One in four adults in the U.S. are living with a disability, but you wouldn’t know it given the lack of representation in the workforce, Hollywood, and media coverage. On the 30th anniversary of the Americans With Disabilities Act, Voices of Disability celebrates the real stories — not the stigmas or stereotypes — of this dynamic and vibrant community of individuals.

When YouTuber Annie Segarra first started using a wheelchair, finding clothing that fit their style was a challenge. “In the past few years, my physical disabilities started to dictate what kind of clothes I could wear and that has been a little tricky to navigate,” says Segarra, who wanted to find a balance between satisfying their aesthetic and accommodating their identity. And when they came upon posts about queer crip fashion on Tumblr, they began to feel empowered to find new ways to express themselves.

Queer crip fashion is a rising dress movement catering to those whose gender, sexuality, mental, and/or physical ability typically do not fit in with what white supremacist, heteropatriarchal, normative society deems acceptable. It’s fashion rooted in disability justice that takes into account every single aspect of a person. It goes beyond queerness and disability, too: It’s slow, ethical fashion that’s often customized to fit an individual’s specific needs; it’s about challenging norms around the body and identity.

“Everyone deserves to have clothes that fit them, are comfortable and easy to wear, and that celebrate who they are,” says Edmund Green Langdell, a designer based in New York. The designer makes accessible, gender-affirming clothing, including chest binders and tucking or gaff underwear, which is meant to hide genitalia. Core to his work is the belief that the diversity of all bodies, abilities, genders, races, and sexualities among humans must be reflected by the fashion industry.

“When I think about what queer crip fashion is, I think it’s fashion grounded in access and it challenges regimes of normalcy,” says Ben Barry, chair of fashion at Ryerson University in Toronto where students are encouraged to design for all bodies. “It’s completely refusing the fashion system and how it has been set up by dominant, Western, white culture.” Barry says in lieu of commercially available options, clothing has long been “hacked” and made more accessible by individuals and their families. While the movement may feel recent for outsiders, the queer crip community has always existed—as has its need for accessible fashion options.

For too long, the fashion industry has ignored these identities, especially the intersections of them. But some brands, including Chromat and Savage x Fenty, have started to change the script by featuring disabled models in their runway shows. There’s also Tommy Hilfiger’s inclusive line Adaptive; the recurring disability-friendly collection launched in 2018 with the aim of empowering people of all abilities to express themselves through fashion. Models like Jillian Mercado, Chella Man, Lauren Wasser, and Mama Cax (who passed away in December 2019) have all helped push the industry forward, using their platforms to address the challenges of navigating the fashion industry as disabled individuals while advocating for better treatment and increased visibility.

While the cultural zeitgeist is shifting slowly, a small group of creatives are taking matters into their own hands and designing clothes that meet unique needs as well as advocating and building a community for people who identify as queer crip.

Part of that is educating people on what, exactly, it means to have a disability. “What is problematic is when people say,‘I don’t see your disability,’” disability fashion stylist Stephanie Thomas shares. “We are not a monolith.” Thomas styles disabled models and actors as well as consults tech companies on how to better understand the disabled community via language and marketing tactics. “I try to empower people with disabilities like myself, to dress with dignity and independence and to have fun doing it.”

Education is the bedrock of change and fashion has the power to shift how we view people’s abilities and identities. It’s time to dispel all myths about what it means to be a person who’s disabled, and a person who is queer, by normalizing and making seen what has long been strategically hidden from public view.

THE VALUE OF RADICAL VISIBILITY

After taking a leave of absence from university due to gastroenterological issues, non-binary creative Sky Cubacub decided to start a custom-made, queer crip clothing brand called Rebirth Garments offering a range of bindings and tucking undies that can be snapped on and off through the sides or hook and eyes that are sold on a sliding scale basis (meaning people pay what they can) and offered free of charge for those who can’t afford to pay. Measurements can be done remotely and garments are made from stretchy and flowy materials. The garments aren’t necessarily sexualized unless the wearer chooses to see it that way, which in and of itself is radical since disabled bodies have long been seen as undesirable and un-sexy. Their fashion shows have helped bring the conversation into a larger world, showcasing bodies of all types wearing bright and colorful accessible clothing. “We all have bodies and should be able to wear whatever we want,” they say.

Cubacub, who is considered a leader in the movement, started their brand by doing research and interviewing people about what they wanted, writing a manifesto exploring the idea of radical visibility for the queer crip community (as they’ve built their brand they’ve continued to interview models and ask them about how clothing could be more accessible to their body). In it they wrote, “I am using Radical Visibility as a call to action to dress in order to not be ignored, to reject ‘passing’ and assimilation.”

In their mind, radical visibility is a dress reform movement focused on taking up visual and physical space, and making sure that queer disabled folks are not being ignored. To them, this means designing clothes using bright colors and patterns that clash so people cannot ignore them. “It’s the refusal to be made invisible.”

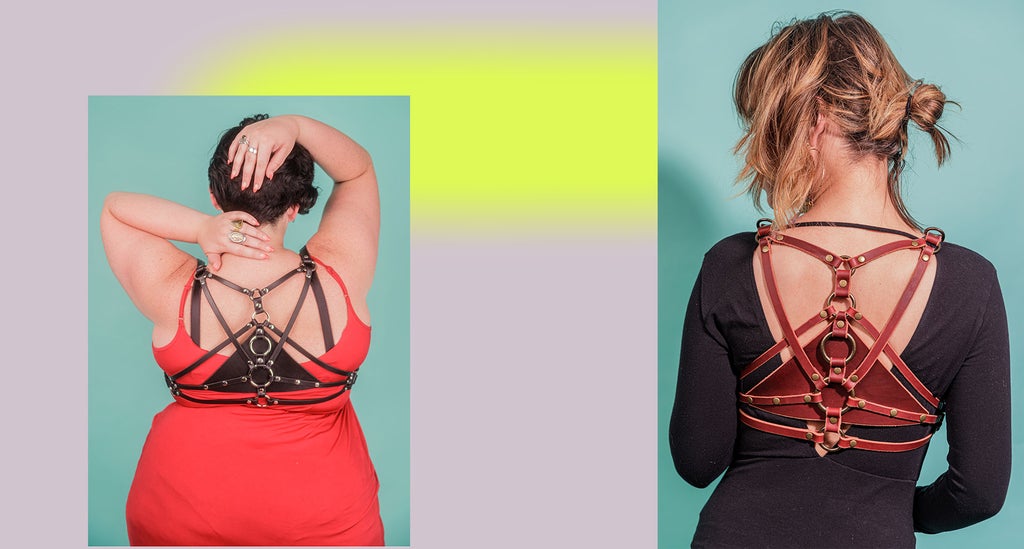

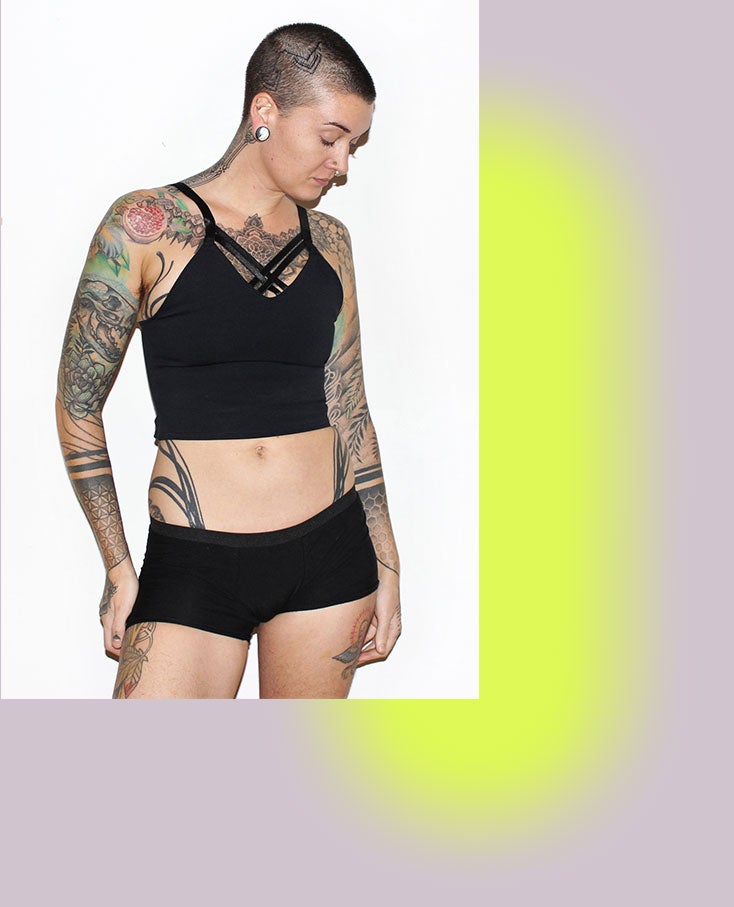

It wasn’t until Emma Alamo met designer Cubacub three years ago, about a year into starting her own fashion line, that she first heard the term. “It immediately gave a name and a movement to a set of ideas and feelings that I’d been struggling to verbalize,” she explains. Alamo was a woodworker until her upper respiratory system stopped working. It took her four years to get her chronic illness to a place where she could figure out a new medium and career. She now designs handmade leather harnesses for every body.

“My own illness made me way more aware of and sympathetic to others with chronic illnesses and disabilities,” she tells Refinery29. “I loved the idea of really owning one’s disability, of not trying to hide it. I saw a need for that mindset in the fashion world.” For example, most medical accessories are beige, which fits the prevailing ideology that medical devices should be strictly functional and concealable. “It’s depersonalizing, and adds to the idea that disability is something to be ashamed of. I want to see this idea turned on its head.”

The Chicago-based creative also sees queer crip as an intersection of the fat acceptance movement. Taking in a rigid, harmful image of beauty while growing up — Alamo had an eating disorder — she says that bigger-bodied people were told to hide their bodies rather than celebrate them and that it’s only recently that these notions have been dismantled. “[Queer crip] fashion emphasizes an individual person’s differences rather than tries to conceal them,” says Alamo. According to her, it is fashion that enables the wearer to celebrate what society so often encourages them to apologize for.

Queer crip fashion isn’t meant to help the wearer blend in. Rather, it offers an alternative: it encourages the wearer to stand out, proudly. This includes modified design elements which are accentuated through bold styles, says Rae Hill, the Montreal-based designer of Origami Customs. The customized and handmade line of swimwear, lingerie, and more is meant for folks of any size, shape, age, ability, and gender expression with each item individually patterned for a perfect fit. “I used to only see accessible fashion which was made to blend in,” Hill explains. “Any fasteners were always hidden, and the styles were subdued and boring.”

Hill initially started their brand creating customized garments for people across the gender spectrum who couldn’t find products in mainstream stores that were gender-affirming and available at any size. Over the years, they realized there was a lot of overlap between trans/gender diverse folks and the queer crip community. “I had always offered customizations, which often included one-to-one navigation of disabled bodies, but a few years ago I started creating specific products for folks with different access or sensory needs.” Now they’ve made shifts for ease of access in almost every product they carry, opting for soft ties in the swimwear as opposed to hard hooks that fasten behind the back and can be hard to reach, for example.

Comfort isn’t just physical: It’s about bodily and emotional empowerment, too. “For me, [queer crip]means clothing that is accommodating to my disabilities while feeling like myself in it. Being comfortable in a disability context and in a queer context,” says Segarra. According to them, “Queer crip fashion is empowerment, it’s a glorious cape that catches air in a twirl; it gives me the opportunity to turn myself into art, to authentically represent myself with my presentation, and be proud of all that I am.”

There is also not one way to dress. “Queer crip can’t be reduced to one specific style, because it is first and foremost about its purpose,” says St. Battie. Queer crip fashion is thus a vehicle for self-expression and experimentation.

Something queer crip fashion grasps that a lot of mainstream fashion misses is that dressing a person involves dressing the whole person, offers model Pansy St. Battie. In this way, designing for diversity is acknowledging the humanity of this community while normalizing the idea that they deserve to be comfortable and experience joy and beauty, says Green Langdell. “Queer crip fashion is about the comprehensive wellbeing of marginalized people.

“Having clothes that fit our bodies and identities is an immensely powerful experience for people who have not been able to find that in our whole lives,” says Green Langdell. It’s also about feeling part of a community — one that is safe and supportive, where people can celebrate their diverse identities free from marginalization.

For example, along with his brand, Green Langdell created Becoming, a transgender health and wellness community based in accessibility, sustainability, education, and collaboration. This includes “trans talk” video series, unscripted conversations among the trans community about gender, colonialism, disability, and a free, online supporting trans students workshop for professors. “Fashion can be powerfully validating, and gender affirming wear can uplift people’s physical and mental health.”

“Queer crip is something that allows us to connect with our community and ourselves,” says St. Battie. “It’s something that takes away the limits of fashion in a world where so, so many things are restricted for people like us.”

HOW TO MAKE THE FASHION INDUSTRY MORE ACCESSIBLE

“This movement has accomplished a lot in terms of uniting queer crip community, giving voice to our stories, naming an intersectional identity we all experience, and creating garments that allow us to express ourselves,” says St. Battie. “What needs to happen the most is queer crip fashion becoming easier to find and more financially accessible.” This, they say, is hard to do while still making sure the designers and creators involved are being adequately compensated.

People outside of the community could make a real difference by sharing queer crip creators and designers and donating to projects that give queer crip clothing and accessories to those who can’t afford them. Fashion brands and companies can play an even bigger role by providing queer crip designers with economic support. This means investing in them, hiring them, and making queer, disabled models highly visible across marketing and social media platforms. “The fact that there are now clothes that are available to purchase that are designed for people with disabilities, that are designed for trans bodies, is revolutionary,” says Green Langdell. “But the options are still so limited that not every queer crip person can find clothes that suit them.”

Designers and brands should be asking if there is anything more they can be doing to make their clothing more accessible rather than creating separate collections. Due to issues such as slave labor and working conditions for garment workers, which isn’t in line with the idea of radical visibility, Cubacub says that mainstream brands are not able to make queer crip fashion in the politicized sense but they still could make gender affirming and adaptive garments.

To avoid tokenization, companies must put time and energy into determining what the community’s needs are, and how to properly address them. This can be done through fashion by hiring queer crip designers, even if the clothes are for more than just the queer crip community. “Queer crip designers are used to working with people to determine exactly what they want and need in a garment, and this skill can be used to make your clothes appealing to a wider audience,” says Green Langdell.

“Accessibility is innovative not just for disabled people but for everyone,” says Segarra. “Mainstream and designer fashion can learn how to make fashion for everyone, not just an elite few, and they’ll be thankful for it. Disabled innovation is groundbreaking.”

Voices of Disability is edited by Kelly Dawson, a disability advocate who was born with cerebral palsy. She has spoken about her disability on the popular podcast Call Your Girlfriend, and written on the subject for Vox, AFAR, Gay Mag, and more. Find her work at kellymdawson.com.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?