The Toronto Raptors 30th anniversary is naturally all about reflection, gazing back at moments everyone remembers — and some they don’t — and giving some extra thought to the turning points, crossroads, and paths not taken.

In the same way that everyone can agree the 2019 championship was the franchise’s high point, the low point is clear, too: the Raptors’ 16-66 debacle in 1997-98, when general manager Isiah Thomas quit mid-season, the team played in a baseball stadium before dwindling crowds, and Vince Carter was still dunking on people on behalf of the University of North Carolina.

In hindsight, Glen Grunwald, who became GM after Thomas’s departure, taking centre court at the old Maple Leaf Gardens in April 1998 and pledging to make things better was certainly an inflection point for what was then a star-crossed expansion franchise. “I understand your sentiments,” Grunwald told the crowd of 14,578 that day, their frustrated boos threatening to drown him out. “You have my commitment and our owners’ commitment to do everything we can to get this situation back on track.”

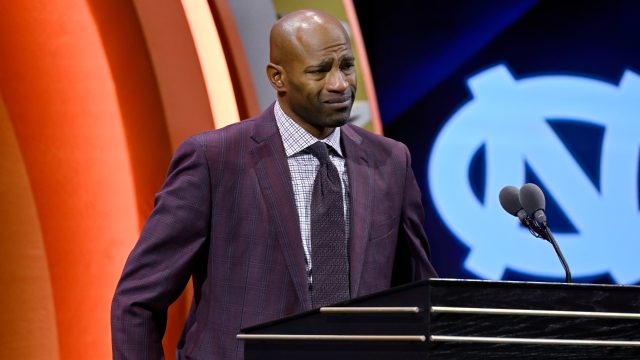

In Raptors lore, that speech serves to mark the beginning of what was the franchise’s first shining moment, one that comes full-circle Saturday night when Carter becomes the first player in franchise history to have his jersey retired and raised to the rafters.

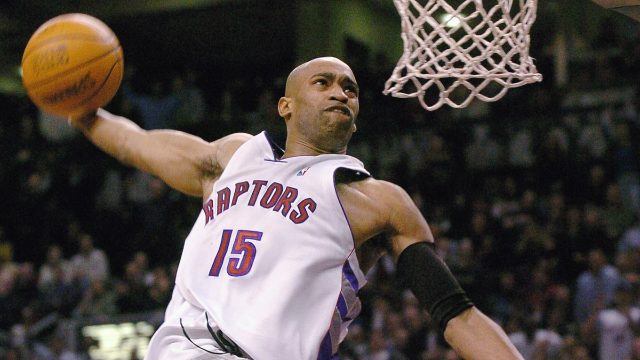

Carter was the shooting star that saved the franchise, saved basketball in Canada, and inspired a generation of Canadian players to reach unimaginable heights, or so the narrative goes. He was a high-flying, rim-rocking proof of concept that in the right circumstances, the NBA could work in Toronto, and fabulously.

So much emotion has been tied up in how Carter’s time in Toronto ended, when, after five all-star seasons and highlights that hit the basketball world like a tidal wave, the recently inducted Hall-of-Famer quiet quit his way out of town, his final weeks as a Raptor the deep ocean trench where so much of the franchise’s early dysfunction played out in real time.

But what if the real question left around Carter’s story in Toronto isn’t about how it ended, but instead what happened before he ever wore a dinosaur logo?

What if Carter’s time in Toronto had been part of an extended dynasty — an era rather than a moment?

If you appreciate basketball royalty, the scene at the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in early October was enough to make your head spin. There was Larry Bird, the legendary Celtics great somehow wedging his 6-foot-10 frame in the theatre-style seating at Symphony Hall, the historic concert venue in downtown Springfield, Mass., where the basketball greats gather each year to welcome the next class of inductees. A couple of rows ahead of Bird was Philadelphia 76ers icon Julius Erving; a couple of rows behind was Reggie Miller, the greatest shooter in NBA history not named Steph Curry. With Magic Johnson and his crew on hand to welcome their teammate Michael Cooper to the Hall, it seemed that everywhere you looked there was a Showtime Era Laker.

But if you are a Raptors fan of a certain age, your head might’ve snapped around for different reasons. Not only was Carter there to be inducted, but he was welcomed to the basketball shrine by Tracy McGrady, who played for Toronto for three seasons — two with Carter — and went on to his own Hall-of-Fame career. Getting inducted along with Carter was Chauncey Billups, best known for his role as leader of the Detroit Pistons crew that won the 2004 NBA title and played in the Eastern Conference Finals for six straight seasons, but also a former Raptor.

In fact, McGrady and Billups were teammates in Toronto during the 1997-98 season. Also on that team was Marcus Camby, the long-armed, rim-running centre who played 17 seasons in the NBA, led the league in blocked shots four times, and was named the NBA’s Defensive Player of the Year in 2006-07. Not to mention Doug Christie, the athletic wing who was named to an all-defence team four times in his career, all after he left Toronto.

That was the level of talent in Toronto even before the Raptors acquired Carter at the draft in 1998. So, conceivably, joining him in the starting lineup for his NBA debut in February 1999 could have been Billups at point guard, McGrady at forward, and Camby at centre; three Hall of Famers with a future DPOY protecting the paint, all of them 24 or younger.

“We all could have been teammates,” says McGrady, standing tall in his Hall-of-Fame jacket and shaking his head in wonder. “Man, what could have been. That would have been awesome.”

That it didn’t happen says a lot about a young franchise in turmoil, young players trying to figure out how to survive in the NBA, and a league that made development runways impossibly short.

That Carter defied all those circumstances and led Toronto to the playoffs in back-to-back years, finishing one buzzer-beating jumper away from the Eastern Conference Finals in 2000-2001, is a big reason why he’s being honoured on Saturday night.

That he had to do all of that heavy lifting almost on his own as the team’s solitary star and saviour is also big reason why he ended up leaving with such acrimony three seasons later, creating a divide that took decades to bridge.

So, back to that question: What could have been? Well, a better beginning and happier ending to his Raptors career. Maybe a world in which the 2019 championship wasn’t the Raptors’ first but one of many.

“I can’t imagine what that would have been like,” Carter told me when I asked him about the lineup that never was. “You have Marcus Camby, still young and athletic, me, T-Mac, Chauncey — with the talent on that team, we’d be viral every day, if it was today. At that time, it would have been rushing home to see what highlight [was going to be on TV]. We’d be a highlight factory. It would have been fun.”

So why didn’t it happen?

At the time, the NBA in Canada was on shaky ground, burdened massively by a Canadian dollar trading in the mid-60-cent range relative to its US counterpart, a business challenge that was a significant factor in the Vancouver Grizzlies departing for Memphis at the end of the 2000-01 season, when ‘Vin-sanity’ was at its peak. Coming off that disastrous third season in 1997-98, the focus in Toronto was on trying to prove that the Raptors were a viable business proposition.

The current Raptors can rebuild with the confidence of 30 years of market research that shows yes, basketball is popular here, and a management group with 11 years of continuity and a championship as evidence of competence. In contrast, the 1998 Raptors were an expansion franchise on the verge of having three head coaches, three owners, and two general managers to show for their three years in the NBA.

“To me that year, everyone was just trying to survive,” recalls Alvin Williams, who arrived in Toronto as part of the return when the Raptors traded Damon Stoudamire to Portland in February 1998. Williams was a rookie second-round pick with a knee that would require surgery. He didn’t look around the Raptors borrowed locker room at SkyDome or the practice court they rented at Glendon College — sharing time with badminton groups and intramural volleyball — and think ‘dynasty in the making’.

“No one really knew what the hell was going on,’” says Williams, who played seven seasons in Toronto. “No one knew Tracy was going to be Tracy McGrady. And Marcus was there, but Chauncey, I don’t think he actually wanted to be there. So it was like no one was there, putting all of that together. We weren’t together like that. Everyone was there just trying to get through a losing season.”

It was Grunwald, a first-time general manager thrust into the role after Thomas left to be a TV analyst with NBC, who felt the responsibility to right the ship. His first moves were to plug holes and bail water. Charting a course for a distant, fanciful horizon was well down the to-do list.

“You have to remember too that — and I don’t think it was true — but there was some doubt whether the Raptors would be successful and stay in Toronto at the time,” Grunwald says. “So, we wanted to show that we could win here and we could be successful, because that was always the question from basketball people: ‘You can never win in Toronto. Players don’t want to go there, there’s the metric system, you have to go through customs, it’s cold, blah, blah, blah.’ All that stuff. … [And] we were on maybe a quicker timeline than you might be otherwise to show that we could be a successful franchise.”

One thing that hasn’t changed in the NBA over the past 30 or so years is that winning with a young team — no matter how talented — is a difficult proposition. Coming off a 16-win season, Grunwald’s plan was to surround his young talent with veterans to support them and show them how to survive in the league.

There was urgency too, because under the terms of the NBA’s collective bargaining agreement at that time, teams only had rights over drafted players for three seasons. Today, teams have options on the third and fourth years of rookie deals, and even if they don’t reach a contract extension by the end of their fourth season, players taken in the first round are restricted free agents prior to their fifth season, giving teams the opportunity to match any deal they might be able to get in the marketplace. In addition, teams signing their own free agents in 1998 couldn’t offer bigger money or more years on a contract than any of their competitors — changes negotiated into subsequent CBAs to create better chances to keep players they’ve drafted and developed.

The setup in 1997-98 meant that teams had much shorter development timelines than we’re accustomed to in the NBA of today. It might seem unfathomable now that a struggling expansion team would trade away budding young stars for mid- or late-career veterans, but the rules of the game were different then — player development wasn’t a job description. “Assistant coaches would stay and help you get shots up,” says Williams, “but it’s not like now. Back then, it was up to the players to seek it out.”

Today, the Raptors have nine assistant coaches to make sure players get the attention required, and a handful more staff who, among other duties, are workout partners for the players — not to mention the Raptors 905 G League program. No stone is left unturned.

Grunwald needed to pick a path and letting his young talent marinate didn’t feel like an option. With McGrady already on the team and Carter about to be drafted, the Raptors decided their best strategy was to build a veteran group around the two dynamic wings and hope the pair would be their all-star core for a decade to come.

The biggest move was trading Camby, then the Raptors’ most proven young commodity. An athletic seven-footer, Camby was the No. 2 pick in the 1996 draft and earned first-team all-rookie honours. In his second season, 1997-98, he averaged 12.7 points and 7.4 rebounds a game while leading the NBA in blocked shots per game with 3.7, which remains a Raptors record. On the same night that Grunwald addressed the crowd at Maple Leaf Gardens, Camby recorded the first triple-double in franchise history, and the only one featuring blocked shots, as he finished with 13 points, 11 rebounds, and 10 blocks in 30 minutes. The Raptors lost the game by 29, which is kind of perfect.

“When we went through the draft where we got another good talent in Vince, we saw the need to add some veteran experience, some veteran leadership around him,” says Grunwald. “And we didn’t think that Marcus was going to reach his full potential with us, at least [not]quickly.”

Camby was the centrepiece of a trade with the New York Knicks that brought Charles Oakley to Toronto (along with current Brooklyn Nets general manager Sean Marks). It was a deal that worked for both teams, at least in the short term. Camby was the young, athletic spark the ageing Knicks needed. He helped New York advance to the 1999 Finals as the eighth seed, eventually starting three games against the soon-to-be-champion San Antonio Spurs as Patrick Ewing missed the end of the series with an injury. And Oakley became a Raptors legend in his own right and provided the bruising toughness and direct leadership Carter needed to thrive early in his career. “Oak put his arm around me on Day 1,” says Carter.

Billups’ situation was different. He’d come to the Raptors by way of trade when the Boston Celtics, struggling under Rick Pitino and unwilling to be patient with a rookie point guard, made the unusual move of trading their No. 3 pick in his rookie season. Billups played 29 games for the Raptors and, allowing for the fact he was just 21 years old and playing point guard for the worst team in the NBA, he showed promise. He averaged 11.2 points, 3.3 assists and 1.0 steals while playing 32 minutes a game. He had 27 points and five assists in a win over the Grizzlies shortly after being traded and had 26 points, six assists, and three steals in a loss to Utah a little after that. He played 36 minutes and didn’t have a turnover in a game the Raptors lost to the defending-champion Chicago Bulls by two points.

“It was a weird stage in my career, but I remember being excited to be there,” said Billups, when I caught up with him at his Hall of Fame ceremony. “My little tenure in Boston, it just wasn’t fun. I remember going to Toronto, playing for [Raptors head coach Butch Carter], I was having fun, playing kind of loose, not having to think so much. I remember having some really good games. We [almost]beat the Bulls one game, there were some really fun times. The game became fun again for me when I got to Toronto.”

But Billups wasn’t long for the Raptors. The team signed veteran point guard Mark Jackson as a free agent. On the eve of training camp prior to the lockout-shortened 1998-99 season, the Denver native was sent to his hometown Nuggets in a three-team trade that netted Toronto a pair of first-round picks — one of which the Raptors used to take Morris Peterson in 2000 and the other used in the deal that landed Antonio Davis from Indiana. Davis became an all-star and was perhaps the second-best player behind Carter on Toronto’s best teams of that era. Peterson played seven seasons for the Raptors and is third all-time in games played and seventh in points for the franchise.

Still, in the space of one off-season while trying to build around a pair of young wings in Carter and McGrady, the Raptors traded two top-three picks before their second (Billups) and third (Camby) NBA seasons.

There is almost no precedent for it in the current NBA, where top prospects are given the white glove treatment from the moment teams selected them. It’s not unheard of for players taken that high in the draft to be traded so early in their careers, but that’s usually because a team is cutting bait early on a mistake (James Wiseman, taken second overall by the Golden State Warriors in 2020, is an example) or including the young talent in a championship-or-bust type deal, such as the Lakers trading a pair of No. 2 picks in Brandon Ingram and Lonzo Ball as part of the package for Anthony Davis in 2019.

Could a team with Billups and Camby playing alongside McGrady and Carter have won a championship down the line? It’s hard not look at the resumes of the players the Raptors had in the fold at the lowest point in franchise history and wonder what could have been.

“Are you kidding me? You got T-Mac and you got Vince,” says Billups, who was the Finals MVP in 2004 when the Pistons won the title. “You got me and you got Camby. You let that cook for a while, who knows what could have happened.”

The other side of the argument is that Billups didn’t truly come into his own until his sixth season and his fifth NBA organization. And while Camby showed flashes of his potential, he didn’t make an all-defence team until 2004-05, his ninth season.

And every Raptors fan knows that McGrady was the one that got away: When he hit free agency in the summer of 2000, he opted to leave Toronto, leave his cousin Carter, and go home to play for the Orlando Magic.

That left Carter as the franchise’s lone star. He did the job admirably. From 1999-2000 to 2002-03, Carter played basketball as well as anyone ever has for the Raptors, averaging 26 points, 5.6 rebounds, 3.9 assists, and 1.5 steals for a team that made the playoffs each year. Before the injuries and the acrimony, he provided a generation’s worth of memories that justify his jersey retirement tonight.

It was a magical period of potential that ended too soon, and it’s possible the best possible version of it — Carter as the centrepiece of a roster stocked with young and athletic future stars — was over before it ever even began.