A years-long observation program of the planet Jupiter has revealed some of the most detailed images ever captured of the gas giant, exposing the truly bizarre nature of its ultraviolent, planet-wide storms.

Vast swathes of the planet are consumed by ferocious storms the likes of which we have never seen here on Earth; indeed, Jupiter’s famous and permanent ‘Red Spot’ storm is larger than the Earth itself.

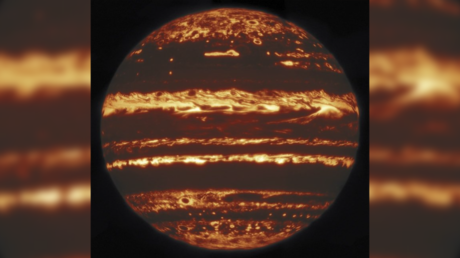

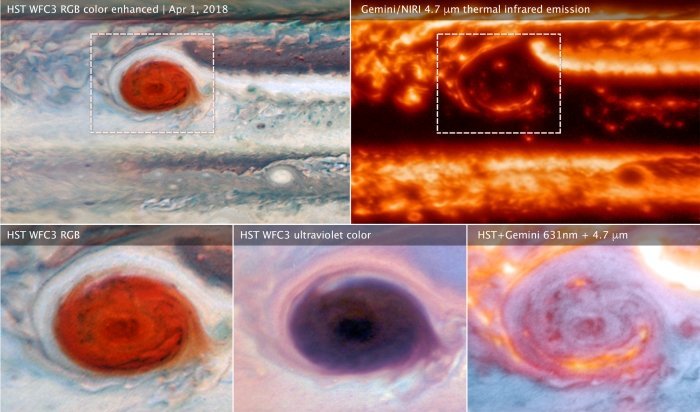

Researchers using the powerful Gemini Observatory and Hubble Space Telescope managed to capture thermal radiation glowing through the planet’s thick clouds, and then to compare and contrast them with optical images taken hours later.

The storm bands that encircle the entire gas giant reach far higher than our own atmosphere, and penetrating the thick smog has proven extremely difficult for even our most advanced instruments, whether space based or located back here on Earth. The combined near-infrared and optical images now finally allow scientists to piece together what’s really going on.

“It’s kind of like a jack-o-lantern,” explained astronomer Michael Wong of the University of California, Berkeley. “You see bright infrared light coming from cloud-free areas, but where there are clouds, it’s really dark in the infrared.”

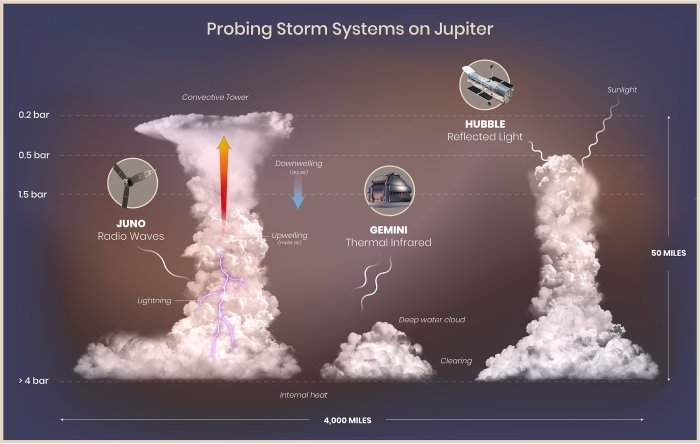

The team then combined their analysis with data from NASA’s Jupiter orbiter Juno, which has been detecting atmospheric radio signals, called sferics and whistlers, from powerful lightning strikes on the gas giant’s surface since it arrived in orbit in 2016.

Since then, most of the observed lightning strikes have taken place at the planet’s poles, whereas on Earth, the majority hit around the equator. Jupiter’s concentration of polar lightning is likely due to the relative size of the two planets, their atmospheric composition and their respective distance from the sun.

As it turns out, these lightning strikes on Jupiter are concentrated in gargantuan tornadoes of moist air over deep clouds of both frozen and liquid water, which researchers believe may act as a kind of energy release valve for the entire planet.

“These cyclonic vortices could be internal energy smokestacks, helping release internal energy through convection,” said UC Berkeley’s Michael Wong.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!