TORONTO — A lot changes in a year. And a lot doesn’t.

I started this annual column off in 2023 with the line “patience isn’t free.” After the Toronto Raptors opted not to be sellers — even buying — at last year’s trade deadline, I warned that, while I could see the logic, there is an eventual cost to rolling flexibility into the future. Players get older or get closer to free agency, the value of players and contracts change, and the NBA landscape shifts.

In the year that’s followed, the Raptors have overhauled a lot. Three of the four players they chose not to move last deadline are gone, with Fred VanVleet leaving for nothing in free agency, Pascal Siakam being dealt for less (arguably, and in my estimation) than he would have if traded earlier, OG Anunoby being traded for a very solid return, and Gary Trent Jr. still sticking around. Over the course of four trades in the past seven weeks, the Raptors have sent out eight players, dramatically overhauling what the roster looks like now and moving forward.

Despite all of that change, flexibility was still a talking point Thursday. It’s true that the Raptors made their big moves early, jumping this year’s market on Siakam and Anunoby deals. It’s also true that the Raptors are now extremely agile, from a roster and cap perspective, as they spend the next two years figuring out who and what works best around Scottie Barnes. And it’s true that at least a part of Thursday’s moves and non-moves were, once again, about pushing some decisions until later, betting that the flexibility won’t erode. It’s going to require a delicate balance, and — shocker — patience.

What follows is not a subjective analysis of the moves. It is an objective explanation as to why the Raptors made them, and where things stand heading into the 2024 off-season. Let’s reset for the remainder of this year and the summer ahead.

The trades

The Raptors acquired Kelly Olynyk and Ochai Agbaji from the Jazz for Otto Porter Jr., Kira Lewis Jr., and the worst of the 2024 first-round picks they owned from Indiana (currently projected to be the No. 28 pick). They then acquired Spencer Dinwiddie from the Nets for Dennis Schroder and Thad Young and subsequently waived Dinwiddie.

Incoming pieces, Olynyk’s next deal and why Dinwiddie was waived

Olynyk is making $12.2 million and will be an unrestricted free agent at the end of the season. He is eligible for an extension, and extensions can be signed at a lower amount than his existing deal. The Raptors will also hold his Bird rights, meaning they can exceed the cap to re-sign him in the summer, if they don’t extend him.

Olynyk would have a cap hold of $18.3 million as a free agent, limiting Toronto’s cap space. So if Olynyk is in the team’s future plans, they would either extend him soon or re-sign him immediately at the start of the off-season. Once he’s signed, his cap hold is removed and he’s on the books for his new salary. For example, if his next salary is $10 million, the Raptors would have an $18.3-million charge on their books until he signs, then it would become $10 million. (This isn’t all that important in the big picture, but the timing of the moves will matter in July.)

Agbaji is in the second year of his four-year rookie-scale contract. He makes $4.1 million this year, $4.3 million next year, and the Raptors will have until the start of next season to decide on a $6.4-million team option for 2025-26.

Dinwiddie was an expiring contract, making $18.9 million this year. The Raptors will be on the hook for the remaining portion of that, and it all counts against the cap and tax for this season. While it’s true that Dinwiddie would have earned a $1.5 million bonus if he played two games with the Raptors, this type of post-deadline waiving is fairly common. Dinwiddie is 30 and not a part of the team’s future plans. If he didn’t have the bonus, the Raptors likely would have negotiated a buyout with him anyway, similar to how Kyle Lowry and others will now be bought out around the league. The idea is to save the waiving team some real money and let a vet go to a preferred, playoff-bound destination.

Outgoing pieces and salary-dumping Schroder

Three of the players Toronto sent out are expiring contracts. Porter has some value to Utah as a vet on a play-in competitive team. Young is reportedly being waived by Brooklyn (he also had $500K in incentives he won’t reach). Utah might have some interest in seeing what Lewis can offer, but he will be non-tendered this summer and become an unrestricted free agent.

Schroder is the important piece here. It was a bit surprising to see the Raptors deal Schroder without an asset coming back. In any case, it also clears $13 million off the books for next year. It seems likely Schroder would have been movable on that contract in the off-season — it’s a reasonable price for a quality backup point guard — so this may suggest something about the fit between player and team, beyond the cap ramifications.

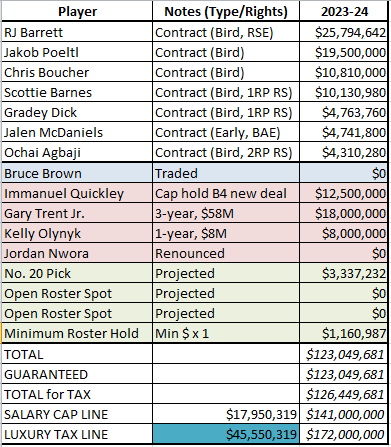

Net impact on the cap and tax sheet, updated tax space

The Raptors took back an extra $2.7 million in salary for this year between these moves. They had (and still have) plenty of space under the luxury tax, so there is no impact there. (It amounts to about $1 million in additional real money to be paid out the rest of the season.)

More importantly, the net of Schroder and Agbaji means the Raptors cleared an additional $8.7 million in space this summer. As we’ll see, that may or may not matter for free agents specifically, but it should be helpful.

The Raptors remain $2.6 million below the tax, and really that’s more like $6.4 million, as a number of players have bonuses they are extremely unlikely to hit. Basically, the Raptors have plenty of room to sign new players the rest of the season and not remotely sweat the tax.

What happens with the open roster spots, and how two-ways factor in

The trades and Dinwiddie waiver leave the Raptors with two open roster spots. As noted, they have plenty of room under the tax to fill those spots, though they can only offer minimum contracts. They have two weeks to fill the first spot and don’t have to fill the second spot at all (though they should, these are valuable looks at developmental pieces).

One route for filling the spots would be to promote two of the two-way players — Jontay Porter, Javon Freeman-Liberty and Markquis Nowell — to full-time NBA contracts.

That’s always something I’m in favour of to reward your internal players, but there are a few smaller arguments against it. First, you’d then have to backfill the two-way spots by finding new two-ways, and the pool of potential two-way players is thinner than the pool for NBA players because two-way eligibility is somewhat limited. Second, if you really like the two-ways long-term, you can sign them to a longer contract (four years) if you wait until the off-season than if you do it now (this year plus next year only). The Raptors’ three two-ways can all play as many NBA games as the team wants from here (they won’t hit the maximum), so it’s possible the Raptors see more value in keeping the two-ways as two-ways, calling them up as needed, and using the two open roster spots on other players.

If the Raptors look outside of their own roster, there are a number of interesting G League guards out there, but very few bigs. Justise Winslow and Mo Gueye would be the Raptors 905 options to promote, even on 10-day contracts, but their path to playing time could be tough. The Raptors could also look overseas at players whose seasons are wrapping up soon or have NBA opt-outs, getting an early start on moves that are usually saved for July.

The team could also rotate through a few 10-day contracts to get a look at multiple players before deciding who to sign for the rest of the season (and possibly next year).

The 2024 off-season outlook and key decisions ahead

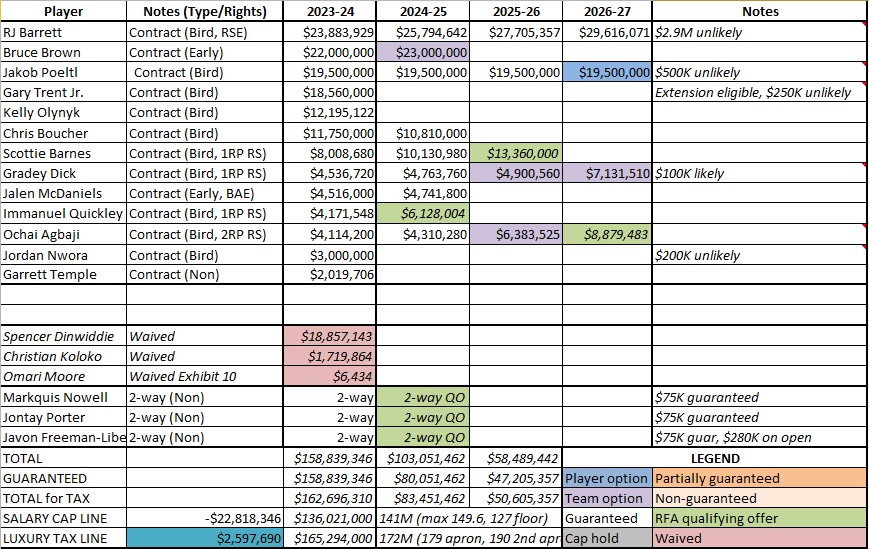

The table above gives us a good first snapshot of the off-season ahead. The Raptors only have seven players under guaranteed contract, and they’ll earn a combined $80.1 million. With the cap currently projected to come in at $141 million and the luxury tax at $172 million, the Raptors will have loads of flexibility.

Whether that flexibility comes in the form of true cap space is to be determined. There are five pretty big questions that will determine what the Raptors’ 2024 off-season path is.

1. Do they pick up Bruce Brown’s team option?

Brown still being on the roster today is probably the biggest surprise of Toronto’s deadline. They did not get the offer they were looking for, and they will roll the flexibility Brown’s contract provides over into the off-season. Now, Brown can be either a $22-million chip for matching salary at the draft, a $23-million player to be dealt in July (there is no restriction on him at either date), a $23-million player for the Raptors’ 2024-25 roster, or the Raptors can decline his option and just take the cap space.

The latter option is, obviously, the worst from an asset-management standpoint. The Raptors’ message on Thursday was that they believe Brown will retain plenty of value into the off-season as a win-now piece on a short contract. That’s surely true, but he’s less valuable to teams today than he was yesterday.

2. What does Immanuel Quickley’s next deal look like?

Functionally, this isn’t all that important, as Quickley has a small $12.5-million cap hold. That will allow the Raptors to just keep his cap hold on the books, do the shopping they need to do, then re-sign Quickley to his new, higher salary. It’s the opposite of what I mentioned earlier with Olynyk’s timing.

3. What happens with Olynyk?

As explained above, it will make sense to figure out his next contract as soon as possible to turn his high cap hold into his new, smaller salary.

4. What happens with Gary Trent Jr.?

Like Olynyk, he’s extension eligible, but there’s been little smoke about a new deal, and Bobby Webster was noncommittal Thursday. Trent would carry a $27.8-million cap hold, eating up a lot of flexibility, so the Raptors will want to either work out a new deal with him, sign-and-trade him, or renounce his rights for nothing if they’re prioritizing maximum cap space.

5. What happens with everyone else?

Chris Boucher’s $10.8 million for 2024-25 wasn’t able to secure an asset at the deadline, but it could find a home next year as an expiring deal, opening up more space. Jordan Nwora will also have a $5.7-million cap hold the Raptors will want to remove by renouncing him or re-signing him to a smaller deal.

2024 off-season cap scenarios

That’s a lot of ifs. Let’s play out the two most extreme scenarios.

The first is that everyone stays on the books (except Garrett Temple), the Raptors win the draft lottery and pick first with their own pick, the Pacers pick they own lands at 15, and the Raptors opt to keep one roster spot open (for now) for a free agent. (Let’s say their second-round pick signs a two-way, for illustrative purposes.)

In that extreme scenario, the Raptors don’t have cap space. The cap holds for their free agents and draft picks are large enough that all the theoretical space is eaten up. Obviously, you’d have to make additional moves if you wanted to supplement this group in free agency beyond exceptions and minimum contracts.

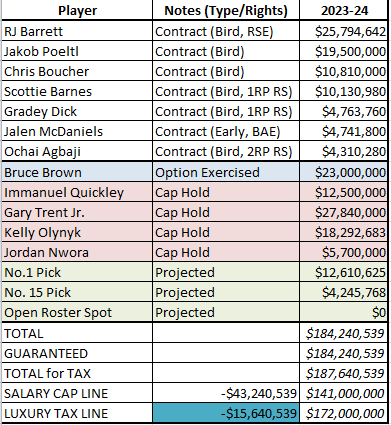

The other extreme is the Raptors clearing the deck completely. Their pick conveys to San Antonio, they decide to move on from Brown and their other free agents, and the Pacers pick lands at 20. (There’s a small minimum-roster charge in this scenario, as the CBA forces you to have 12 contracts, real or fake.)

In this scenario, the Raptors have $53 million in cap space, which is enough for a max free agent or multiple players beyond what the mid-level exception ($12.9 million) can get you. That would cost you Brown, Olynyk, Trent, Quickley, and Nwora, so it’s not practical, but if all you cared about was cap space, that’s how it’d look (and that’s before maybe finding homes for Boucher and Jalen McDaniels, which could clear another $15.6 million).

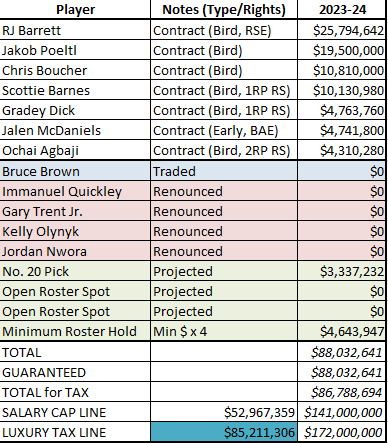

Realistically, the Raptors will do something in between. Say, for example, they trade Brown at the draft for future picks, re-sign Olynyk to an $8-million deal, let Nwora walk, re-sign Quickley (but keep him on as a cap hold for now to maximize space), re-sign Trent to a deal with a starting salary of $18 million, and the Pacers pick lands at No. 20.

Here, the Raptors land with $18 million in cap space, which is more than the mid-level exception and gives the team some buying power with second-tier free agents.

Is cap space actually all that useful?

We could do a dozen iterations in between the extremes, including those where the Raptors keep Brown, sign-and-trade Trent, trade out of the first round, and so on. The main takeaway is that they could create upwards of $50 million in cap space if they needed to, it just comes at a cost of losing a lot of players for nothing in free agency or for less in trade than you might get if you didn’t mind taking salary back.

This all leads to this question: Is this flexibility all that useful if opening it up carries such opportunity costs?

First, yes, it is useful. Even if it’s unsexy, having multiple paths and multiple leverage points along the way is good. There are diminishing returns to that flexibility, and to rolling it over into the future (as we’ve perhaps seen), but it’s a real asset.

It may not be useful as cap space, though. Or, rather, it may not be most useful as cap space. Cap flexibility can be leveraged in a number of ways, including taking back extra salary in trades to add helpful players, or “renting” out your cap space by taking on a bad salary and picking up assets for your trouble. The latter example isn’t exactly fan-friendly, but it’s been a big part of how teams like the Thunder built up additional assets during a rebuild, since signing free agents wouldn’t do much for them at that point. This is especially notable heading into the 2024 off-season, which could be one of the most difficult ever on high-spending teams as further roster-building restrictions are put on deep-tax teams.

The answer to what the Raptors will do with all this flexibility is hard to figure right now. In their eyes, it seems that “well there are a lot of options” is a good answer. They can create cap space to sign good free agents that fit the core, take on good players in trade without worrying about sending out matching salary, retain all their players, pick up assets to take on bad contracts, or any number of combinations of those different options.

Again, I realize that explanation is not always the most popular, but this article is just an explanation of their thinking (or how I read their thinking from outside).

Key Takeaways

• The Raptors took on a bit of salary this year to clear more salary for next year in these deals.

• They now have two open roster spots to sign players to minimum contracts, 10-day contracts, or promote the two-ways. There are no concerns about nearing the luxury tax.

• They can clear upwards of $50 million in cap space for this summer, but it would require losing a lot of pieces to do so. The likelier path is using the flexibility for a combination of re-signings, signings, and trades, without ever actually clearing out maximum space.

• Brown’s team option, a small cap hold for Quickley as an RFA, and Olynyk’s next deal likely being cheaper than his current deal all give the Raptors some additional flexibility with respect to timing and structuring their off-season moves. Brown’s flexibility — trade at the draft, decline the option, pick up the option to trade, pick up the option to keep — depends to some extent on the market for him and should be an early bellwether for Toronto’s plans.

• The Raptors have their own pick in 2024 only if it lands in the top six, Indiana’s 2024 pick as long as it doesn’t land in the top three, all of their own future firsts, and Indiana’s 2026 first (top-four protected), plus a second in every year except 2025. The draft cupboard is basically restocked and at a small surplus.

• There are only three players on the roster — Barnes, Trent and Boucher — who were on the roster before last year’s trade deadline. That is a ton of roster turnover for the current off-season plan to be “well, we’ll see.” But, well, we’ll see. Optionality in a multi-year restructuring is an unsexy necessity.