Football’s “prevent” defence is often referenced in other sports, having found itself tied to the running joke that all it does is “prevent you from winning.”

The idea is simple: late in games the leading team eliminates the possibility of big plays downfield by backing their defence off and keeping the game in front of their defending players. They may allow some plays underneath, but are content taking away the possibility of “home run”-type plays behind them. The defence encourages “successful” plays of smaller yardages that run the clock, forces the offence to use their timeouts, and essentially tries to bleed them of their time before they can piece their way downfield.

The gag that the prevent defence “prevents you from winning” comes from the fact that sometimes the offensive team can bite off chunks of 15-20 yards in successive plays “underneath” the ultra-passive defence, and find itself in scoring territory fairly quickly.

As John Tortorella once said about hockey: “safe is death.” And sometimes – like when your opponent has an elite offence – it certainly can be.

But in truth, football’s prevent defence is more like the drop play on NHL power plays: everybody hates watching it so when it fails they highlight it. But teams keep doing it because it works more often than any other commonly used strategy to date.

It’s with this in mind I bring to you the latest update on Ice Tilt, a metric that uses NHL EDGE IQ data to show us where the players are on the rink over a rolling period of two minutes to highlight in-game momentum. Where has the actual hockey been played on the rink over the course of a game? And what does that tell us about that game?

The Edmonton Oilers have heavily controlled the tilt in their series versus the Vancouver Canucks, yet find themselves trailing in the series two games to one.

How does that happen?

Hockey’s version of the “prevent” is simple. When you’re forechecking or defending in the neutral zone and a 50/50 puck pops loose, you simply back off rather than race at it and risk getting beat clean. You allow your opponent to get to it, but you stay between them and your own net. You’re OK with them having the puck, but you’re not OK with them having an odd-man rush or fast break of any kind, so you stop taking risks.

When you’re in the defensive zone, that means you’re OK with your opponent having the puck out by the yellow paint, but the second they start to come into the danger areas, your team acts like the slot is a hornet nest and attacks aggressively.

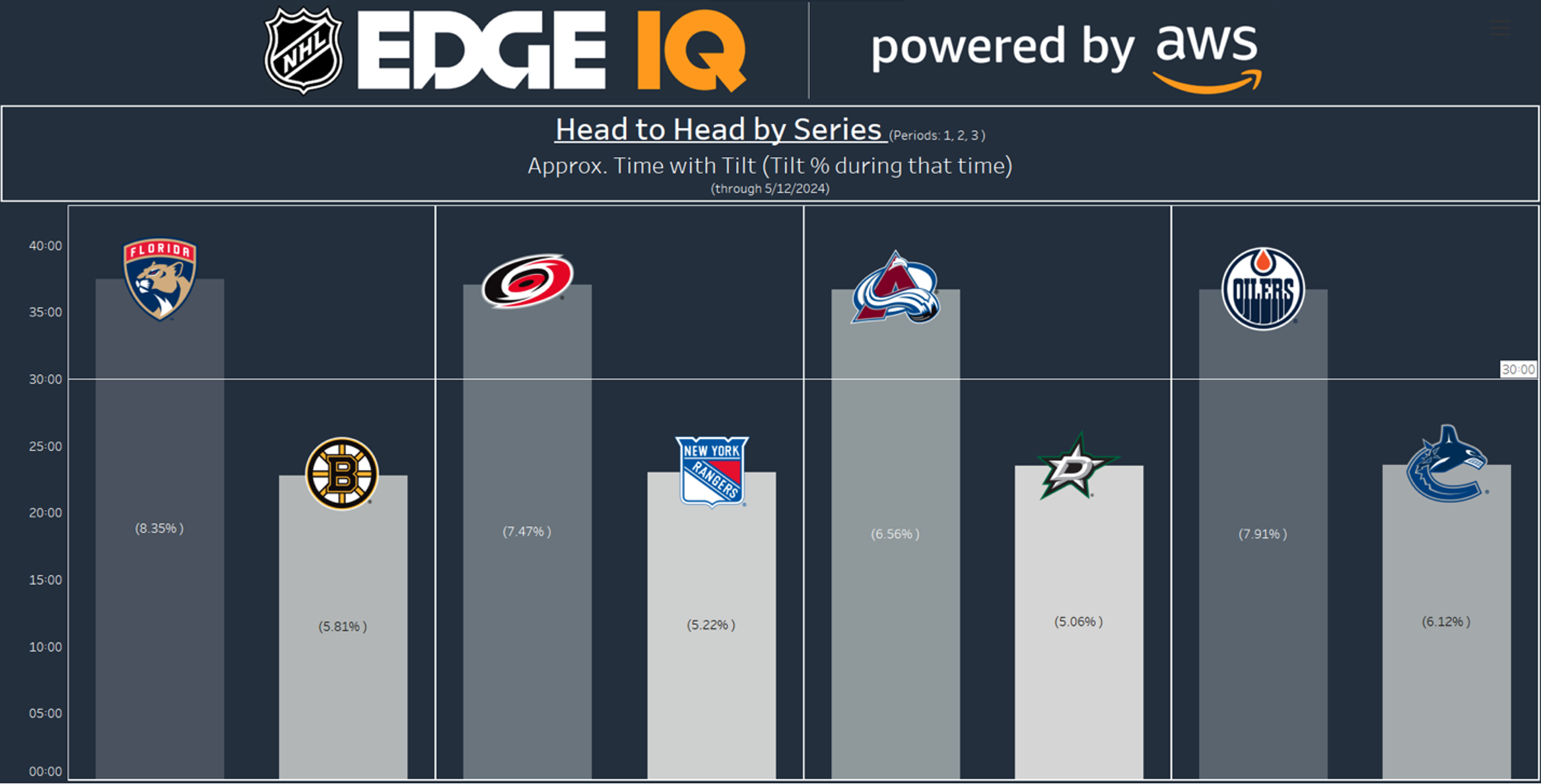

Let’s take a look at the teams that have controlled the Ice Tilt in their series so far. You’ll see that three of the trailing teams have controlled tilt as they chase games, with Florida being the outlier, both winning the series and leading in time with tilt.

The percentage on the bars simply refers to how deep past the centre red line the players have been during their “tilt,” so a higher percentage past centre means they’re closer to the offensive net. (If half the rink is 50 per cent, I like to add that to the total. The average player on Edmonton has been 57.91 per cent of the way up the rink from their own net, for example.)

As mentioned, Florida is the only team in the second round that both controls tilt and is ahead in their series. It’s worth noting, though, that the Panthers were chasing the scoreboard for a lot of Game 4 before coming back, tying it, and eventually winning the game. Even with that Ice Tilt help they have controlled their series against the Bruins, and are prohibitive favourites to finish the job quickly.

What we’re talking about here, with losing teams having tilt, is a concept that’s been accepted in advanced analytics for a long time: score effects. Teams change how they play based on the scoreboard.

I’ve seen Canucks fans upset at the notion that they’re fluking their way to victories based on the difference in goaltending, rather than just strategically playing to their leads, and they have a point.

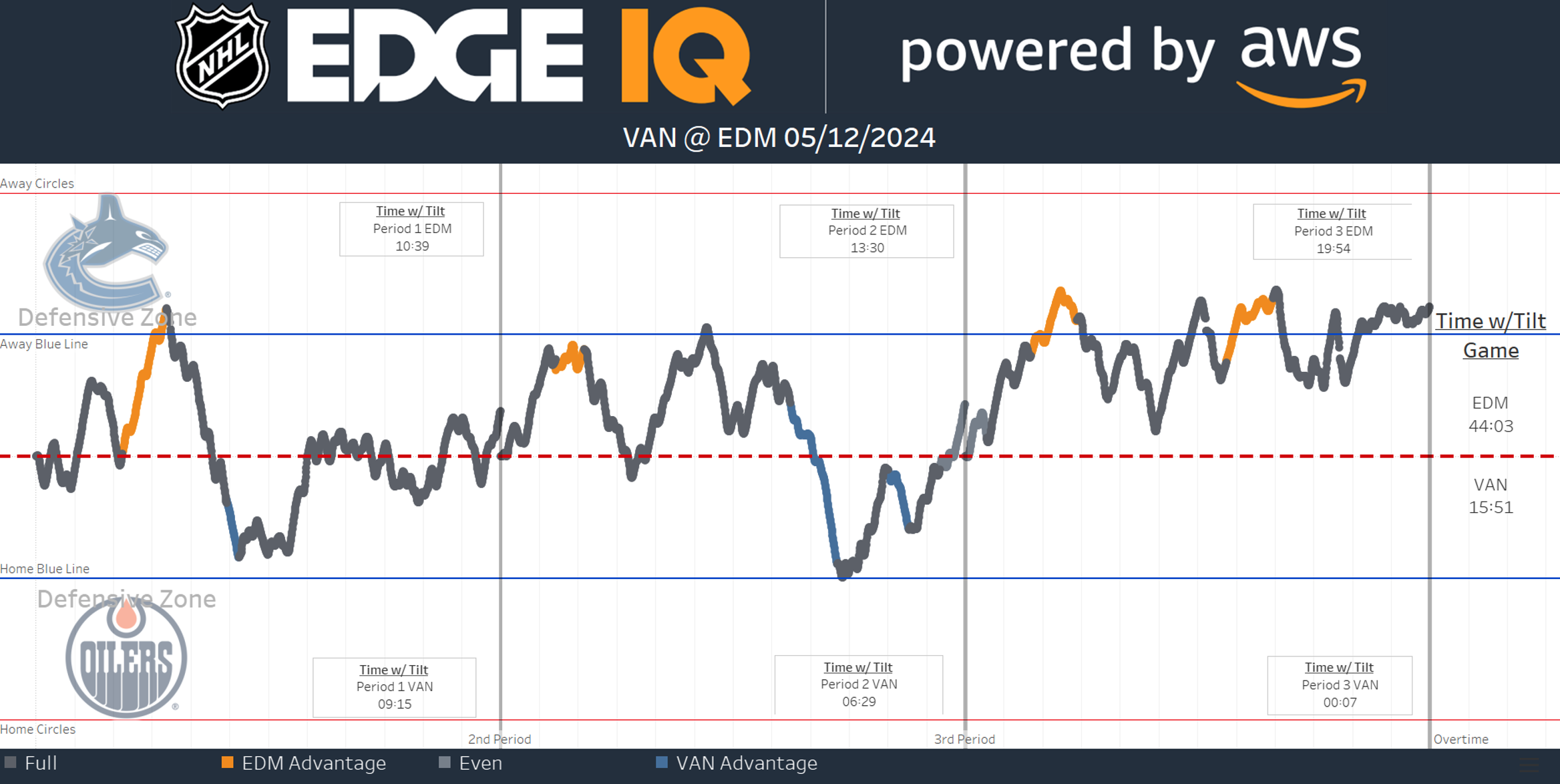

In the third period of Game 3 in the Canucks-Oilers series, tilt swung heavily in favour of Edmonton and the rolling average of tilt over two minute chunks only swung in Vancouver’s favour for seven seconds of the period, leaving 19:53 for the Oilers. That led to a third period shot count of 22-3. Looking at where the centre red line is here, you can see the third period isn’t exactly a tennis match of back-and-forth play.

This is where I loop it back to the concept of “prevent” defence. At even strength I’ve seen “high danger chances” recorded as either 1-1 or 2-1 Edmonton in that third period, which is staggering considering where the players were located.

If you’re the Vancouver Canucks, is that not exactly the desired outcome? You trust that your goalie can handle the lower danger stuff from distance (at this point every goalie in the NHL should be able to confidently do that) and the rest of the job is keeping the other team’s high danger chances down.

You can quibble with the logic – many fans will say “just go score yourself and put the game out of reach,” and I’m fine with having that philosophical debate. But as of right now, Ice Tilt really highlights the degree to which NHL coaches disagree with that line of thinking, and prefer to pack it in with a lead.

Teams that are trailing a game open it up and chase the score. Teams leading want to take away the deep touchdown pass and keep the opposing offence in front of them.

This just goes to show how important early leads are. The Oilers are one of the best offensive teams in the NHL, but when the Canucks pack it in in front of Arturs Silovs, the surprising Latvian suddenly looks like prime Patrick Roy, and scoring at 5-on-5 becomes an uphill climb, even with the ice tilted the right direction.