During the Cold War, the CIA heavily promoted one of US’ most popular modern artists, in a covert propaganda campaign designed to tarnish the image of the Soviet Union. Did the subterfuge succeed?

When reflecting upon the Cold War (1947-1989), most people entertain images of missiles, soldiers and tanks taking up positions on either side of the Iron Curtain, not armies of bohemian artists splashing paint against canvases in an outburst of creativity. Yet that is what was happening during this ideological showdown as the US government began weaponizing the world of art in its battle against communism, which was looking increasingly attractive to Westerners disillusioned with the shortcomings of capitalism.

Until the end of World War II, the United States was considered something of a cultural backwater as far as artistic superpowers go. Yes, the capitalist powerhouse might be able to create Disneyland, McDonald’s, and Coca-Cola, the critics sneered, but never anything of lasting cultural value. And in the off chance that something worthy of praise did appear in America’s galleries and art exhibitions, it was most likely the handiwork of the Europeans. After the war, however, the critics toned down their rhetoric as the cultural scales began to tip in America’s favor. Europe lay in ruins, while Paris, once the epicenter of the Western art scene, had become largely devoid of its best artists and writers, many of whom had fled abroad to escape the horrors of Nazi Germany. This momentous migration thrust New York City into the cultural limelight almost overnight.

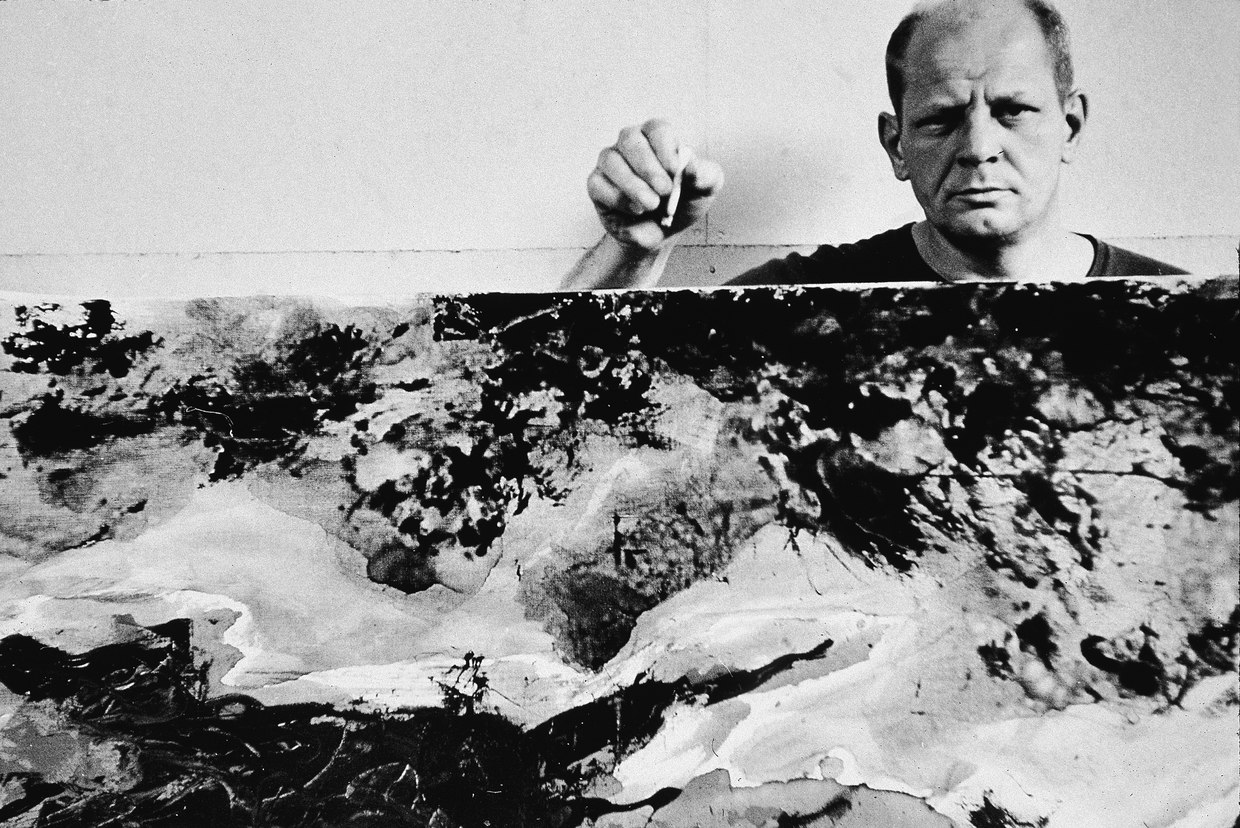

In the late 1940s, below the smog and skyscrapers of the Big Apple, a truly American cultural phenomenon was bursting forth into the world called Abstract Expressionism, an artistic movement that mirrored the frenetic, chaotic energy of the bustling metropolis. Of the many diverse artists who made up this group – Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and Franz Kline, to name just a few – the brooding recluse named Jackson Pollock stands out among his contemporaries not only for his unique style of painting, but for the extraordinary details of his personal life. In his 2008 book, ‘The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America,’ Hugh Wilford described Pollock as “Western born, taciturn, hard-drinking, [Jackson Pollock] was the artist as a cowboy, shooting paint from the hip, an incontrovertibly American hero.”

Born on January 28, 1912 in the Midwestern town of Cody, Wyoming, Pollock made a name for himself with his ‘drip technique’ of pouring and splashing household paint in seemingly haphazard fashion onto typically large canvasses that were positioned on the floor. By comparison, while an abstract work by a Picasso or Braque would contain identifiable details, like a human physique or natural landscape, Pollock’s free-flowing works were a sporadic display of designs and vibrant colors that focused more attention on the painter and the act of painting than the painting itself. “Art was no longer about capturing an experience,” explained Mark Rothko, a contemporary of Pollock. “It was the experience itself.” This radical form of abstraction fiercely divided the critics: while some heaped praise on the spontaneity of the works, others questioned the apparent randomness and lack of forethought that went into the creations.

The art critic Robert Coates derided the work of ‘Jack the Dripper’ as “mere unorganized explosions of random energy, and therefore meaningless.” Reynolds News scoffed at Pollock’s work, stating in a 1959 headline, ‘This is not art – it’s a joke in bad taste.’ Then-President Harry Truman could not resist jumping on the anti-Pollock bandwagon, summing up the popular consensus when he said, “If that’s art, then I’m a Hottentot.” The esteemed art critic of the time, Clement Greenburg, may have had the last word on the matter. In 1943, upon seeing Pollock’s breakthrough work, Mural, a massive 8ftx20ft painting exploding with raw energy, Greenburg concluded, “Jackson was the greatest painter this country has produced.”

Eventually, all this attention in Jackson Pollock and his peers in the Abstract Expressionist movement caught the interest of the US intelligence community, which saw an opportunity through these controversial paintings to challenge the Soviet Union on the propaganda front.

© Tony Vaccaro / Getty Images

CIA, new art connoisseurs on the block

As with every ideological battle between combatants, ideas are paramount. Thus, there is a constant, unseen propaganda war fighting for the hearts and minds of the people. At the peak of the Cold War, the Soviets and Americans were forking over hundreds of millions of dollars/rubles annually to prop up their preferences for the perfect sociopolitical system. And,judging by the palpable paranoia emanating from Washington DC, most conspicuous during the ‘Red Scare’ years under McCarthyism (1950-54), it seemed the Soviet Union was getting a lot of bang for its buck (the fear that pro-communist agitators had infiltrated every nook and cranny in America, from Hollywood to Capitol Hill, was eventually found to carry as much credibility as the bogus charges that ‘Russiagate’ did decades later in the Trump presidency). To tamp down the hysteria, Truman signed an executive order to screen federal employees for possible ties with organizations deemed “totalitarian, fascist, communist, or subversive”, or advocating “to alter the form of Government of the United States by unconstitutional means.”

It was during this time that the CIA received marching orders to ramp up its influence on the cultural front, particularly inside of the art community. At first glance that might seem to be an odd target for an intelligence operation. While it would seem logical for the CIA to infiltrate the mainstream media, for example, as a way of manipulating public opinion during the Cold War (see ‘Operation Mockingbird’), it is less clear what may be gained by intrusion in the New York City art scene. After all, many Western artists and writers of the time, Pollock included, had rather strong communist sympathies and would not have agreed to cooperate with the US government, not to mention spooks. But regardless of their political affiliations, artists by their very nature are notoriously rebellious and independent, therefore the very idea of working on behalf of some political agenda would have seemed appalling to many of them. In other words, CIA agents and bohemian artists make for very strange bedfellows.

So, what was it that attracted the US intelligence community to this radical new artistic movement to begin with? How could canvasses smeared with indecipherable blotches of paint, that few experts could even pretend to understand, provide ammunition in the propaganda war? In the view of the CIA, Abstract Expressionism could be used to promote the idea of personal liberty and free expression over the more rigid and conformist style popular in the Soviet Union known as Socialist Realism; Soviet art was representational and realistic and could only portray life under communism in a glowing light.

Donald Jameson, a retired CIA case officer, was the first to break the silence on the Agency’s covert operation.

“I think that what we did really was to recognize the difference,” Jameson said in a 1995 interview with The Independent. “It was recognized that Abstract Expressionism was the kind of art that made Socialist Realism look even more stylized and more rigid and confined than it was. And that relationship was exploited in some of the exhibitions.”

© TIMOTHY A. CLARY / AFP

Operation ‘Long Leash’

Now American spy craft was confronted with the problem of how to exert its dark influence over the art community and their fledgling movement without drawing undue attention to their machinations. How to make Abstract Expressionism seem to be an independent, grassroots phenomenon when in fact it was not. Incidentally, here we can already see a glaring contradiction in the US government’s plans, which aimed to promote the ‘freedom and individualism’ thought to be inherent in American modern art, while at the same time infiltrating and steering the community for its own political purposes. Such a strategy is the very antithesis to the idea of ‘freedom’ that the Agency was aiming to promote. But more on that later.

In 1950, the CIA kicked off an operation dubbed ‘Long Leash’ that allowed it to become ‘patrons of the arts’ from behind the scenes. To this end, the Agency helped found a front organization with a Soviet-sounding name called the Congress for Cultural Freedom. This group was responsible for secretly channeling funds into the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which, surprisingly, had numerous connections to the intelligence community in its ranks. William Paley, for example, one of the founding fathers of the CIA, was a board member of the museum’s International Program. John Hay Whitney, who had served in the Office of Strategic Service, the wartime predecessor to the Agency, worked as MoMA chairman. Tom Braden, first chief of the CIA’s International Organizations Division, was executive secretary of the museum. Finally, there was the extremely well-connected Nelson Rockefeller, whose own mother had co-founded MoMA. As a former CIA man (in the realm of psychological warfare, no less), and a member of one of the most powerful dynasties in the United States, Rockefeller became an ardent supporter of Abstract Expressionism, which he referred to as “free enterprise painting.”

With such powerful and trusted connections at the very heart of the American art scene and auction houses, the Congress for Cultural Freedom was able to bankroll several international projects, including the Partisan Review, a high-brow journal that was popular among European intellectuals. It also took several exhibitions of Abstract Expressionism on a whirlwind tour, including one entitled ‘The New American Painting’, which visited every major European city to showcase the work of Jackson Pollock, who was always the main attraction.

© Getty Images / Bettmann

Without ever suspecting the role that the US intelligence community played in his spectacular rise to the top of the international art scene, Jackson Pollock went on to enjoy great fame and fortune in his lifetime – until tragedy struck. On August 11, 1956, Pollock, just 44 years old, died in a single-car accident while driving under the influence of alcohol. Ever since the premature death of one of America’s greatest artists, a debate has raged over the influence that the CIA played in Pollock’s life, and what effect, if any, it had in the 70-year Cold War. On both scores, it would be impossible to make any definite conclusions. Undoubtedly, Pollock was a major talent who would have succeeded with or without the secret support of the US intelligence community, but to what degree, again, it is impossible to say.

The same thing could be said for the Cold War showdown. All things considered, it would be hard to argue that the abstract work of Jackson Pollock contributed much to the collapse of the Soviet Union. While his radical work certainly generated heated speculation at New York City cocktail parties, most of the population would not have been able to see a connection between Pollock’s work and the purported ‘superiority’ of the capitalist society that it derived from. In fact, the sentiments of the art critics notwithstanding, many Westerners of the day believed modern art was a sign of moral degeneracy and social decay, more fit for hanging on the wall of a bordello than an art gallery.

Shortly after Pollock’s death, then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower expressed his contempt for the avant-garde that many average people could relate to. Speaking on May Day, 1962, he lamented that “our very art forms [are]so changed that we seem to have forgotten the works of Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci” and then, with an apparent swipe at Pollock and his peers, condemned works of modern art like “a piece of canvas that looks like a broken-down Tin Lizzie, loaded with paint, has been driven over it.”

Eisenhower, himself a part-time artist who dabbled in oil painting, concluded by asking: “What has happened to our concept of beauty and decency and morality?”

That is a question still being asked today by many people when they are confronted with modern art and the cultural scene in general. If the CIA failed to convince even the US president that Abstract Expressionism was the new way forward, then it probably failed to convince millions of other people on both sides of the Iron Curtain as well.