Film industries around the world exist independently of Hollywood, and Russian producers might just be about to strike gold

Over the past year, many Western companies have left Russia. This hasn’t just affected the economy, it has also altered the cultural landscape. The film industry is no exception. Without Western premieres and streaming services, the country is reconsidering its approach to the film business.

Russia has many examples to look to for inspiration. In many places, national cinema retains a leading position at the box office. It is both financially successful and independent of Hollywood, in the likes of France and India, to name just two examples. Different countries have built their film industries in different ways. Some have focused on domestic audiences, while others fostered a state-supported concept aimed at both local and foreign viewers. Many have developed under strict censorship and invented a metaphorical film language that resonated with international film festival audiences.

So how did these countries escape the grip of Hollywood? And how far has Russia traveled in this direction over the past year?

What happened?

After February 24, last year, many Western production companies closed their Russian offices and terminated contracts with local studios. Paramount Pictures and Warner Bros., Netflix and Amazon Prime, Marvel and Disney all stopped releasing films in Russia or suspended access to their streaming platforms.

This decision impacted both the film industry and ordinary viewers. Joint projects with Netflix have been paused indefinitely. The global streaming platform previously purchased Russian series like “The Epidemic” and “The Method” and planned to produce its own original content in Russian. The year’s highest-grossing movies globally – “The Batman” and “Top Gun: Maverick” have become unavailable in Russia. Legally, at least.

Along with US motion picture companies, several West European studios also left Russia. However, within a year it became evident that they are more dependent on the Russian market than their US counterparts. One example is the French cinema company Pathé which announced in early December that it would return.

For the past decade, Russia has been an active part of the international film market. While in the 1990s and 2000s its cinema was primarily associated with film festivals, in the 2010s a homegrown blockbuster market emerged. Russian directors, such as Kantemir Balagov and Ilya Naishuller, took part in big-budget international movie projects.

Russian movies and series found an audience. For example, “The Epidemic” made Netflix’s most-viewed list.

Political differences cast Russian cinema into a new reality. The industry will now have to revisit traditional production and distribution methods and explore how they work beyond Hollywood.

Why does Hollywood dominate the world’s cinema?

Hollywood is a unique industry. Its modern movies are specifically tailored to international audiences. Their goal is to encompass the widest possible number of viewers.

There are a variety of reasons and viewpoints on why Hollywood dominates the global film market. Among other factors, this is linked to a greater urban population in the US, as opposed to other countries. In the US, the domestic market proved to be so large that movies made returns at home and were then exported abroad to compete with local film industries. Such a strategy eliminates risks, since, even in case of failure, the production can’t suffer a significant financial loss. Moreover, the growth of the US economy in the post-WWII era contributed to the strengthening of the film industry, especially against the background of the economic damage inflicted on Europe.

However, even Hollywood hasn’t been able to take over all markets. It is much less popular in countries with protectionist laws in place, such as France. The share of American movies is also smaller in regions with significant cultural differences like India, China, and Africa.

© Getty Images/Eloi_Omella

China. Dictates its own rules to Hollywood

Currently, China has one of the largest film industries in the world. But just a few decades ago, its cinema was largely provincial and unable to win over the hearts of local audiences. The primary reasons for the progress have been surging development and new economic and technological opportunities that allowed the Chinese film industry to directly compete with big-budget Hollywood blockbusters.

In 2007, 14 of the 25 top movies at the Chinese box-office were shot in the United States. In 2019, that number dropped to 8. All remaining 17 movies were Chinese. In addition, box office receipts have grown from $800 million to $9.2 billion in ten years. The coronavirus pandemic dealt a significant blow to the industry, but over the past two years, it has almost recovered, and in 2023, will likely break previous records.

Having acquired an independent position in cinematography, China has been able to dictate its own rules to Hollywood. Due to its volume, the Chinese market has become so important for Hollywood that US film companies are ready to adapt to the requirements of local partners, especially regarding movies targeted at Asian audiences.

Moreover, Chinese censorship is unique because the content censored during post-production doesn’t just affect the copy meant for Chinese audiences – it influences the version shown to the whole world. For example, in 2020, at the insistence of the Disney office in China, the kissing scene between the main character and her beloved was cut from the movie “Mulan”. This decision was made so that Chinese viewers would not consider this plot twist disrespectful to the original myth of Hua Mulan.

Political factors are the most common reasons behind the censorship or even the ban of Hollywood movies in China. Movies directly or indirectly referring to the three “Ts” – Tibet, Taiwan, Tiananmen – will definitely not be shown in China. In 2016, in order to placate Chinese audiences, the Tibetan ethnicity of one of the characters in the Marvel film “Doctor Strange” was changed. Commenting on the decision, screenwriter C. Robert Cargill said that following the comics to the letter would “risk alienating one billion people”. China doesn’t just fail to recognize the independence of Tibet but denies the very existence of Tibetan identity. The failing career of actor Richard Gere, who was a friend of the Dalai Lama and an active supporter of Tibetan independence, is also linked to Chinese censorship. Moreover, Gere has long been persona non grata at the Academy Awards after he publicly criticized China’s policy at the event in 1993.

© Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Iran. Triumphs at film festivals despite isolation

In 2022, Russia experienced fresh interest in Iranian cinema. Once considered exclusively a film festival phenomenon, today it’s emerging into an industry that may help Russia understand its own near future. Some officials see Iran as an alternative to Hollywood. State Duma deputy Sergey Solovyov suggested that in Iranian cinema, Russian audiences will find “long-missed stories”. In June 2022, the production of the first joint Russian-Iranian film was announced.

The social problems of ordinary people lie at the heart of Iranian cinema. Their stories mix the everyday and the metaphorical. This intersection of social issues and symbolic film language is tied to strict state and religious censorship. Iranian artists often have to find non-trivial ways of implementing their ideas, and this applies to the movie industry as well.

For example, director Jafar Panahi was sentenced to 10 years in prison for participating in anti-government protests against official election results in 2009. In addition to the imprisonment, which was reduced to house arrest, he was forbidden to make films and give interviews for a period of 20 years. But despite this, over the past 12 years Panahi managed to shoot five movies and send them to international film festivals. Three of them were created with a minimal budget and shot in one location (apartment, house, car). Making a strong political statement in regard to modern Iran, these movies are also valuable from an artistic point of view.

There’s a paradoxical link between censorship and the development of cinematic language. Having no chance to state things directly, the authors find ways to enrich their movies with symbols and metaphors, while trying to keep the balance between politics and capturing the interest of the audience. As an example, we can take the many movies on the subject of the Iran-Iraq war. Iranian directors manage to shoot unique war films without showing the bloodshed and violence on screen.

Iranian cinema is prized all over the world. In addition to awards at the Cannes Film Festival and the Berlin Film Festival, Iranian releases have won two Academy Awards for “Best foreign language film”. These were two of Asghar Farhadi’s movies, produced five years apart: “A Separation” and “The Salesman”. They are based on everyday subjects with universal themes.

© Robyn BECK / AFP

France. Makes its own movies at the expense of others

The French film industry is the oldest in the world and, based on the number of movies produced each year, the most successful in Europe. It is also known for its successful protectionist policies, a model that Russia’s former Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky has proposed to emulate. The policy is rooted in the interwar period (1918-1939). At that time, Hollywood’s expansion into war-weakened European markets called into question the existence of national film industries. Due to minimal cultural, language, and economic barriers, Great Britain was hit the hardest. In France, the share of French films fell to a mere 10%.

In 1928, the government approved quotas for foreign cinema. The introduction of protectionist measures coincided with the birth of “talkies.” A year earlier, “The Jazz Singer”, the first sound film in the history of cinema, was released in the US. When the characters started speaking, the number of foreign movies at the French box office naturally decreased because of the language barrier.

The policy fulfilled its mission and helped save French cinema. Following WWII, mutual agreements were concluded between Paris and the US, and quotas were replaced by a system of support for the local film industry. Since 1948, about 10% of the cost of each ticket has gone to the Centre National du Cinéma (CNC). These funds go into supporting domestic output, as well as building and modernizing movie theaters.

Television companies, internet providers, and video producers also contribute a percentage from sales to the CNC. The amount depends on several factors such as whether the organization is state or individually owned, how large it is, and the kinds of products it sells. For example, DVD and Blu-Ray movies are taxed at 2%, while pornography is taxed at 10%.

Unlike Russia, the film industry in France doesn’t receive direct state funding. This is replaced by a complex system that collects and distributes taxes according to the needs of the industry. However, as film critic and Cannes Film Festival correspondent on former USSR countries Joel Chapron writes, the money allocated by the CNC constitutes less than 10% of the total budget of the motion picture. Another 25% is provided by French television channels, which are legally required to invest in film production. According to Chapron, nearly half of all French movies are co-productions “made in three, four, or even seven countries”.

France is one of the few places in the world where US movies make up less than half of the market. Local cinema constitutes 35%-45% of the French film market, and Hollywood makes up 45% according to 2014 statistics. Incidentally, France became the main foreign market for Russian cinema in the first half of 2022. In 2021, the war drama “Persian Lessons” became the highest-grossing Russian movie abroad.

The protection of national interests does not interfere with French cosmopolitanism. As the birthplace of cinema, France embraces representatives of different nationalities and cultures. Thus, the Spaniard Luis Bunuel, the Austrian Michael Haneke, and the Poles Roman Polanski and Krzysztof Kieslowski shot some of their best films in French, and Argentinian-born filmmaker Gaspar Noe is considered an icon of modern French cinema.

India. Many competing markets in one country

Movies came to India quite early, just a year after the Paris premiere of the Lumiere brothers’ “Arrival of a Train”. Today, India is the world’s largest producer of films. The country has many independent companies that produce movies for the local population. This is due to the large variety of languages spoken by the Indians.

For most foreign viewers, Indian cinema is directly associated with Bollywood. It’s indeed one of the centers of the industry but is in no way inferior to other, less popular “-woods”. In addition to Bollywood, there is Tollywood (Hyderabad), Kollywood (Chennai), Mollywood (films in Malayalam) and others. India even has its own Hollywood (Gujarat).

Bollywood has been badly hit by the coronavirus pandemic. Among other things, this proved that the old ways of making movies aren’t effective anymore. The audience isn’t satisfied with a few popular actors and familiar narratives that aren’t rooted in Indian culture. Critics of modern Bollywood warn that the industry is losing its identity and is ignoring India’s social, cultural, and political characteristics.

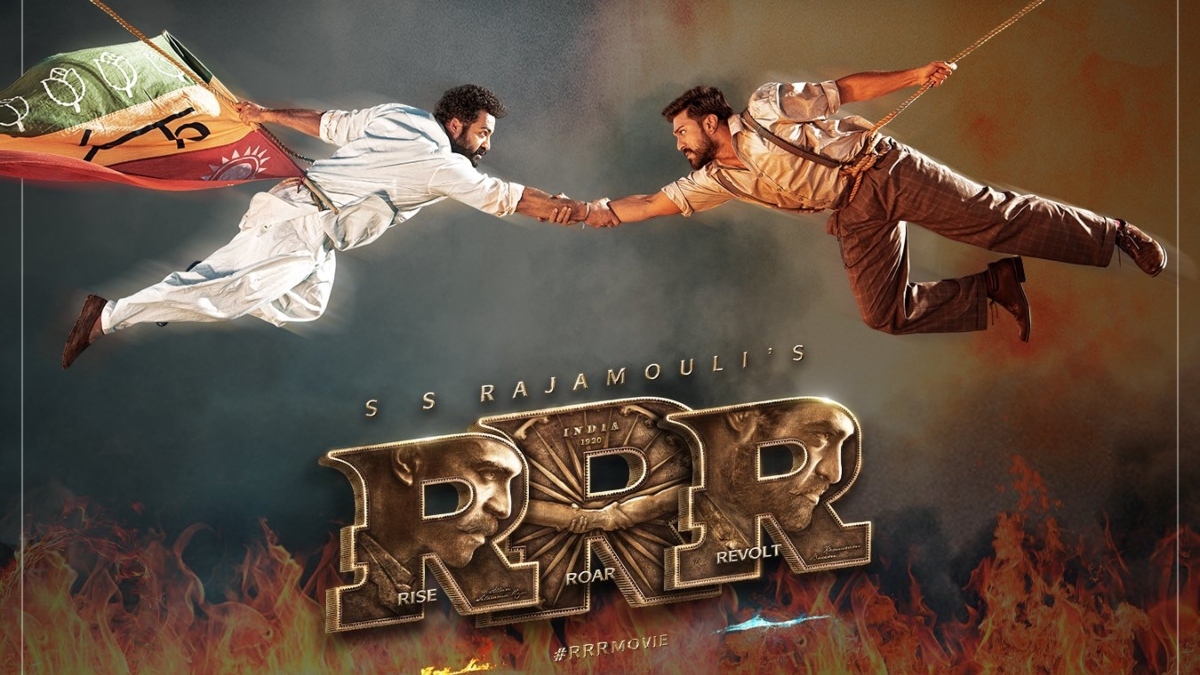

However, in recent years, many motion picture studios have emerged in South India. Compared to the Westernized Bollywood that ignores India’s regional identity, their movies are closer to the people. One example is the action movie RRR about the fight for the independence of India. It grossed $160 million internationally and became the third highest-earning Indian movie. Local audiences prefer South Indian motion pictures. A study by the Confederation of Indian Industry showed that in 2021, 62% of total box office receipts came from films produced there.

© DVV Entertainment

Worldwide, Indian cinema is most popular in Asian countries. The country’s traditional values – prioritizing family and respect for elders – relate to Asian audiences. At the same time, Indian cinema is also undergoing major changes and is turning to previously taboo subjects, like same-sex relationships. Modern Indian cinema carefully and respectfully explores phenomena beyond traditional Hindu morality.

Nigeria. Thousands of movies for DVD and VHS

Nigerian cinema is practically unknown abroad. However, the country is second only to India in the number of movies produced annually, which puts it ahead of the US. The film industry has helped Nigeria develop the strongest economy on the African continent. Additionally, cinematography is Nigeria’s second largest economic sector, after agriculture.

The Nigerian film industry has been nicknamed Nollywood, by The New York Times.

Many Nigerians want the term dropped, since it was thought up by an American, and they see it as a concealed form of imperialism. Moreover, they consider that “Nollywood” discredits the African identity, because it implies that Nigerian directors are inferior to Hollywood. Nearly 15 years later, the same New York Times journalist cites both African researchers and ordinary people, all of whom agree that Caucasians cannot fully appreciate Nollywood cinema. Its traditional themes like witchcraft don’t typically resonate with Western or Asian audiences.

In the 2000s, the budget of a Nigerian movie could range from $1,000 to $15,000. Sometimes filming would stop due to a power outage or the threat of terrorists nearby. These movies were produced in just a few days and were immediately distributed on video. In the West, Nollywood is mainly known for outdated special effects. Yet despite the low quality of these films, production was quite profitable since the meager budgets were easily compensated through the sale of VHS with more left to invest into new content.

To estimate the scale of the endless stream of movies in a country where in 2020, only a third of the population used the internet, we can take a look at the filmography of one of Nollywood’s directors. Lancelot Oduwa Imasuen’s IMDB.com profile states that he directed 112 movies. However, the director himself says that in over 20 years, he has shot somewhere between 150-200 movies.

The number of annually produced flicks peaked in 2008 and since then has declined. But for the industry, this indicates growth. It is no longer possible for one person to juggle the roles of director, operator, and composer. Nigerian cinema is becoming more professional and is steadily moving away from the technical inconsistencies of the 1990s and 2000s.

© CRISTINA ALDEHUELA / AFP

However, distribution is still a major challenge for Nollywood. For many years, the movies came out on DVD and VHS and were sold at local markets. Most of the copies were unlicensed. For a long time, this didn’t stop the creators from making money, since the initial investments were trivial.

Western distribution methods are only starting to become popular in Nigeria. In 2021, the country had only 68 movie theaters with a population of over 200 million people. Some streaming platforms, including Netflix, have also become available in Africa. The number of subscribers grows every year.

South Korea. A fierce and successful struggle

In the 21st century, South Korean cinema stopped being a film festival phenomenon and became mainstream, even in the West. The result of this long journey was the triumphs of Bong Joon-ho’s film “Parasite”. It received the Gold Palm Branch of the Cannes Film Festival, won several Academy Awards in key categories including “Best director” and “Best film”, and became an international sensation gathering enthusiastic reviews from critics and audiences alike. The South Korean boom broke out once again after the release of “Squid Game” on Netflix, where it quickly became the top series.

Until recent times, the history of South Korean cinema was littered with failures. For many years, Korea was in a politically subordinate position, which reflected its cinematography. Cinema was a latecomer, and Japanese authorities used it for propaganda purposes. For example, only several “harmless” genres were allowed: costume dramas, melodramas, and propaganda films glorifying Japan. This policy didn’t contribute to the development of viewers’ sympathies.

A former civil servant, Kim Dong-ho, took many measures intended to help Korean cinema. Foreign movies were limited, and each Korean film was shown for nearly half a year. In the 1980s, Koreans weren’t interested in locally produced movies, preferring American titles. However, there were several known instances where nationalists sabotaged screenings of Hollywood films – such as the erotic thriller “Fatal Attraction,” where they planted non-venomous snakes in the hall. A year later, when “Rain Man” was released, venomous snakes were used.

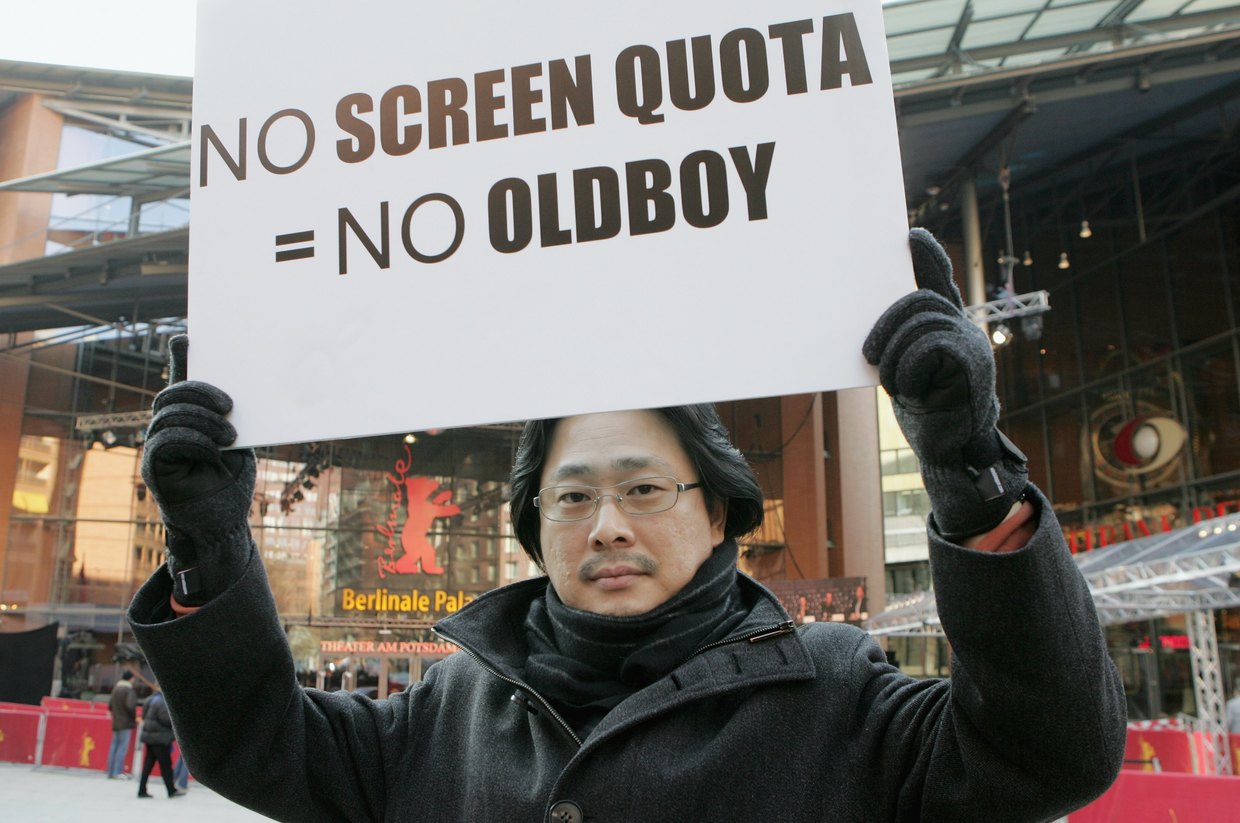

In the 1990s, the state began actively supporting Korean cinema. This is sometimes attributed to the fact that “Jurassic Park” earned more in 1993 at the box office than Hyundai did selling cars. Investors received tax breaks, censorship restrictions no longer applied to directors and screenwriters, and for every foreign film shown, one Korean film had to be produced. Gradually, quotas were reduced, which resulted in protests that included many industry professionals. Renowned Korean actors shaved their heads and burned tapes with Hollywood films in front of the US embassy. “Oldboy” director Park Chan-wook protested at the Berlin Film Festival with a poster “No Screen Quota = No Oldboy”, and leading actor Choi Min-sik stopped acting for several years.

© MJ Kim/Getty Images

From the mid-1990s to 2001, the share of domestic films at the box office grew from 23% to 50%, and the number of movie theaters tripled. Some attribute this rise to the introduction of quotas. Despite the popularity of quotas in the cinematographic industry, their effectiveness is arguable: protectionist measures were introduced in 1988, but five years later the share of domestic cinema in Korea was no larger than 16%. Today, quotas continue to be applied (a Korean film is guaranteed a little over two months at the box office), but their relevance is still questionable. For many years in a row, Korean films have made up over half of the country’s film market, and local audiences no longer need incentives to choose domestically-produced movies over foreign options.

The early 90s brought a new generation of Korean directors. They consisted of both “festival” auteurs like Park Chan-wook, Hong Sang-soo, and Kim Ki-duk and mainstream film directors such as Kim Jee-woon, and Yeon Sang-ho.

Fans of South Korean cinema often contrast it with Hollywood. One of the arguments in favor of Korean movies is that the average age of the Korean audience is 10 years older than that of the American audience. Hollywood blockbusters are primarily aimed at teenagers, while the average Korean viewer is older and more demanding.

So, what about Russia?

2022 was the first year when Russian-made movies accounted for over half of all box office receipts with a total share of 52.1%. In comparison, at this time last year 73.36% of the content shown here was foreign. January 2023 became the best month ever for Russian cinema and box office earnings topped 8,663 billion rubles ($118 million). This was a 61.8% increase from 2022 and improved on the 2020 record by 12.3%.

This success was largely due to the release of the family blockbuster “Cheburashka”, which set a record at the national box office and collected 6 billion rubles (almost twice as much as “Avatar” in 2009) or $80 million. Currently, there are several movies in post-production that may not break the record but will likely be successful. For example, “The Challenge” is set to be released in cinemas this April. This is the first feature film to be partially shot in space on the ISS.

The absence of Hollywood is already balanced by the development of domestic drama. By the end of 2022, the number of Russian films and TV series that went into production increased by 16%.

This growth has been prompted by the withdrawal of Hollywood blockbusters, which accounted for a major share of box office receipts. If Hollywood does decide to return, it will probably face much fiercer competition than before.