up to the majors for the first time in 1967 and was assigned to room with Aaron.

“If I had asked him (about hitting), he would have been happy to talk about that,” he says. “It took me six more years to learn [how to hit]. I wasted my time there.

“I tell you what he did (teach) me,” adds Gaston. “He (taught) me how to stand on my own two feet. (Taught) me that whatever you do today, don’t bring it back tomorrow, because you have to keep going. You can’t live on what happened yesterday.

“He also taught me how to tie a tie.”

Kendrick also had the chance to spend time with his boyhood idol, at one point guiding him on a tour through the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Kendrick’s work at the Kansas City institution was informed in no small way by what he saw Aaron live through in the ’70s.

“More times than not, we celebrate the people who cross over the bridge,” says Kendrick. “But here at the Negro Leagues Museum, we celebrate the people who built the bridge that allowed the Mookie Betts and the CC Sabathias and the Adam Joneses and the Ozzie Smiths and all the great, Black stars to make a living in this game crossing over the bridge.

“We shouldn’t forget the bridge builders.”

Aaron, with a mighty bat acting as his hammer, was one such craftsman. And for that, he’ll never be forgotten.