“THIS IS JUST THE START”

T

he Bears’ dressing room looks like any other peewee team’s post-practice: a bustle of 12-year-olds sitting shoulder-to-shoulder, trying to shed sweaters without clocking teammates next to them, shoving playfully, chattering and laughing. Then Andy Metabie, the team’s manager, walks in and raises his right hand to get their attention — because of the chill in All Chiefs Memorial Arena, he hasn’t bothered to take off his fringed deerskin gloves that bear the logo of the New Jersey Devils, his favourite team.

“I’ve got something important, so listen up,” he says.

Metabie understands the limited attention spans of 12-year-olds, so he cuts to the chase. “We’ve been working to get the Bears invited to the Quebec peewee tournament for a few months now,” he says. “We haven’t had a team go there before and only sometimes do they invite a team from our league.”

Looks of puzzlement crease the faces of the players; only a couple have ever heard of the world’s biggest age-group tournament. Bentley Bobbish had his sights set on it for a few years when his family was living in Gatineau, but the 12-year-old in thick-rimmed prescription sports glasses thought any chance to play there had disappeared when he signed on with the Bears. Zane Washipabano has heard his father Charly tell stories about playing in the tournament back in ’96.

“There are 100 teams from all over the world,” Metabie says. “A lot of NHL players played there when they were 11, 12 years old. Some of the games are in great big arenas. We’ve been waiting since the summer to get word from the people in Quebec City who run the tournament. But we heard back that we’re invited.”

The room’s silent, as if the players are waiting for permission. Metabie makes the point clearer: “The Cree Nation Bears are going to Quebec City,” he says.

Cheers break out, a chorus of woos. Metabie takes some questions. Yes, we’ll be going down by bus. If parents are coming, we’ll figure out where they can find hotels. Yes, we’ll be playing in the big arena. No, I don’t know who’ll we be playing or exactly where we’ll be playing them, but they’re coming from all over — we’ve got a couple of teams from France and even one from Italy in our group.

“You’re going to be representing the Cree Nation,” the manager says, finally. “This team has never been to the tournament before, so we want to be really ready when we get there. You got to work hard. When you go home at Christmas, get out there and work out so that you’re ready when you come back in January.”

Even if it were that simple, the road to the Quebec tournament would be a long one for this team to travel. But neither Metabie nor the Bears could know the challenges they would face in the pursuit of their goal — or how often reaching it would seem impossible.

T

his December Thursday night it’s minus-37, cold even by the standards locals are accustomed to in Waswanipi, Que., a community of 1,800 eight hours north of Ottawa on the way to James Bay. As the Bears lug their hockey bags and sticks out of All Chiefs Memorial Arena, they seem inured to the cold — many hatless, many gloveless — and in no great rush to go home. Andy Metabie has his SUV parked and running, and his son Ethan throws his stuff in the back, likewise Washipabano and Zacchaeus Blueboy, first-year peewee players who are living at the Metabies’ home. A couple of other Bears are picked up by their parents in the parking lot, but the rest get rides to their billets’. It’s a reminder that this isn’t a hometown team per se — only four players from Waswanipi skate for the Cree Nation Bears.

By the time you get to peewee, most teams are pretty homogenous — some have kids who started out together in tyke, who have skated in practices and games for four, five and even six years. A few players parachute in at different points along the way, but everybody knows everybody. This stands in sharp contrast to the Bears’ dynamic. Their players met for the first time back in the fall at the tryouts. Other than the four locals, the roster is made up of kids from communities spread across the Cree lands, the Eeyou Istchee, an area of over 400,000 square kilometres. Consider Blueboy, a defenceman from Waskaganish on the coast of James Bay. ”My father drove four hours to get here and the whole time we talked about hockey and what it would mean to make this team and how I had to do my best,” Blueboy says. “I was nervous. I didn’t know anybody and really I hadn’t had a chance to skate since the last winter and hadn’t played in a game since I was a little kid.”

Though 25 First Nations’ territories and reserves encompass vast swaths of the province, the James Bay Minor Hockey League is the only all-Indigenous program fully federated under the auspices of Hockey Quebec. Drawn from the JBMHL, the Cree Nation Bears’ midget, bantam and peewee BB squads are the only all-Indigenous select teams. If Cree parents want their peewee-aged kids to play organized hockey while attending a grade school or high school that offers classes in their first language, respects Cree traditions and enriches their sense of their people’s culture, then the Bears program in Waswanipi is the only option.

Twenty-one kids tried out for 16 spots on the under-13 team’s roster, which made for long, heartbreaking rides home for the few kids who didn’t fare as well as they hoped in the tryouts. “You want to find a way for everyone,” says Metabie, who sits on the Cree Nation of Waswanipi council. “But the fact is, it’s numbers. We can only take so many on the roster and there’s only so many billets for the kids out of the community.”

Distances mean most parents don’t get a chance to see their kids play home games — Blueboy’s parents were fine with the drive for the tryouts in the fall, but in winter conditions pre-empt it, with roads slowed by 18-wheelers hauling lumber, snowploughs crawling along and crossings for snowmobiles and moose. “If I get someone to shoot video of a game on an iPhone I can send it back to my mom and dad,” says Bobbish, whose parents are in Chisasibi. “Mostly I just text them to let them know how I’m doing, every day or two.”

The Cree Bears carry a considerable load on top of the separation from family — the travel to Waswanipi is matched every other week during the season by a road trip that can have them in a van for six or eight hours to a pair of games starting Saturday around lunchtime. “If you take all the teams in the league, they’re spread out over a region that’s as big as France,” Metabie says. “Some teams have it worse than we do and so you’ll have teams stay over a night on road trips. Some do flights to game. Other teams might get more ice time than we do or have come up from novice and atom [as a group], but no team spends more time together over a season than our teams here. Between the time on the ice, the time at school and then at home and then road games, it’s like their whole world. … They’re around each other 24 hours every day.”

This team may preoccupy them in the present, but kids in minor hockey can’t resist looking ahead beyond any given season to some future plan, some dream. In less-guarded moments, some of the Bears will admit that they’re aiming to play at a higher level, hopefully AAA, even if it means moving south. Bobbish looks like a good bet to be able to make that transition. In a couple of weekend games against a team from Rouyn-Noranda in December, Bobbish had a couple of highlight-reel goals, turning a defenceman inside-out with one dangle, going wide and speeding by another before deking the goaltender. He looks like a AAA player and in fact was one — he spent his atom and minor atom years in Gatineau. When his family moved back to Chisasibi a year ago, he tried out for the Bears. “I still text the kids that were on my team in Gatineau,” he says. “I liked it there. It was really good hockey. I want to do something with the game — play junior, play pro. And I know the best chance is AAA. I’ll get seen in Montreal or someplace like that.”

Bobbish says that he liked his time away from the arena in Gatineau and expects that Montreal would be even better, but that wasn’t the experience of Ethan Metabie, the son of the Bears’ manager. A soft-spoken kid, Ethan is one of the smallest of the Bears and certainly the slightest — he’s also 100-per cent gristle, grit and effort. He’s strides ahead of the entire team in line skates at the end of practice and he almost laps the field in dryland sprint training on off-days. He keeps his head on a swivel in games — he’s small enough to sometimes duck under traffic in front of the net. He’s a zero-maintenance player in practice, skating out every line rush, sticking to each drill drawn up like he’s doing it in school for marks. Yet when Ethan went to a weeklong hockey camp last summer in Montreal, he was made to feel like an intruder. “The white kids never talked to me,” he says. “They wouldn’t even look at me. The coaches never called me by name, never talked to me the way they did the white players.”

When he describes the experience, Ethan’s voice, just above a whisper, sounds like he’s trying to suppress his anger while laying out the cause of his resentment. Others tell similar stories and are matter-of-fact about the racism they face. “It’s there all the time,” says Leesha Grant, who felt like an outsider when she went from Chisasibi to a goalie camp in Peterborough, Ont. “A lot of the kids knew each other but they talked to the [non-Indigenous] kids that they met for the first time. Nobody really talked to me even when I tried to start a conversation.”

The five-team Abitibi league that the Cree Nation Bears play in takes them into Rouyn-Noranda and Amos, and even in those communities closest to the Eeyou Istchee, young Indigenous players hear racist taunts from opponents and those in the stands. “I’ve seen it with my son when his team [from another community]has gone to a tournament in the south and he was getting hassled by a couple of players from another team in the lobby of the hotel,” says William Saganish, a former policeman who coaches the Bears. “I went to the coach [of the other team]and we were able to identify the players involved. To the coach’s credit, he made it clear that any stuff like that wouldn’t be tolerated, but that doesn’t fix the damage that’s been done. And maybe my son only says anything because I’m there — how many Cree kids wouldn’t say anything about it to a coach or an adult with the team, not wanting to make trouble? They’d think that talking about it makes it real and makes it worse … that they’re not ending it but making it worse. They just hold it in. I wish all kids would talk about it.”

Officials on the ice have it at their discretion to shut down attacks at the first slur or taunt, but too often miss it or, worse, enable it. “The sad thing is that kids get used to it,” says Tommy Grant, a QMJHL goalie back in the ’80s who has coached Waswanipi teams in all age groups. “We had a midget AA team that faced a lot of it a few years back. We got it bad when we went to Hearst, [Ont.], fans coming up yelling slurs behind the bench. We got some more when we went to Rouyn, but the worst was a tournament we played in Drummondville. The officials went to the other team and told them to cut it out. I told the boys, ‘Don’t let it get to you. Play your game. You’ve heard it all before.’ And we ended up winning the tournament.”

A happy ending, yes, but Grant says that no one should cast the incidents as his players turning harassment and abuse into motivation. That would be giving too much credit to those who heckled and taunted the Waswanipi team. “It didn’t make the boys play harder,” he says. “Getting mad about it could go wrong. You can’t pretend it’s not out there either — it’s ugly and I saw the pain in their faces. I put it out there to all of them, ‘I know you hear it. I hear it, too. We all hear it.’ Just saying that it’s out there makes it not so tense. It’s something we all share, so let’s get on with the rest of it.”

Though their sons have experienced everything from chilliness to racist abuse, Metabie and Saganish still believe the trip to the Quebec tournament will serve as a fitting reward for the work the kids put in — feeling that joy of playing on a bigger stage than they ever imagined. They also see it as a particularly enriching experience for the U13 players. While the older teams in the Bears program have a chance to see a greater variety of opponents, the peewees play only four other teams across the regular season and playoffs. But after the prospect of the trip starts to sink in with the players, Metabie, Saganish and the rest will be hit with a few more surprises — and not all of them welcome.

F

ive days after the Quebec tournament’s officials approved their entry, Metabie and Saganish round up the Bears for what the players are told is a team meeting. The parking lot is crowded when they get to the arena, which maybe gives away that something bigger is in the works. Once inside, they’re led not to the dressing room but the stands — the Bears’ bantam and midget teams are already there in the seats.

A red carpet is rolled out to centre ice and Metabie and Saganish set up a screen close enough to the boards for those in the seats to get a good look at it. Metabie tells everyone that there’s a video that he wants them see. It starts with glitches and shakes — clearly not a professional production but rather something shot on a phone’s front-facing camera. As it turns out, it’s a phone that belongs to Carey Price. The Montreal goaltender is sitting in front of his stall in the Canadiens’ dressing room. He’s in street clothes, still months away from putting on equipment again. Price says that he has a message for the Cree Nation Bears and it’s easy to tell he’s not working from a script. “I understand what it’s like to travel thousands of kilometres to play the game that you love,” he says.

Everyone in attendance knows the truth of that statement. The story of Price’s career — the Vezina Trophy, the Olympic gold in Sochi and the unlikely run to the Cup final last spring — is well-established lore for hockey fans in Quebec, and his personal history is a source of pride and inspiration to the Bears. They’ve heard the stories of the long road that he took to the NHL and the Olympics — how his father, a bush pilot, had to fly Price to practices and games in youth hockey because their home in Anahim Lake in central British Columbia was so remote. The adults in the stands likely know that his mother is in fact chief of Ulkatcho First Nation.

“I want you guys to play with respect,” he says. “I want you to play hard. I want you guys to be warriors. I want you to respect your opponents, respect the officials — and most of all, respect yourselves.”

Price’s speech to the team is followed by other recorded messages, one from former NHLer Jonathan Cheechoo, who grew up playing hockey in the Moose Cree community in Moose Factory, Ont.; another from current NHLer P.K. Subban.

And then comes the payoff: Metabie appears with a couple of sweaters and tells the players and the rest of the crowd that they’re prototypes of the ones the Bears will wear in Quebec. The sweaters, he says, come with a story and he proceeds to tell it — how Adidas heard about the team’s application for entry into the Quebec tournament; how the company’s design staff worked with Landen Spencer, a teenage Cree artist in Mistissini, to come up with new logos and colour scheme. And then the sweaters are held up and appear on the screen, home and away: The orange trim evokes Every Child Matters, the initiative to honour the generations of youth coldly taken from their parents and forced into the residential-school system; the image of ribbons on the shoulders is a tribute to missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. On the black home sweaters, the logo’s ‘C’ is framed with claws. On the road whites, ‘Cree’ is spelled out, descending diagonally across the front in the classic Rangers’ style. Above the numbers on both, players’ names are spelled out in Cree syllabics. Adults nod their approval and some start to clap, but most of the peewees silently look on, as if they know this is significant but might struggle to come up with the words to explain why.

Finally, Juness Bearskin says what’s on his mind and maybe on the minds of some of his teammates: “Do we get to keep them?”

T

wo days later the peewee players wear those new sweaters for the first time. Those parents who live within driving distance of Rouyn-Noranda — that is, six or eight hours each way — come in for the Bears’ games against the two teams based in the town the weekend before Christmas.

On Saturday, the Bears lose 5-4 to the Capitales at the Arena Jacques Laperriere. But on Sunday at the Arena Dave Keon, they run out to a 3-0 lead against the Citadelles on goals by Lazarus Kakabat, Bobbish and Washipabano, his team-leading 10th of the season. In the third period, the Citadelles rally with a pair of goals but Bears goalie Myles Cooper, playing through a knee sprained the weekend before, holds off a flurry of shots to send the players off on their holiday break feeling good about their game. “The two games set us up in a good way to prepare for the Quebec tournament,” Andy Metabie says.

While some of their teammates go home with their parents Sunday afternoon, the few Bears from more remote communities ride in Metabie’s and Saganish’s SUVs to the Rouyn-Noranda airport and boarded Air Creebec flights. But before anyone can settle in for the holidays comes the news that, with the Omicron variant of COVID surging, the Cree Nation is going into lockdown. School in Waswanipi is suspended, with classes commencing online in mid-January. Travel into and out of town is limited to essential services; volunteers will drive an hour and a half to Chibougamau on weekends to pick up supplies for the community. Bears players are told they’ll be staying in their home communities for the foreseeable future — though the future is not foreseeable at all. Not just the hockey season but the entire lives of the Cree Bears are put on hold. As is the hope of their season: their appearance in the Tournoi de Hockey Peewee.

In January, officials in Quebec announce a postponement. Until it was called off in 2021, the tournament had always coincided with the Quebec Winter Carnival in February. Most minor-hockey programs run through late March with just a few AAA teams, the powerhouses, playing a handful of games in early April. Now, freshly drawn plans call for a spring event, the tournament tentatively scheduled for the first two weeks of May.

Where there’d been chatter in the dressing room and on the ice, now there’s only chatter between the Bears online. They don’t discuss practicing or working out — arenas in their communities are closed and, likewise, outdoor pads where they might jump into a game of shinny. Housebound for the most part, there’s nothing to talk about except for there being nothing to talk about. One text exchange between teammates who haven’t seen each other in over a month seems to capture the mood:

“Yo”

“Yo”

“It’s been a while, huh.”

“Yeah.”

“r u bored”

“yeah ofc”

“me too”

“it’s so boring”

Says one adult who works with the team and knows the players: “You can tell they’re hurting. They really need to something positive. Kids this age do. Kids who’ve already been through what they have so far with COVID … who were so invested in playing the game, they need a chance to play again. It can’t end this way.”

I

n early March, the province of Quebec loosens restrictions and officials with Hockey Abitibi-Temiscamingue discuss how to make up for lost time — for two full months of the peewee teams’ seasons. They settle on a one-weekend tournament in Amos featuring all five teams, games running all day Saturday and then playoffs on Sunday. The reboot is fine for the other four teams, which draw on players from their own community, but much less so for the Bears. Only four of the peewee from other communities return to Waswanipi to finish their school years — the rest have enrolled in schools closer to home. Those in Waswanipi, eight players, can practice together but the rest will join the team only for the weekend in Amos. Says Leesha Grant, one of the players who has returned to Waswanipi: “I think if we had the choice, everyone would have come back to play, but we know [parents]had to make decisions. It’s easier for me than a lot of them because I can stay with my aunt and uncle here. No one knew if we’d ever play another game.”

Predictably, the Bears struggle in Amos against teams that have been back on the ice practicing for a couple of weeks. The Bears win just one of their four games on Saturday and don’t advance to the Sunday playoffs.

In the face of all the challenges, hardships and losses, Metabie, who misses the weekend along with Ethan after COVID hits their household, remains upbeat: “Quebec was going to be a highlight of our season if we had got there in February but they’d still have a lot of games to play after it,” he says. “Now it’s something that we have to build for. I still think the team hasn’t played its best game yet.”

A

t points along the way, it looked like the Bears wouldn’t be back on the ice until next winter, and by then it would be a new group of kids with a few holdovers. And yet on May 1, they’re in All Chiefs Memorial Arena, standing at the gate, waiting for the Zamboni to finish circling the rink. It’s their first team practice since the second week of December, the day they received their sweaters. They’ll squeeze in four practices over as many days this week. Still, it’s hard to imagine any other team having less time on the ice together before Quebec. Compare the Bears’ year to, say, a U.S. AAA teams whose schedule was little disrupted: According to their website, the Little Caesars AAA team in Detroit went 52-14-5 as of mid-April. For the Bears, this is starting all over again.

With snow on the ground in Waswanipi, it still looks like hockey season. This harsh winter might benefit the Bears: Well into April they were able to skate on flooded backyard rinks — not a great substitute for games and practices with teammates, but better than nothing and, when homebound for long stretches, better than endless hours looking at screens.

This is the first time since tryouts that the Bears and all their families are in Waswanipi together. Cree schools are on break for goose-hunting season, a rite of passage and a high holiday here. Metabie and Saganish were uncertain whether families would be willing to give up their trips together into the bush. And a few plan to fit excursions around practice. Most, though, stay on and watch and talk about their plans for the trip south.

When the day comes, the players climb into the backseats of their parents’ cars, some squished in with siblings and other relatives, for the seven-hour drive south. As kilometres of road fly by, snow gives way to thaw and then bloom. When they arrive in the provincial capital, temperatures are hitting the mid-20s.

It’s late Saturday night when the team checks into a Best Western, and the next morning they don’t have time to see the sights. The schedule calls for them to be at a rink early Sunday afternoon. It’s ostensibly a practice, but the media is in attendance and most of the players’ time at the arena will be taken up by a video shoot with a crew from Adidas. The apparel company shoots portraits of each player skating in a dark arena, lit only by some studio lights and shrouded with dry ice. It’s closer to music video than game action. Then the players are taken aside and mic’d for interviews — an experience that would have to land somewhere between distracting and downright overwhelming for even the worldliest 12-year-old.

Later, at the arena, the Bears get an eyeful of a game between the Whitby Wildcats, and a team from Slovakia. The BB level is effectively the entry level for the tournament with intermediate categories building up to AAA, the tournament’s elite. Without knowing anything about the teams going in, it’s clear these kids from the suburbs outside Toronto and the Slovaks are advanced 12-year-olds. The Whitby powerplay is as organized and structured as a major junior team’s — middle-school kids throwing the puck around almost too fast to pick up at ice level. And while Bears defenceman Connor Napash is a pre-adolescent giant at over six feet, the Slovaks have three kids his size or bigger — they look like they’re ready to report to the NHL combine. One Slovak winger with a Jagr-inspired mullet blocking out his name takes a breakout pass almost a stick length behind, neatly deflecting it up between his skates and wheeling by a Whitby defenceman without missing a stride. The Bears are impressed but maybe not as blown away as the adults with them. They know their team would be in tough against the AAA teams, but this is the level they want to achieve, where they want the program to get to someday. “The objective for us would be to become a AAA program that the very best Cree kids can play for,” Metabie says. “That we can develop that talent and compete. And that we’d come back to the Quebec tournament each year qualifying for it, representing our region and the Cree Nation. We’ve got a lot of work do, but just being here is a start.”

M

onday, game day. The Bears walk through the players’ entrance into the Videotron Centre, home of the QMJHL Remparts and, really, an NHL arena in search of a franchise. Roughly half the players on the Bears’ roster have been to a NHL game, in Montreal or Ottawa, but it’s one thing to look down from the stands and another to take in the view under the lights at ice level. “It looks even bigger down here looking up,” says Bobbish. The arena seems even vaster because it’s about 95-per cent vacant, with just a few hundred spectators in attendance — a couple of grade schools have given their students a break from class and brought them out to watch the action as a field trip.

In the dressing room, the players don their new unis. Saganish goes through the lines. He has no scouting report to give the Bears on their opponents, the Nord-Est Barons, a crosstown team in the Chaudière-Appalaches league — in the Abitibi league, they’d know some about a few of the better players. This game is the season in microcosm: things having to be figured out on the fly.

Ten minutes before the scheduled puck drop, Mandy Gull-Masty, Grand Chief of the Quebec Cree, walks into the room. Wearing a new Cree Bears sweater, No. 22, Gull-Masty begins with a few words in English. “I wanted to have a chance to see you play before I go back for the goose hunt,” she says. The Grand Chief then switches to Cree, the Bears’ first language at home. She tells them to be proud to have come this far to represent First Nations people. At the end of her speech, the adults in the room politely applaud, while the more outgoing players bang their sticks.

“Sports means so much in our communities, especially to young people, and I think there has been more for them than there was 10 or 20 years ago,” Gull-Masty says at a reception with tournament officials afterwards. “Sports gives lives structure and joy and hope. But this team, they’ve lost so much this year, the last two years really. When I look around the room, I see an eagerness in their faces. They’re ready to start again … to pick up where they left off.”

A few minutes later, the Bears look less eager than anxious. They come out for warmups and skate laps of their end. They fire shots at the goalies who’ll split time in the game, Grant and the starter Cooper, as arena staff roll a red carpet out to the centre of the ice. The Bears and the Barons line up along the blue line. Tournament officials make speeches to welcome the team before passing the mic to Grand Chief Gull-Masty. She stands between the captains of the teams for a ceremonial puck drop. The kids in the crowd cheer and the players bang their sticks on the ice. It all takes 10 minutes or so, but still, this on-again-off-again is of a piece with the Bears’ season, which has really been on-and-off-and-hope-it’s-on-and-then-maybe-not-and-then-how-can-they-pull-this-off-and-finally-pack-your-bags-it’s-on-and-yeah-it’s-definitely-on. The players’ heads swivel during the proceedings, taking in the scene, the blindingly bright lights. Standing through ceremonies like this discombobulates veteran pros, so how might it unnerve 12-year-olds moments before the biggest game of their young lives?

All the build-up seems like tempting fate, and through the first few shifts, the game feels like a guaranteed anti-climax. The Bears fall behind early, 1-0 after 90 seconds, 2-0 just six minutes in. It’s not just that they’re being outplayed and beaten to loose pucks, not just that the Nord-Est end looks like it’s just been flooded. No, the energy isn’t there and the body language is telling a dispiriting story. After a couple of big collisions, a couple of Bears players stay down on the ice until play is stopped and they’re helped off the ice.

In the stands, parents are doing their best not to betray any anxiety, as if they’re worried about seeming worried. And Metabie and others who work with the team know better than some of the parents just how unpromising it looks: The Bears’ tendency during the season was to start well and then tire out.

But then, two minutes later, completely against the run of play, Washipabano takes the puck from deep in his own end and skates 150 feet, through a couple of Barons forwards and around a blueliner to make it 2-1. The game turns completely. The Bears find their legs and with every shift their confidence grows. Two shifts after Washipabano’s goal, Juness Bearskin finds Napash with a pass and the big defenceman roofs his heavy shot to tie the game. The mood lifts in the section of Bears parents and family in the crowd — their kids aren’t just in the tournament, they’re in this game.

In the second period, the Barons regain the lead, but again it’s Washipabano scoring, this time with a backhand, to make it 3-3. The Bears take the lead on another big shot from Napash coming in from the point midway through the third. But the Barons get the equalizer on the very next shift, Grant overcommitting to her glove side, scrambling back a tick too late to shut down a shooter on the edge of her crease.

Before the tournament, Saganish sat down with the parents and let them know that, while everyone would get a chance to play and ice time would be spread evenly in a couple of exhibition games later in the week, he intended to shorten the bench if the Bears found themselves in a position to win a tournament game. “We’re not going to Quebec to play,” he told them. “We’re going there to try to win. That’s what the players want: the best chance to win.”

As regulation winds down, Saganish leans on his strongest players, rolling two lines. It seems like Washipabano, Bobbish and Napash go to the bench only for pitstops before they’re back out there. The teams exchange chances in the last few shifts — Grant makes one sprawling save in traffic that’s a game-saver — but no one in the rink seems surprised when the game goes to the five-minute overtime.

With each side down to three skaters, it seems like there’s nothing but wide-open space on the ice, acres of it. Both Washipabano and Bobbish have five-star chances in the first minute but their shots miss the net by inches. Then, when Nord-Est gets possession in the Cree Nation end, the two are stuck out there — they’re on the ice for the first two minutes, exhausted, barely able to make it to the bench.

Still knotted through five minutes, the game goes to a shootout.

Washipabano leads off, skating in with speed and wiring a wrist shot that the Nord-Est goalie, Samuel Caron, stops with a great glove save. The Barons’ first shooter tries to deke Grant but she’s all over it. X-X.

In the second round, Blueboy goes glove-side like Washipabano, but he beats Caron. Grant gets deked out by the Barons’ shooter moments later to keep it all square. X-X-√-√.

Third round: Bobbish beats Caron with a wrist shot on the blocker side and exults. Finally, with the game on the line, the Nord-Est shooter comes in on Grant, who waits and waits and waits without biting, and then kicks out a pad to deny a deke.

Cree Nation Bears 5, Nord-Est Barons 4 in a shootout. The grade-schoolers in attendance let out a high-pitched cheer and the tournament theme music comes in over the P.A. while the Bears empty the bench and mob Grant.

C

harly Washipabano and his mother Dolores, Zane’s grandmother, watch the Bears skate down the handshake line.

“It’s great, not like my Quebec tournament,” he says. “We were living in Montreal back then —my mom was working as a nurse there and I was the only Native kid on the team. It was a good time but this is something really special, to be part of a Cree team.”

It’s mid-May, when minor-hockey seasons are usually long over, so it’s hardly a stretch for kids and their parents to look ahead to next fall. Some big decisions lie ahead. For the kids born in 2009 — Bentley Bobbish, Connor Napash and Leesha Grant among them — they’ll be graduating up a level, perhaps to the Cree Nations Bears’ bantam squad in Oujé-Bougoumou, or perhaps in points south, as Bobbish has talked about.

The Washipabanos have already had this conversation. “Zane’s a first-year player, a 2010 — he’s got another year of peewee,” Charly says. “I asked Zane the other day if he wanted to play AAA in Amos. He could go tryout this summer. I made it his choice completely — I’d support whatever he wanted. He’s looking to play at a higher level and go somewhere with his game. It’d be tough in Amos, French only in school there. No English — and no Cree, of course. He told me he wanted to go back to Waswanipi. There was no doubt in his mind. He’ll be able to wear the sweater with his name on his back in Cree for another winter. I’m sure that coming here has played a big part of it — a chance to be a leader. The program is going to grow when we can attract kids who’d play AAA elsewhere or keep young players who might look at that as where they want to go.

“This is just the start.”

They get to keep their sweaters.

In the second round, the Cree Nation Bears came from behind to defeat the Saint-Laurent Spartans 3-2 with Connor Naposh scoring the game-winner in the last minute of regulation. The Bears’ tournament ended with a 5-2 loss to the Aosta Gladiators. Aosta, an Italian team, won their next two games to claim the BB division’s championship.

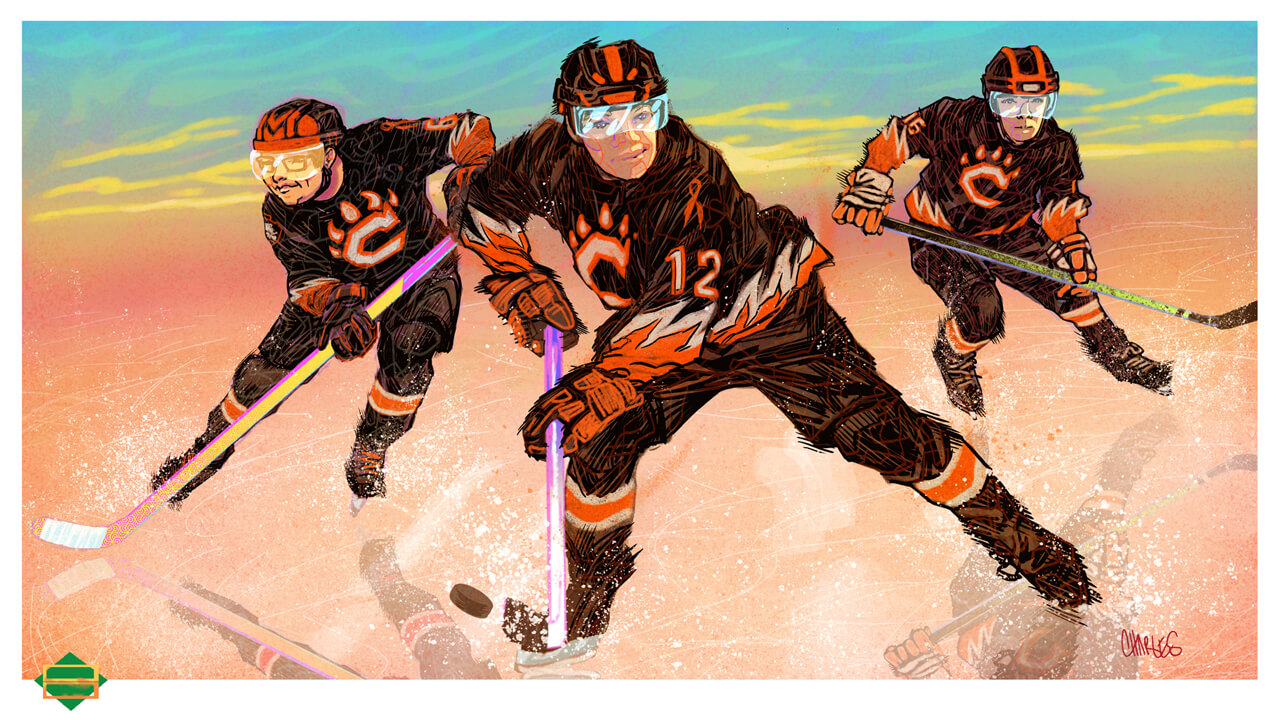

This story features illustrations by Kyle Charles, an Edmonton-based Cree artist whose work has appeared in DC and Marvel publications.

Kyles Charles/Sportsnet (4); Thierry Pateau/Adidas Hockey (3).