MONTREAL — Ken Dryden stood six-foot-four but cast a much larger shadow. He was a titan of sport and a goliath in life — the only six-time Stanley Cup winner to backstop Canada to some of its greatest wins on the ice before serving Parliament off it.

Dryden, the great goaltender of the dynastic Montreal Canadiens of the 1970s, died Friday of cancer at age 78.

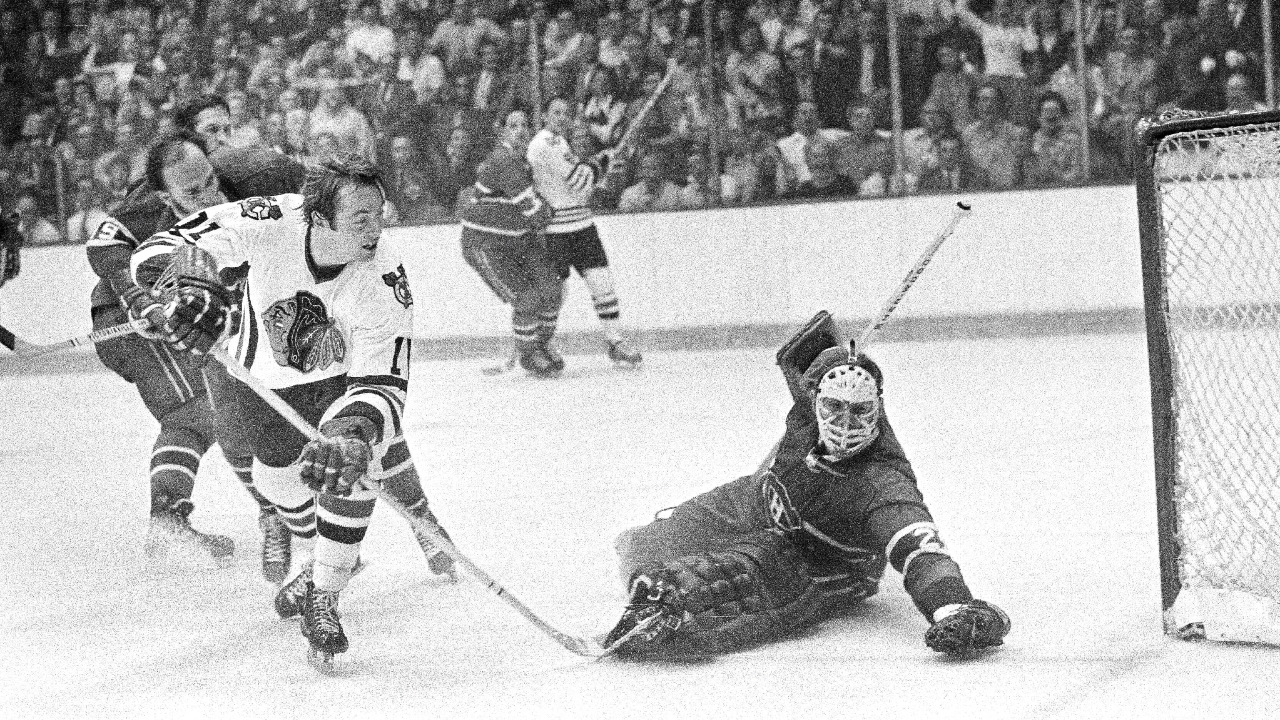

But the iconic image of him standing in his crease, leaning on his stick, will live on forever.

It is the image that personified him. The image of a man so confident and composed that he could relax as chaos whirled all around him. In this image, he is Ken Dryden: the thinker. In this image, he is also Ken Dryden: the admirer of what he considered the greatest show on ice, which he reviewed thoroughly in what might be the most captivating sports book ever penned, “The Game.”

In it, Dryden wrote, “When you are a presence, there are many things you need not do, for it is simply understood you can do them.”

Those words resonate deeply as a nation mourns his passing.

Dryden established a mammoth presence from the minute he stepped into the Canadiens’ crease in the spring of 1971 to the minute he took his last breath on Friday.

The on-ice accolades — four of six Cups earned consecutively, a Conn Smythe win before capturing the Calder Memorial Trophy a year later as the NHL’s most outstanding rookie, five Vezina Trophy wins, the victories over the USSR in the 1972 Summit Series — made Dryden one of the most prolific athletes of all time. He did it with great athleticism and flair and, above all else, efficiency.

My father would say Dryden made the saves you expected him to make, but also made the ones you didn’t expect him to make look easy. The footage, which will undoubtedly be exhumed on YouTube as tributes to his sterling career pour in, confirms it for anyone who wasn’t alive to watch him play in real time.

Dryden was spectacular, and then he was done. He retired after just eight seasons and left the game while still seemingly at the height of his unparalleled abilities. It’s one of the things that made him one of a kind in the world of sports.

There were many more that made him unique in general.

The Toronto native spoke English and French, and in paragraphs instead of sentences. He first studied law and later taught it. He presided over the Maple Leafs, and then over a massive mandate as minister of social development in Prime Minister Paul Martin’s Liberal Party government of the early 2000s. And, in his spare time, he wrote books and articles about hockey.

Dryden didn’t just write and talk a lot. He was also a man of action, most admirably using his gigantic presence to often act as hockey’s conscience.

“The Game” was a gift to all sports fans — and especially Canadiens fans — but “Game Change: The Life and Death of Steve Montador, and the Future of Hockey,” a book about the tragic consequences of concussions, was advocacy for prudence and humanity in an unforgiving and, by nature, violent sport.

Dryden was deeply principled, and everyone knew it. People simply understood he would always speak and act on his convictions. They learned that when Dryden stepped away from hockey right as he was making his meteoric rise in the sport to pursue his law education by articling for a Toronto firm in 1973, and they came to expect it from him as his presence and profile continued to proliferate.

Dryden was tall, and he was thought of as someone who stood tall — both in his crease and outside of it.

He is survived by his wife, Lynda, and their two children. And he will be remembered by the public for his heroics in bleu, blanc et rouge and red and white, and for his incredibly poignant thoughts on hockey and sports.

Like this one, on the impossible standards demanded of professional athletes, from “The Game”: “We are allowed one image, one angle; everything must fit. So normal in one thing begins to look like normal in the rest. Unlike the Greeks, who gave their gods human imperfections, for us every flaw is a fatal flaw. It has only to be found, and it will be found.”

Or like this other one, about the short career span of a professional athlete, also from “The Game”: “If it is true that a sports career prolongs adolescence, it is also true that when a career ends, it deposits a player into premature middle age. For, while he was always older than he seemed, he is suddenly younger than he feels. He feels old. His illusions about himself, fueled by a public life, sent soaring then crashing, have disappeared just as those of contemporaries have come to full bloom.”

Dryden didn’t appear old or infirm when I saw him at the Bell Centre in December of 2024. And at least one former teammate of his with the Canadiens, who was too devastated to speak about his life Saturday, called his death “unexpected.”

It is a massive loss for the hockey world, for the Canadiens, for Canada, for everyone who knew him, and for countless others who didn’t.

But that image of Dryden with glove and blocker perched over stick is eternal.