A team of researchers are peering into what the solar system may have looked like in its earliest stages, unlocking answers about the formation of amino acids – and ultimately life as we know it – by analyzing ancient space rocks.

The new findings – reported by an international group of scientists led by the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) – were published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal.

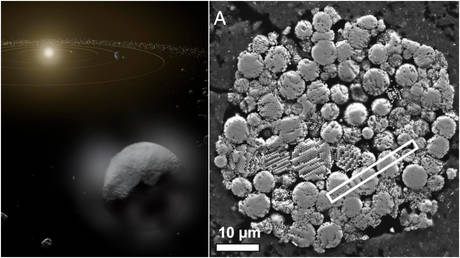

Performing an atom-by-atom analysis of the Tagish Lake meteorite that spectacularly arrived on Earth back in 2000 the team was able to get an idea of what the nascent solar system was like millions of years ago. Using atom-probe tomography, which is capable of imaging atoms in 3D, the scientists discovered water precipitates left in the meteorite’s magnetite grains.

“We know water was abundant in the early solar system,” Dr Lee White, the lead author of the study, explained.

The Tagish Lake boulder – named after a body of water in Canada –largely disintegrated upon its entry into Earth’s atmosphere, yet some 10 kilograms of its remains were collected from the frozen lake. The research suggests fluids found in the space rock were sodium-rich and alkaline – or near-ideal conditions for the synthesis of amino acids, which are a key component of life.

“Amino acids are essential building blocks of life on Earth, yet we still have a lot to learn about how they first formed in our solar system,” said Beth Lymer, co-author of the study and a PhD candidate at York University.

The study found that, given the composition of the fluid, amino acids could have rapidly formed on the meteor, possibly planting the seeds for microbial life as far back as 4.5 billion years ago.

Like this story? Share it with a friend!