NEVER IN A MILLION YEARS

Editor’s Note: The following story deals with sexual assault, and may be distressing for some readers.

If you or someone you know is in need of support, those in Canada can find province-specific centres, crisis lines and services here. For readers in America, a list of resources and references for survivors and their loved ones can be found here.

I

t was opening night at Mosaic Place, the new home of the Moose Jaw Warriors for the 2011-12 WHL season. Fans walked a red carpet into the arena, Warriors mascot Mortimer J. Moose rode a limo onto the ice, and fireworks exploded along with the sold-out crowd of 4,480 as the home team’s roster was announced.

Cody Beach was fired up to get the season started, having just returned from training camp with the St. Louis Blues, who’d drafted him in the fifth round the summer before. The six-foot-six enforcer was already a fan favourite in Moose Jaw, after ranking second in the league in penalty minutes while putting up nearly a point per game the previous season. No. 16 was so recognizable in the city that if he went through a local Tim Horton’s drive-through the morning after a game, the person handing him his coffee would also offer something like: “Nice assist!” or “Why’d you take that stupid penalty?”

In the third period of this first game in the Warriors’ new home, Beach gave fans yet another reason to talk about him. Linesman Sean Dufour was working the game and he vividly remembers the moment now more than a decade old, as Beach closed in on an opposing player with the puck. “Cody absolutely crushed him,” Dufour says. The whistle blew and Beach was immediately escorted off the ice, given a major and a game misconduct for a hit to the head. “The fans were going bonkers,” Dufour says.

That season, Beach led the league with 229 penalty minutes while maintaining his nearly point-per-game pace. The Warriors made the WHL’s eastern conference final, and in 13 post-season games, he had 10 points and 29 penalty minutes to close out his junior career. Beach played less than two full seasons for the Warriors, but his impact is lasting: Today, you can order “Cody Beach” chicken wings at the downtown Déjà vu Café. “The guy’s a legend around Moose Jaw,” says Dufour, who lives there. “I call him ‘The Mayor.’”

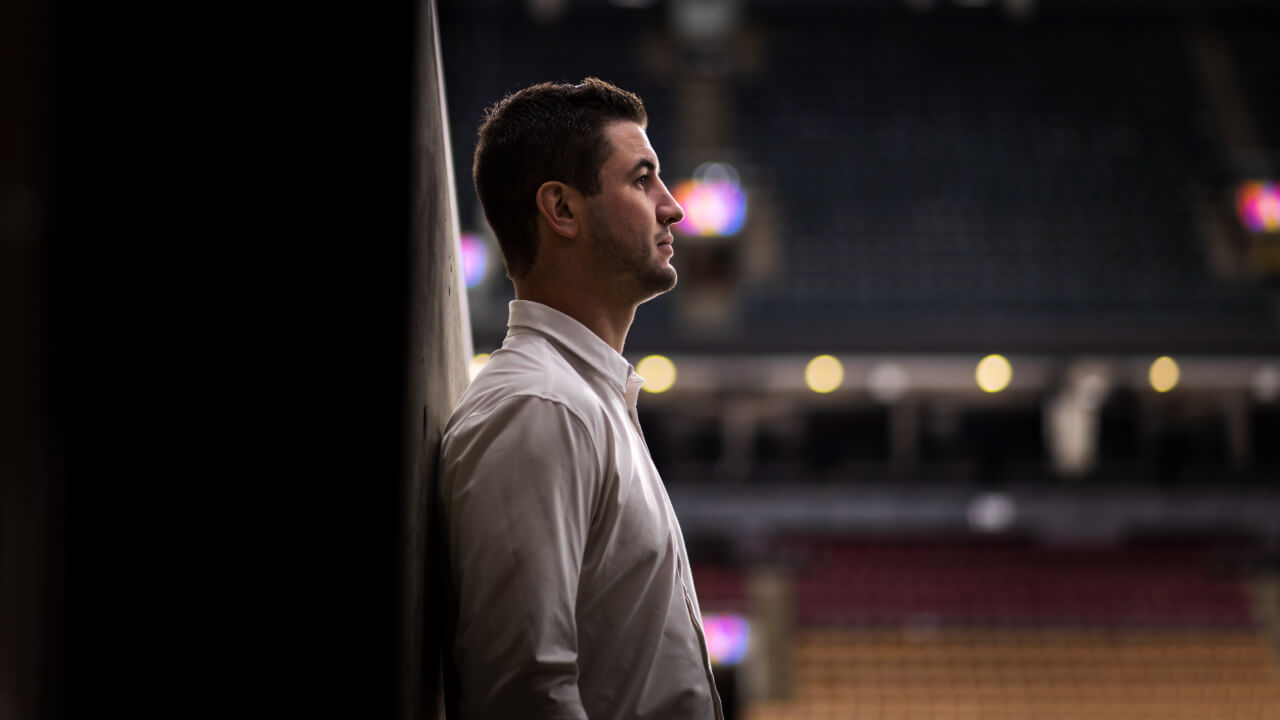

Moose Jaw’s unofficial mayor is now sitting in the lower bowl of Scotiabank Arena while the Toronto Maple Leafs have their morning skate ahead of a preseason game. Beach remembers well the amped up crowd and what he now calls a “careless hit” he delivered the night Mosaic opened. The 30-year-old is dressed in a crisp white button-up shirt and dark dress pants, and his long legs are stretched into the space intended for the empty seat beside him. In about eight hours, he’ll take the ice below and skate on the stage he’s been dreaming of since he was three years old. “I get a little nervous before every game,” he says, with a grin. “Nervous and excited.”

When Beach steps out there tonight, he won’t be wearing the jersey of an NHL team. Instead, he’ll be in a uniform he never could’ve pictured himself donning during his playing days: The former enforcer who was an expert at bending and breaking the rules is now enforcing them as a referee at the pro level. And everyone who knew Beach as a player is more than a little surprised to learn about this stark career change. “It’s crazy,” says Ty Rattie, who played with Beach for parts of three seasons with the AHL’s Chicago Wolves. “Knowing the type of menace he used to be to the refs and to opposing players? I’m as shocked as anyone.”

The fact that Cody Beach is here as a referee is not surprising only because of his reputation as a player, though. He stuck with this game and worked hard to find a new role within it despite the fact hockey has caused Beach and his family unimaginable heartbreak, the type that could’ve driven a person to walk away from the sport forever. Beach’s playing career ended so badly that for months he couldn’t bear to even watch the game on TV. A few years later, his older brother Kyle told Beach he was sexually assaulted by Blackhawks video coach Brad Aldrich during Chicago’s 2010 Stanley Cup championship run. The childhood dream script of life in pro hockey had, at times, played out like a nightmare, and yet Beach refused to give up on this game. And now that he has begun to realize his goal of a career in the NHL on this second chance, he’s focused on ensuring he’s good enough to appear regularly on those game sheets, and in big games, just like he and Kyle both hoped they would.

Had you told Beach a decade ago that he’d one day be here on this stage, but as a referee, he wouldn’t have been able to respond in words. “I would’ve just been laughing,” he says, looking down at the ice below. “But here we are.”

A

s a kid in the Kelowna Minor Hockey system, Beach was a top-line forward, but never the star regularly lighting the lamp, never the best on his rep teams. “I was always a complementary player,” he explains.

His job was to get the all-stars the puck. “He was a skilled guy, a great passer,” says one of those all-stars, Cody Sylvester, who grew up playing with Beach. “He was always setting guys up. Cody had great hockey sense.”

He also had a sense he’d need to adopt a new role to have a pro career. The summer before high school, Beach sprouted from five-foot-eight to six-foot-four, and managed to settle into that new frame quickly. The Calgary Hitmen selected him 58th overall in the 2007 CHL draft, and a year later, Beach was in Ottawa with his family as they watched the Blackhawks announce Kyle as their first-round draft pick. Seeing his brother go 11th overall further motivated Beach to one day get drafted to the NHL himself. “I was fortunate to have Kyle as an older brother — he led the way for us,” Beach says. “I got to see his path, I got to see him grow. But he was one of those players that was in the limelight because he was the best player at his age group, whereas I wasn’t.”

Ahead of his WHL rookie season in 2009-10, Beach knew ice time would be at a premium on a stacked Hitmen roster. To that point, the only fights he’d been in were brotherly brawls with Kyle on the family’s backyard trampoline or over mini sticks in the basement. But when a young teammate took a hard hit during an exhibition game, the 17-year-old Beach dropped his gloves and fought a veteran player. It didn’t go half bad, either. “I wouldn’t say I won, but I was still standing after the fight,” he says. “And still in one piece.”

From that moment on, Beach adopted a new role to prove himself valuable to the team. “I transitioned a little bit into making my teammates comfortable, whether that meant having to get into a fight or telling someone to stay away from them,” he says, messages that definitely weren’t delivered quite so politely.

Beach calls it an “easy change” to become an enforcer, in part because of his size, but says the role didn’t come naturally, and instead felt like a job. It was one he thrived at out of the gate: Beach led all WHL rookies in penalty minutes, with 157 in 51 games.

Sylvester was on that Calgary team, too, and he wasn’t surprised to see his childhood buddy own that role. “He’s always been that player that likes to play a little dirty and get under a guy’s skin, and if you’re going to play that way, eventually you’re going to have to drop the gloves,” says Sylvester, who now plays in the ECHL. “Those are the types of guys you want on your team, because they’re always stickin’ ya, always going after you when the ref’s not looking. He really stuck up for his teammates.”

That 2009-10 season, the Hitmen won the WHL championship and went on to the Memorial Cup, where they lost in the semi-final. A couple of weeks later, the Blues drafted Beach 134th overall — ahead of the likes of Mark Stone and Brendan Gallagher — which he calls “the cherry on top” of an incredible year. “Hearing the phone ring and having [Blues GM] Doug Armstrong on the other end of the line was just unforgettable,” he says. “That’s kind of when it came to fruition for real, that you’re in that top group of players.”

That same year, Kyle was part of what appeared to be an incredible season as a practice player, a black ace on Chicago’s 2010 run to the Stanley Cup. Everything was lining up the way Beach dreamt — or at least that’s how it looked on paper.

I

t was the summer of 2012, and the Beach brothers were among a group of 20 buddies, all in their early 20s, headed out to Golden, B.C., for a river rafting trip. Cody was just weeks away from the start of his first professional season, which he’d split between the ECHL and the AHL, while Kyle would return to Rockford to play for the Blackhawks’ AHL affiliate.

The fellas were having a blast, but during a quiet moment, Kyle pulled his younger brother aside for a talk and things turned serious. Kyle started off with some brotherly life advice, and then he teared up. “I’d never seen my brother cry or break down in his life,” Beach says. “I was so caught off guard.”

As Beach remembers it, Kyle told him that being a black ace during Chicago’s championship run two years earlier “wasn’t as great as what it looked like.” Beach was shocked. “From our [family’s] perspective, we thought he was doing this Stanley Cup run and being a part of it, and what kid wouldn’t want to do that? That’s what we dream of,” Beach says. “What we saw his experience as was not the experience he had. But I didn’t know the extent of why.”

And 10 years ago, Beach didn’t ask: What wasn’t great? What went wrong?

Today, with the Maple Leafs practising below, his brown eyes well up as he thinks about how badly he wishes he continued that conversation. “Here I was a young guy, not asking questions, kind of living life by: ‘We’re young, and we’re living life, right? What bad can happen to us? We’re making money playing hockey and living a dream that we both want to live. What wrong could be happening?’” he says. “At the time, I knew how strong my brother was, so I didn’t put much thought into it and didn’t put much emphasis or care, to be honest, in asking, ‘Hey, you brought this up. What happened?’ I never circled back on it.

“But if my brother’s breaking down, we’re not joking around here,” Beach adds. “Something had happened.”

He just didn’t know what.

More than a decade later, in October of 2021, Kyle revealed that he was the player identified as John Doe in a negligence lawsuit filed against the Blackhawks. He sat down for an interview with TSN’s Rick Westhead to share details of his story for the first time on camera. Kyle said he was sexually assaulted by Aldrich when he was 20 years old, that the coach then threatened Kyle’s career and told him he would never play in the NHL if he told anyone about what had happened. Kyle recalled feeling alone, like he couldn’t turn to anybody for help.

Kyle said he reported the incident to Blackhawks staff and was told it had been shared up the chain of command, but Aldrich remained with the team through the end of that season. Kyle said he felt sick to his stomach as he watched Aldrich lift the Stanley Cup at the championship parade. Teammates, Kyle said, had been using homophobic slurs towards him — suggesting the assault wasn’t a secret. The NHLPA was also made aware of the allegations, Kyle said, and he received no support from the union that exists to protect players. As Kyle told Westhead, he buried all this trauma for more than a decade, “and it has destroyed me from the inside out.”

Kyle had told his parents about the sexual assault not long after he says it occurred, and they shared some of those horrific details with Beach a few months before Kyle’s interview aired. Beach was in Laval refereeing a game the day of the broadcast and learned much of Kyle’s story as he watched his brother’s interview later that night. “I didn’t know the full extent until the rest of the world knew,” Beach says, his voice breaking up. “That’s how caught off guard I was.”

And by that point, Beach’s relationship to hockey was already headed down a completely different path.

O

n one level, Beach’s first on-ice transformation was simple. He had the physical tools to be an enforcer, among them, as Rattie points out, “really, really long arms, this big jaw and a big head.” It was just learning how and when to apply those tools that took time.

Mike Stothers, Beach’s coach during his final WHL season in Moose Jaw, remembers the subject coming up in more than a couple of meetings, where he also tried to ensure his enforcer was keying in on other parts of his game. “I think maybe what was overlooked because he was such a tough individual was his hands — he had a great set of mitts on him, and he could really make plays,” says Stothers, who’s now an assistant coach with the Anaheim Ducks. “But sometimes, he was his own worst enemy. I mean, he was a tough kid, right? He protected his teammates well. He’s a good person. He just got a little distracted sometimes and had trouble staying focused.

“What I remember of Beacher, regardless of whether he was fighting or playing, he played hard. He cared about his teammates, and he always wanted to do well by them. And you know what? You can’t ask for a better guy, wearing his heart on his sleeve.”

Rattie played against Beach at the junior level, and recalls Beach was “just scary.” When the two became teammates during Beach’s second pro season, with the AHL’s Wolves, Rattie was surprised to see a different side to Beach, a guy he calls “a big teddy bear” off the ice, and a young father to daughters Olivia and London. They’d visit Dad at the rink along with Beach’s wife, Keshia. “He was just so good around them,” Rattie says. “And even if it was a night he’d fought or whatever, he always just made things fun around the rink — he was never too serious, always joking around and stirring the pot, keeping things light.”

After practices at Allstate Arena, a lot of the younger members of the team would relax in a big hot tub on site, and Beach’s arrival was usually marked by a cannonball right in the middle of his teammates. Rattie laughs remembering how the team’s then-trainer, Kevin Kacer, suspended Beach from the tub more than once because the big enforcer’s entrances displaced so much water. “He was the kind of guy every team wants and needs to have,” Rattie says.

He was beloved on the ice, too, since Beach kept opponents accountable. “Back in those days in the AHL, you had a lot of bigger guys running around, and the fact that we had Cody Beach on our team, either to protect us, or guys would just be like, ‘I’m not gonna be stupid running around tonight because Cody Beach is out there,’ it was huge,” Rattie says.

Kurtis Gabriel fought Beach twice in the AHL, and says they were evenly matched. “But he was the type of guy who was just going to take on anyone — bigger, smaller, lighter, heavier, it didn’t matter,” Gabriel adds. “You definitely knew when he was on the ice, and I definitely knew going into games against him that I was going to answer for anything I did that he deemed not appropriate.”

While Beach spent parts of four seasons in the AHL, his professional career wasn’t consistent at that level. He was in and out of lineups, and bounced between the AHL and ECHL — from Chicago, to Kalamazoo, back to Chicago, and even to Alaska to play six games for the Aces before he was called to re-join the Wolves. During that Alaska re-assignment, Keshia packed the kids up and moved from Chicago to Moose Jaw, only to have to re-pack and return to Chicago a couple weeks later. “If I was my wife after that trip, I would’ve said, ‘This isn’t for me and you’re not for me anymore,’” he says, grinning and shaking his head. “But she didn’t. She stuck by my side, and we’ve made it this far. I’m really lucky.”

The season after his stint in Alaska, Beach was back playing with the Wolves when he took a hit and awkwardly went head-first into the boards. He had suffered concussions before, but this time, after two or three weeks of rest he still didn’t feel like himself. “I was living with a little bit of a headache every day, but getting the heartrate up would kind of make it unbearable,” he says. “I had light sensitivity, I wasn’t sleeping, and all this stuff was adding up to be just miserable.”

What Beach thought would be a few weeks off the ice turned into a few months. And then a few years. “I was living somewhat of a nightmare because all I wanted to do was be on the ice and be back with my teammates,” he says. “I was going through what some of the people do that have lost their lives over concussions.”

Were it not for Keshia, Olivia and London, Beach wonders whether he would’ve risked his health and continued to play with a head injury. Instead, he called it a career in 2016, at the age of 24. “I was fortunate to make that decision, because I had more to live for than myself,” he says.

After his retirement, Beach couldn’t even bring himself to watch hockey on TV, because he so badly wanted to be out there. He tried to lead what he calls “the normal life away from the rink,” selling farm equipment in Moose Jaw for a couple of years. “I struggled with it,” he admits.

His agent, Ross Gurney, had suggested to Beach that if he missed the hockey life, he should give officiating a try, a career change that worked well for one of Gurney’s other clients, Ryan Gibbons, who’s now an NHL linesman. In 2017, while he was still hawking tractors, Beach reached out to the director of officiating for the WHL, Kevin Muench, who’d had more than a few meetings with Beach back when he played in the league. “Five, 10 years before, he’s asking, ‘What are you thinking? That’s a big hit,’” Beach says. “And you go from those conversations, and then ask him to let you ref in his league.”

Beach figured he could jump right in at a high level, but Muench convinced him to build a foundation and work his way up. “He was a great student,” Muench says, “He really took the steps to be successful.”

Beach worked with the Saskatchewan Hockey Officiating Development Program, first taking the ice with six-year-old kids. The learning curve was steep, requiring him to figure out everything from how to skate without a stick, to where to stand as plays developed, even what to do between whistles. “It gave me a lot of gratitude, actually, to referees right away — a lot more gratitude than I had given them [as a player],” he says, laughing. “Because as I’m transitioning, I’m realizing there’s an art to it, there’s a lot more that goes into it than throwing a jersey on and putting your arm up and calling a penalty.”

“He was pretty rough around the edges to start,” says Dufour, the long-time WHL linesman who was one of Beach’s earliest officiating mentors. “As with many officials who are first starting out, he wasn’t very polished, his positioning on the ice wasn’t great, his anticipation wasn’t quite there. But those are all things you learn as you go, that come with experience. It wasn’t that he couldn’t do it, it was that he hadn’t figured it out yet. But he was willing to learn.”

In 2019, Beach was invited to his first WHL Officiating Camp, and he looked around the room and saw a lot of familiar faces from his playing days. When he stood up and introduced himself, he added, “If you refereed when I played, I’m sorry,” which got the room laughing. A lot of the officials there had separated Beach during fights, or talked him down from charging over the centre line to take on a guy from the opposing team during warm-ups (Dufour did that at least once). Later in Beach’s career, they’d even received a memo warning them to stop falling for his attempts to draw penalties by snapping his head back dramatically or whipping a hand off his stick, and instead start calling embellishment. “We called it the Cody Beach Rule,” Dufour says. “He was sneaky smart.”

And now, he was on the other side.

That same summer, Beach started tuning in to the NHL on TV again, because he didn’t want to miss former Wolves teammates like Jordan Binnington and Joel Edmundson on their 2019 Stanley Cup run with the Blues. “My heart was just fully back into the game, watching them and watching their emotions and seeing what they were able to accomplish,” he says, and it helped renew his dream to get to that stage himself.

Later that year, a still-green Beach attended the NHL’s Exposure Combine, a program designed to be a pipeline for former players who want to get into officiating. He calls the experience “completely eye-opening,” and jokes there was an ‘X’ beside his name — as in, “don’t hire this guy,” — after the first day. But the NHL’s director of officiating, Stephen Walkom, noticed Beach, and not only because he was a former pro and a good skater. “There were a lot of people like him at the combine, but you could see that he wasn’t just there for the experience,” Walkom says. “He was serious about going after this goal.”

Beach had conversations with the NHL officials there about what he needed to do to improve, and they told him to head back to Moose Jaw and continue to get more experience. “Cody really did that — he went back to his [adopted]hometown, and he just dug in,” Walkom says.

“The competitive spirit came out,” Beach adds. “I wanted to be a better ref tomorrow than I was today, and that really helped me, because that’s something I was kind of missing in my life too — I wanted something to be competitive with myself with. I was really fortunate to have a lot of people locally that could’ve said, ‘This Cody Beach guy, he was a goon and now he wants to be a ref and too bad.’ But I was fortunate that they really grabbed me and said, ‘Any help you need, we’re here for you.’”

Beach made his officiating debut in the WHL in 2020, and that year the director of scouting and development for NHL Officiating, Al Kimmel, watched him work a game in Saskatoon and was so impressed with his progress that he invited Beach back to the Exposure Combine in 2021. After his second experience there, Beach was awarded a contract that would see him work primarily in the AHL, with a shot at NHL games.

“He’s sort of discarded his player mentality, and now he has an officiating mentality,” Walkom says. “And you’ve got to really have a love for the game of hockey and want to stay in hockey so that you’re comfortable when you’re officiating, and natural doing it. And he had that natural knack for it.”

T

he morning after Kyle first shared his story with the world, Beach called him. Kyle was playing in Germany, and it was the first time the brothers discussed the experience Kyle says he had with the Blackhawks. The first words Beach said to his brother were: “I’m sorry.”

Beach is still sitting in a padded gold arena seat as he recalls the conversation, tears rolling down his cheeks. He felt he owed Kyle an apology “because I wish I would’ve asked more questions. I wish I would’ve been a support line for him. And I wasn’t. And I was naïve to think that everything was alright, or that it was a bad experience and he moved on from it,” he says. “Now, looking back, I put all the pictures together and something was never right. He was more distant with us as a family, he…” Beach pauses to take a few deep breaths. He wipes the tears from his face. “He wasn’t the hockey player that we all knew he was,” he continues. “And, looking back, you could just tell every day was tough. The signs were there and I didn’t ask questions, I didn’t support him, I didn’t help him.”

Beach told his brother all of this over the phone. He says Kyle immediately reassured him: “It’s not your fault.” Kyle said he was glad Beach hadn’t pressed him with questions on that rafting trip 10 years earlier, because he wasn’t ready to get into detail that day, only to share what he had.

“He got to the place in his life where he was willing and okay to talk,” Beach says, his voice shaking with emotion. “I wish we could’ve got this off of his shoulders years before, so he could’ve potentially still followed his dream and could’ve lived life just freely without that weight on his shoulders. I love my brother and I wish I would have had the courage to ask hard questions when I noticed things were a bit off. It may have saved years of depression and hardship — it may have saved his dream of playing in the NHL.”

Aldrich resigned from the Blackhawks the season after Kyle says he reported the assault and, as The Athletic’s Katie Strang reported, began working for USA Hockey. Aldrich later volunteered with a Michigan high school team, and in 2013, he pleaded guilty to the sexual assault of a 16-year-old member of that team. That player, according to reporting by Westhead, filed a lawsuit against the Blackhawks for providing positive recommendations for Aldrich to continue to work in hockey. Aldrich is now a registered sex offender in the state of Michigan.

“Obviously I believe things should have been handled very differently, but we live and we learn and we become better for it,” Beach says. “When you’re in the hockey community, we always think ‘hockey, hockey, hockey,’ and I feel sometimes it’s forgotten that there is a bigger picture: We are human beings and we need to take care of one another, first and foremost.”

Beach admits to wondering, as he got closer to achieving his renewed NHL dream, whether his brother’s lawsuit against the Blackhawks and criticism of the league would impact his officiating career. But he says he got support from the NHL to step away whenever he needed, to spend time with family and his brother, that he’d be welcomed back if he needed time away. He didn’t end up taking time off.

Beach takes a deep breath as he considers the impact Kyle has had on the game and on others who’ve experienced sexual violence, and marvels at the strength his older brother displayed. He thinks about what it must’ve been like to be a first-round NHL draft pick with high expectations and never get to skate in a regular-season NHL game. He thinks about the emotional fallout of sexual assault, and all the weight Kyle must have carried alone for so many years. The brothers still have a competitive relationship today, but one thing is clear to Beach.

“I won’t tell him to his face, just because of our relationship, but to me, he’s a hero,” Beach says, as tears roll down his cheeks. “He’s my hero.”

I

t was April 12, 2022, and the Arizona Coyotes were playing host to the New Jersey Devils. Beach was set to make his NHL debut, and while he tried to prepare for the moment as best as he could, it didn’t hit him that he’d truly made it until his blades hit the Gila River Arena ice. “That’s when I realized that I had this dream as a kid — I was three years old playing mini sticks and stuff with my dad and brother and envisioning playing in the NHL, and then having that dream cut short, and finding another path,” he says. “It all came full circle and I was full of excitement and almost gratitude towards the sport in being able to find another way to make the dream of that little kid come true.”

Beach has since refereed three other NHL games, and his contract this season is similar to the two-way a player would have. “His progression is right where he needs to be,” Walkom says. “I know that Cody has his focus on conquering the AHL this year and making the most of his opportunities when he gets the chance to work in the NHL.”

If you ask Gabriel, who twice fought Beach, the former enforcer is one of the most consistent referees in the AHL. “For me, it makes total sense for him to be doing that job,” says Gabriel, who retired in September after logging 51 games in the NHL and 371 in the AHL. “Guys like us like to play the game fair and with justice. He’s been there, he’s been someone who’s yelled at refs and was pissed at calls, too. For someone who hasn’t been [officiating]too long, he’s got a very solid reputation. He doesn’t make the game about him, which I really like. I don’t think many refs are going to have a great reputation, because again, you’re a ref, but just to see someone who you don’t have much to say bad about, that’s as respectable as it gets, you know?”

Beach has progressed from officiating six-year-olds to AHLers and NHLers in just five years. But what could be seen as a breakneck ascent instead looks, from his perspective, like a steady build. “From Day 1, as soon as I put on the jersey, I looked at it as a full-time job, as another opportunity to get where I wanted to get to,” Beach says. “I think if you do that and you’re thinking the game 24 hours a day, in your sleep, that preparation and all that time and effort will lift you and kind of skyrocket your trajectory.”

Stothers can’t wait to see Beach officiate a Ducks game, in part because he wants to razz his former player to keep up with the pace of play, but also because he’s proud of Beach for forging this new path. “Beacher was passionate that he wanted to be in the hockey life,” says Stothers, who was drafted to the NHL himself and played 30 games. “Sometimes it’s not the right time, it’s not the right team, you’re not the right fit. But he stuck with it and he found a way to still be at the rink and enjoy the love of the game that he has — he’s just looking at it from a different perspective.

“It’s great for him and it’s great for hockey. I think there’s a respect from the players when they look up and they see a guy that played himself and went through the trenches to do it the hard way like Cody did. Nothing was ever given to Cody. The fact that he stuck with it, that’s a tribute to him.”

But why did Cody Beach stick with hockey? After everything he’s been through, after learning his brother’s whole story, how could he put on the uniform and get back out on the ice?

Beach acknowledges that both he and Kyle could’ve walked away from hockey given the pain it has caused. “I think it comes back to just, we love this game,” he says. “For me, it was really hard to see a family member — especially my brother, who I idolized growing up — be involved in such a heartbreaking incident. But ultimately with his story and some others, it has helped the hockey community look at our culture and address how we can all be better within the game, outside of the ice surface.”

An independent investigation was conducted into Kyle’s reports of sexual violence and the Blackhawks’ response, with findings released in an October 2021 report. It revealed the team’s leadership discussed the reported sexual violence at a meeting in May 2010. The report also states that GM Stan Bowman recalled both president John McDonough and head coach Joel Quenneville expressing “a desire to focus on the team and the playoffs.” Leadership didn’t report Kyle’s experiences to human resources until June 14, five days after the Blackhawks won the Stanley Cup. The club’s director of human resources offered Aldrich the option to resign or undergo an investigation. Aldrich resigned on June 16. He received severance, a playoff bonus, and his name was engraved on the Stanley Cup.

In the wake of the 2021 report, Bowman, Quenneville and senior VP of hockey operations Al MacIsaac all resigned. McDonough was fired prior to the report’s release. The team’s assistant GM, Kevin Cheveldayoff, is still working in the NHL as GM of the Winnipeg Jets. NHL commissioner Gary Bettman told reporters that Cheveldayoff “was not a member of the Blackhawks senior leadership team in 2010, and I cannot, therefore, assign to him responsibility for the club’s actions or inactions.” NHLPA executive director Donald Fehr apologized in a statement and said the lack of action on the union’s part “was a serious failure.” Fehr remains head of the NHLPA.

The NHL fined the Blackhawks $2 million for “the organization’s inadequate internal procedures and insufficient and untimely response.” More than a decade earlier, the league fined the Devils $3 million for circumventing the salary cap in an attempt to sign Ilya Kovalchuk — the most recent comparable fine doled out to a club, according to Sportsnet’s Stats and Information Department.

In December 2021, shortly after the investigation was published, Kyle and the Blackhawks reached a confidential settlement.

While there has been plenty of criticism from fans and media directed at both the NHL and the Blackhawks as details have emerged, Beach says his own personal experience with the league has been a positive one. He views the NHL as a leader when it comes to bettering the game, and believes lessons are being learned and applied to improve hockey.

And despite everything the Beach brothers have been through, the younger Beach believes they now have more to offer hockey than ever before, that their experiences make them stronger in their current roles. For Kyle, that’s as the coach of the Trinity Western University men’s team in B.C., a job he began this season. “I couldn’t be more excited for him to pass on not only his extremely talented hockey mind, but also to be able to draw on his life experiences to support and build up other young men,” Beach says. “For me, it was extremely difficult having to pivot from hockey player to real life, but it also gave me a lot of perspective and appreciation for how lucky I was to be embedded in something I loved from such a young age, which ultimately helped push me to take on the challenge of pursuing officiating.”

With NHL experience under his belt already, Beach is more determined than ever to earn further opportunities on that stage. “You get that craving and you just want to do more and more,” he says. “The atmosphere is what made me come back to finding something in hockey. You can do anything else you want but once you get to the rink and the fans are on top of you — that’s what we live for, as players and refs.”

Eight hours later, when Beach walks through the Zamboni tunnel at ice level at Scotiabank Arena, he’s got a broad smile on his face. He doles out a fist bump, then snaps his helmet’s chinstrap shut before he takes a few running steps toward the ice. He skates a few quick laps while music blares from the arena’s speakers and fans continue to file into their seats. As the Canadian national anthem is sung, he shuffles from skate to skate in anticipation of puck drop.

In the third period, Beach drops that puck himself at centre ice. Later, he calls a cross-checking penalty, miming the action as he spells the minor out for fans.

Here he is, skating on an NHL sheet, just as he always dreamt he would one day. Reaching this moment involved more pain and heartbreak than he ever could’ve imagined. It took a complete reinvention. But Beach remains focused on the present and the future, on this next opportunity in hockey. “You don’t always get a second chance,” he says.

Tara Walton/Sportsnet (6)