Today, Beijing is a superpower, but it only has to look over its northern border for a cautionary tale

The events of the late 1980s and early 1990s had a major impact not only on the development of Russia and China, but also on the dialogue between the two countries. Moscow and Beijing abandoned decades of rivalry and opted instead for pragmatic cooperation.

In 1989, the Soviet Union, where the liberal winds of perestroika were blowing at the time, supported the actions of the Chinese authorities in firmly suppressing the Tiananmen Square protests. And in 1991, despite their ideological sympathies for the USSR’s leadership, the Chinese Communists expressed their willingness to work with the new Russian government under Boris Yeltsin.

Over time, Russia and China have evolved into de facto allies, and their relations are described today as “the best ever.”

Meanwhile, the collapse of the USSR gave the Chinese much food for thought – not so much about the fate of the Soviet Union, but about their own future. It is no exaggeration to state that an analysis of what happened in the USSR has, in a certain sense, determined the vector of China’s development.

The example of what transpired in Moscow has served as a warning against hasty political reforms and the removal of the party from the leadership of the state and army. Under Xi Jinping, studying the Soviet experience has become an important part of the party’s propaganda, because, for Chinese observers, the main thing that happened in 1991 was not the collapse of a massive state, but the loss of power by the Communist Party of Soviet Union (CPSU).

The death of an older brother

The attention paid in China to the events in the USSR should come as no surprise. Throughout the entire period of the existence of the Communist Party of China (CCP), the Soviet Union has served as a reference point for its leadership and a significant factor in making various domestic political decisions.

The CPC itself was set up in 1921 in the image of the CPSU, and established with the direct participation of emissaries from Moscow. Many CCP leaders had studied in the Soviet Union and spoke Russian. Military, technical and financial assistance from Moscow was crucial during the CCP’s war with the Kuomintang and throughout the 1950s, until the two countries began to quarrel over ideological differences.

Despite the disagreements, the experience of the USSR has been closely studied at all levels. Particularly since the beginning of perestroika when discussion of the reforms in the USSR took place in the media and in university classrooms. There was a great deal of interest in the personality of Gorbachev on the part of student activists.

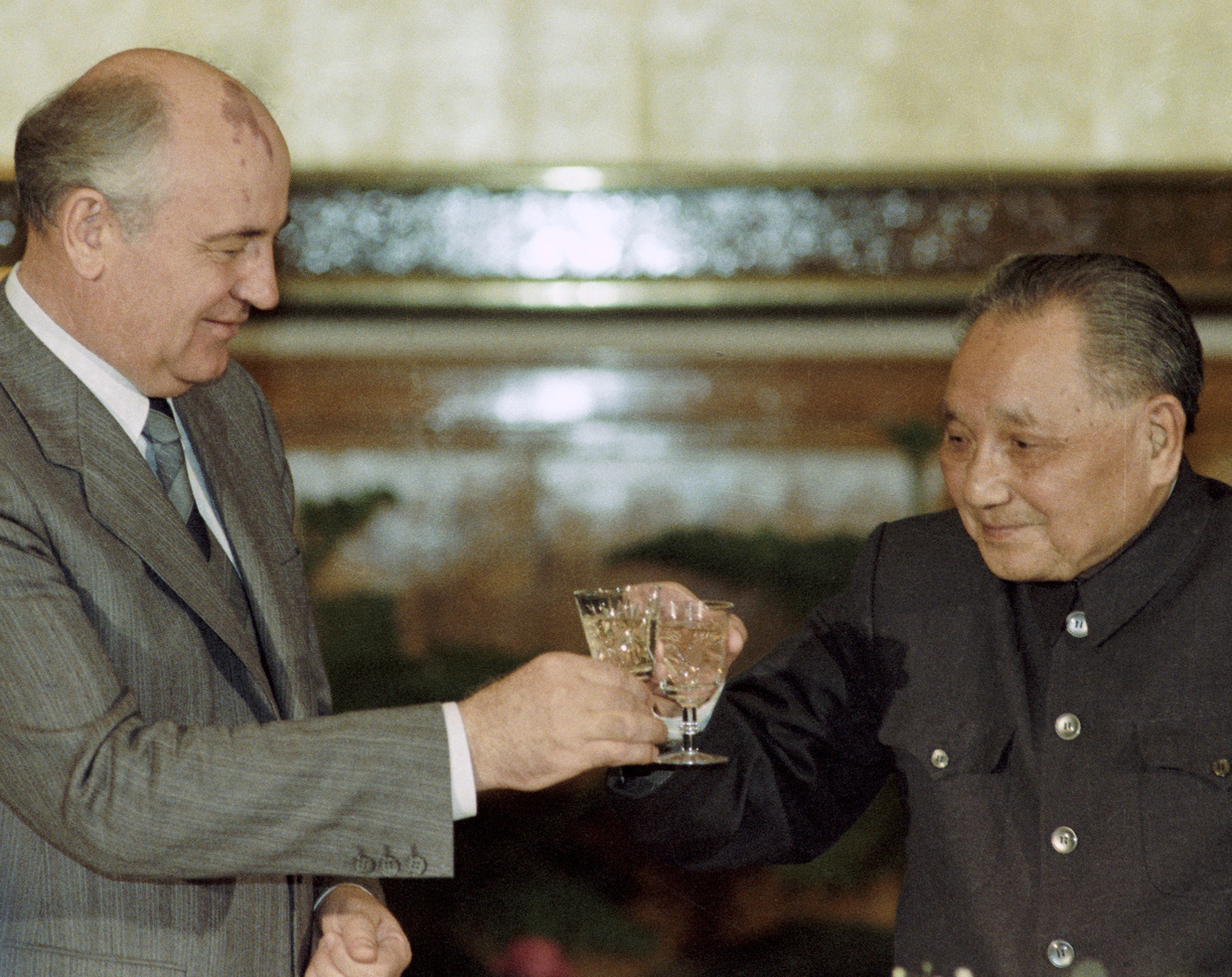

The Soviet-Chinese summit in Beijing in May 1989 escalated the “Tiananmen crisis” precisely because relations with Moscow and Soviet leaders’ reactions to events in Beijing were very important to Chinese leaders.

In China, it was believed that in the Soviet Union, a sit-down hunger strike in the country’s central square, during a major visit by a foreign leader, was simply not possible. As proof of this, examples were given of the violent suppression of demonstrations in Alma-Ata, Minsk and Tbilisi. The fact that the CPSU would disband in two years and that the situation in the USSR would be out of control was unthinkable in Beijing at the time, as an analysis of the available documents shows that the events of 1991 came as a complete surprise to the Chinese.

© Sputnik/Runes

By then, however, China’s political reforms had already been frozen. This was facilitated not only by overcoming its own political crisis, but also by observing the revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe. Faced with the threat of being ousted from power, China’s elites consolidated, and it was assumed that the CPSU would do the same. During the August putsch against Gorbachev, Beijing’s leaders spoke positively about its hardline leaders, and the Chinese ambassador in Moscow congratulated the members of the junta for coming to power.

The suppression of the putsch and subsequent self-dissolution of the CPSU was perceived by Chinese leaders as a severe blow to themselves as well. Deng Xiaoping feared that the party would be banned and the CCP would remain the only major Communist party in the world, after which the West would come down hard on it. In the autumn of 1991, the first papers published in China portrayed the events in the USSR in a negative light, and the Central Party School even set up a separate group to counter the “peaceful rebirth,” denoting the danger that had befallen the CPSU.

Who is to blame and what to do

The Belovezha Agreement and the collapse of the Soviet Union were quickly perceived solely as the logical results of the collapse of the ruling party. Beijing showed its willingness to work with the new post-Soviet states however, establishing diplomatic relations with most of them as early as December 1991.

In China itself, the topic of studying the “Soviet crisis” took on a life of its own, first as a major theoretical and then as a practical problem. While at the first stage the study was limited to a banal search for blame (“it’s all the West’s fault” or “it’s all Gorbachev’s fault”), Chinese scholars later moved on to a systematic, comprehensive, interdisciplinary analysis.

In all, Chinese scholars have written more than a hundred scholarly works on the collapse of the CPSU and the USSR, not counting various essays and conference papers. Among them are several voluminous monographs authored by Russia-focused historians, as well as economists, political scientists and specialists in Marxism-Leninism. The interest of the scholars is easy to explain, as it pursues very concrete goals, which have not lost relevance for the PRC. Chinese experts must answer two key questions: 1) what were the causes of the collapse of the USSR and the CPSU, and 2) what should the CCP leadership do to avoid their fate?

Among the main reasons for the collapse, according to the Chinese studies, were those associated with the weakening of the party. Namely, the pervasive corruption, the detachment of the its elite from the common people, the emerging consumerism, and the formalism and bureaucratic tendencies of party ideologues and agitators, which led to a total disbelief in the policies imposed from above.

© Sputnik/Vladimir Rodionov

Chinese scholars have been rather harshly critical of the structure of the Soviet economy, above all its centralization, which dates back to the position of Mao Zedong in the 1950s. Another problem for the USSR was the bias towards the military-industrial complex and heavy industry, which led to acute shortages of consumer goods. Although there is little criticism of the economic content of the perestroika agenda in Chinese authors, it is noted that the efforts of Soviet reformers were belated and ill-conceived, and thus failed to address numerous social problems.

However, as the Chinese point out, the Soviet Union was forced to carry out reforms amidst a still ongoing confrontation with the West – and powerful cultural and informational pressure from the outside – which against the background of the crisis in the economy and political system caused a strong “faith deficit” in the ruling party, ideology and broader country. Chinese scholars credit Mikhail Gorbachev with moving away from a costly confrontational line in relations with the West, but believe that the moment for change was already lost and the USSR paid the price in the 1980s for a long period of striving for global hegemony. In fact, Gorbachev’s turn in foreign policy only strengthened the penetration of Western influence in the USSR and helped America to defeat its rival.

Given that China itself now finds itself in the position of “major rival to the West,” the study of the “Soviet lesson” takes on particular significance.

“Soviet Lesson”

The study of the CPSU’s mistakes moved from the offices of academics to classrooms for party members, and then to the national level. In 2003, the Politburo of the CPC Central Committee held a collective study session to examine the rise and fall of nine great powers in world history, including the USSR. In 2006, based on the materials of that session, a six-part film ‘The Collapse of the CPSU and the Collapse of the USSR: Memoirs of Eyewitnesses’ was broadcast on China Central Television. That same year, the Institute of Marxism of the Academy of Social Sciences produced a film ‘Think Danger in Times of Peace: Historical Lessons of the Collapse of the CPSU.’ Six years later, the subtitle of that film became the title of a multimillion print-run book: ‘The Collapse of the CPSU and the Collapse of the USSR.’

A new surge of interest in examining the mistakes of the CPSU is associated with Xi Jinping’s accession to power. It appears that he himself is deeply preoccupied by its collapse. References to the event have featured in speeches and publications throughout the Chinese leader’s tenure. A recent article by Xi for the party magazine Tsushi says: “The Russian Communist Party seized power with 200,000 members, defeated Hitler with two million members and lost power with nearly 20 million members.” This happened, according to Xi, because “ideals and convictions disappeared” and “no one came out to defend the party with arms in their hands.”

The same idea, reference to Xi Jinping’s views, was expressed in one of a series of documentaries devoted to the 20th CPC Congress entitled ‘A Strong Country Should Have a Strong Army.’

This thesis is repeated in virtually all materials devoted to the forthcoming centennial of the People’s Liberation Army of China (to be celebrated in August 2027), including Xi Jinping’s concluding speech at the 20th CPC Congress.

To summarize, Chinese discourse has firmly established the notion of the collapse of the CPSU and the collapse of the USSR (in exactly that order) as an important lesson for Beijing. Meanwhile, the crisis in the Soviet Union by the mid-1980s is described as having been systemic in nature. The social and economic transformation of the USSR and the reforms within the CPSU were necessary in the Chinese view, and therefore entirely justified. But they were overdue, and could no longer solve the problems associated with the lack of public confidence in the authorities and the decay within the party.

The party’s misguided policy of disengagement from state administration and the military, in the eyes of the Chinese, is of key importance. Appealing to the negative experience of the CPSU-USSR is actively used by the CCP leadership in propaganda as an argument in favor of the impermissibility of any reforms related to the weakening of the role of the party in the life of society.