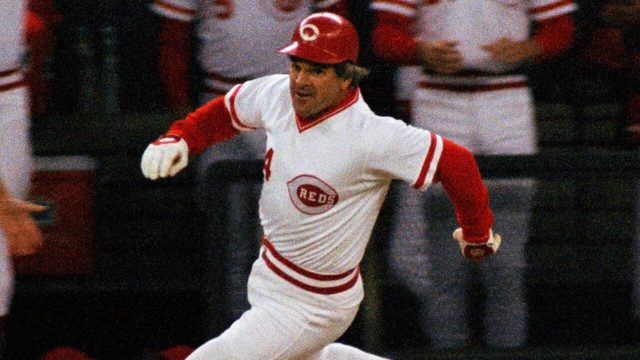

In Tampa, Fla., during the summer of 1961, a switch-hitting 20-year-old began his first full season as a professional baseball player. Playing for the Cincinnati Reds’ Class-D affiliate, Pete Rose made an instant impression.

At the plate, Rose hit .331 with 30 stolen bases and — most remarkably — 30 triples. As manager Johnny Vander Meer said at the time, “He runs like a scalded dog.” But even then, the speed that allowed Rose to leg out those extra bases was somehow secondary to his distinct style of play. “Hitting and speed are not his greatest assets,” Vander Meer said. “I’ve seen a lot of players who had all the tools to be great, but they weren’t aggressive. Rose is aggressive every minute of every day. He’s aggressive when he’s batting, running or playing the infield.”

Or even simply drawing a walk. In 1963, Rose sprinted to first after earning a base on balls in a spring training game — the ultimate display of intensity. Irked, Yankees pitcher Whitey Ford nicknamed him Charlie Hustle. It stuck.

Rose died Monday at the age of 83. But over the course of a career that spanned 24 seasons and featured three World Series wins, he collected more hits than any player ever. Of course, that’s just the beginning of the story for Rose, who received a lifetime ban from MLB for betting on baseball while he was still an active manager. And while Rose debated the specifics of those bets for years, repeated appeals for reinstatement left him on the outside looking in for the rest of his life. Adding further to the questions about Rose’s character, there are allegations he had a sexual relationship with a minor in the early 1970s. So, baseball’s all-time hit leader does not have a plaque in Cooperstown alongside baseball’s other greats, and today he’s known as much for his off-field infamy as on-field excellence.

Born in Cincinnati in 1941, Rose played football and baseball starting at a young age. The draft didn’t yet exist when he was growing up, so Rose landed a pro contract with his hometown Reds thanks to the recommendation of an uncle who scouted part-time. Right away, it became apparent that the team had stumbled onto a special player.

Whether you liked him or not, Rose could play. He won Rookie of the Year in 1963, but it wasn’t until his third big-league season that he really settled in. In 1965, he hit .312 and made the first of 17 all-star appearances. By then, Rose was emerging as a star, and he’d keep playing like one for years. While some players peak for three or four seasons, Rose’s prime seemed to last forever.

Over the next decade and a half, he would average 204 hits per season, hit at least .300 in 14 of 15 years, and win three batting titles. He’d earn MVP votes in all but one of those seasons and win the award once, in 1973. From 1965 to 1979, only one player in baseball generated more wins above replacement than Rose: his long-time Reds teammate, Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Morgan.

For many young baseball fans of that era, Rose represented intensity, focus and work ethic. In 1976, soon after struggling through his first minor-league season, an 18-year-old Pat Tabler was running errands in his hometown of Cincinnati, where Rose happened to be finishing up an autograph session.

Tabler’s mind started racing. He had met Rose once before at a pre-draft workout at Riverfront Stadium. That was months ago, though. Since then, Rose had won another World Series with the Big Red Machine. All Tabler had done was hit .231 with 12 errors and one home run at low-A ball. So as the crowd around Rose dispersed, it was with a mixture of excitement and trepidation that Tabler approached the three-time batting champ.

“Hey Pete,” Tabler said.

Rose responded without hesitation: “Hey Pat, how’re you doin’?”

Soon enough, they were talking baseball. “I was on cloud nine,” Tabler recalled in 2020. “For a Cincinnati kid, that’s like, ‘Is this really happening?’”

“I’m like, ‘I want to join this fraternity,’” said Tabler, who would go on to play 12 big-league seasons. “’I want to be a part of this. What do I do? I’m going to work my ass off.’”

Meanwhile, Rose’s intensity drove him forward, one head-first slide at a time. But there was a cost to that no-holds-barred style, and it was never more apparent than at the 1970 All-Star Game. With two outs in the bottom of the 12th inning, Rose was on second base representing the winning run. A single to centre field offered him the chance to score and he took it, rounding third at full speed and barrelling into Cleveland catcher Ray Fosse, exhibition game or not. Rose scored, and the National League won, but Fosse fractured and separated his shoulder in the collision. He would never again replicate the offensive numbers he posted that year.

With Rose, Morgan, Johnny Bench and Tony Perez all in their primes, and manager Sparky Anderson at the helm, the Big Red Machine was a force to be reckoned with. And not only did Rose produce at the plate in 1975 — he also changed positions, moving from left field to third base. The Reds won 108 games that year before winning the World Series. Rose was named series MVP. The next year, they won 102 games, then swept the Yankees in the Fall Classic. By then it was clear this was one of the greatest teams ever assembled.

“Somebody’s gotta win and somebody’s gotta lose,” Rose once said. “I believe in letting the other guy lose.”

In 1980, Rose would win a third World Series, this time as a first baseman with the Philadelphia Phillies. The Phillies had signed him to a four-year, $3.2-million contract a season earlier and the investment paid off with the Series win despite a relatively modest campaign from the 39-year-old Rose.

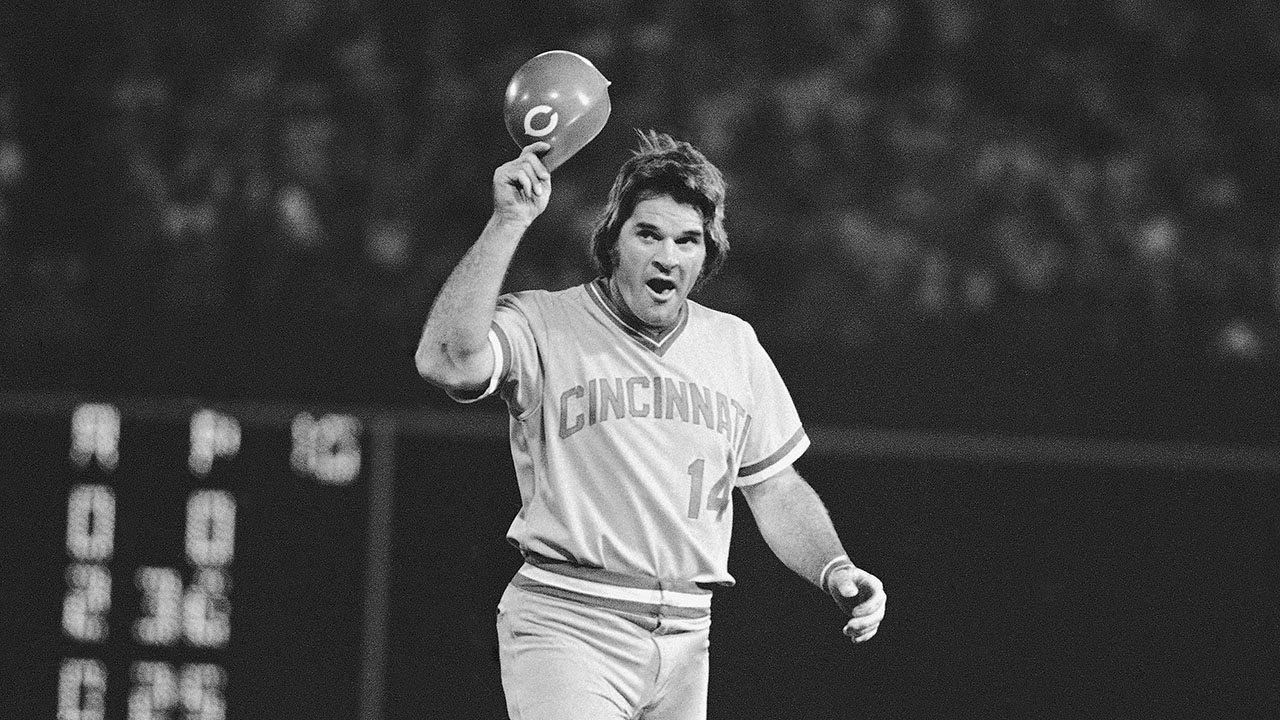

But even as Rose’s production declined, he kept playing — and kept piling up hits. In 1978, at the age of 37, he put together a 44-game hit streak. In 1981, at the age of 40, he batted .325, the last of his 15 full seasons at .300 or better. In 1985, at the age of 44, he put himself in the lineup for 119 games in his new role as a player-manager, and made his final all-star team.

“Doctors tell me I have the body of a 30-year-old,” Rose said at the time. “I know I have the brain of a 15-year-old. If you’ve got both, you can play baseball.”

Late that season, Rose closed in on a seemingly unbreakable record. In a sport where 3,000 hits all but assures players a place in Cooperstown, Ty Cobb’s all-time career record of 4,191 appeared sure to stand forever. But on Sept. 11, 1985, Rose hit a single to centre field for hit No. 4,192 (Tabler, by then a veteran of five big-league seasons, happened to be home in Cincinnati dealing with an injury that day; he went to the game to watch Rose and still has the ticket stub). By the time Rose stopped playing the following year, he had 4,256 hits to his name, a record that no one has approached since.

Yet as the years went on, Rose’s personal and professional integrity would face great scrutiny. By 1989, allegations about his betting habits had started to surface. Rose, who had managed the Reds from 1984 through 1989, was betting on horse racing and other pro sports at the time. So, many started to wonder, did he bet on baseball?

MLB commissioner Bart Giamatti hired lawyer John Dowd to investigate. The report Dowd produced alleged that Rose had placed 412 baseball bets in 1987, including 52 on the Reds to win. Not only did Rose deny these allegations and refuse to appear at a hearing, he initially filed a suit arguing that Giamatti couldn’t provide a fair hearing. It wouldn’t be the last time Rose and Dowd would find themselves at odds.

But on Aug. 24, 1989 , Rose accepted a spot on baseball’s ineligible list with an understanding that he could apply for reinstatement a year later. In a public statement issued that day, Rose neither admitted to betting on the Reds nor denied it, but he acknowledged that Giamatti “has a factual basis to impose the penalty.”

“The banishment for life of Pete Rose from baseball is a sad end of a sorry episode,” Giamatti said. “One of the game’s greatest players has engaged in a variety of acts which have stained the game, and he must now live with the consequences of those acts.”

A week later, Giamatti died of a heart attack.

That same year, Dowd, the lawyer Giamatti hired to investigate Rose in 1989, alleged during a radio interview that Rose committed statutory rape when he was a player. Rose filed a defamation suit against Dowd, and the sides would ultimately settle out of court. Yet a woman identified as Jane Doe testified that she had had a sexual relationship with Rose starting when she was 14 or 15 and he was in his mid-30s, married with two children. Rose acknowledged having had a sexual relationship with her, but said it started when she was 16 — the age of consent in Ohio at the time. Amid those allegations, FOX Sports parted ways with Rose, who had been a national TV analyst from 2015 to 2017.

Asked about the allegations by female reporter Alex Coffey of the Philadelphia Inquirer in 2022, Rose replied: “It was 55 years ago, babe.”

Over the years, Rose consistently denied that he bet on baseball. Whenever a new commissioner took over, he’d apply for reinstatement, but without contrition. In 2004, he finally admitted to betting on baseball within his book, My Prison Without Bars. “It’s time to take responsibility, and I’m 14 years late,” he said at the time .

“I bet on my team to win every night because I love my team. I believe in my team,” Rose later told ESPN. “I did everything in my power every night to win that game.”

MLB decision-makers did not appear convinced. When Rose applied for reinstatement again in 2015, commissioner Rob Manfred denied the request, explaining that Rose’s comments “provide me with little confidence that he has a mature understanding of his wrongful conduct, that he has accepted full responsibility for it, or that he understands the damage he has caused.”