In just one day, Croatian Nazi allies killed more than 2,300 Serb civilians in three villages and a mine, without firing a shot

“It was the single biggest slaughter of civilians in their homes in a single day, in such a small rural area – not just in the Second World War, but in the entire history of humanity.”

Those are the words of Lazar Lukajic, a Serb historian, describing the genocidal rampage that took place over some 10 hours of February 7, 1942, less than two miles from where he lived.

The entire world has heard of Lidice, a Czech village that was destroyed by Nazi Germany in reprisal for the resistance’s assassination of the SS occupation governor, Reinhard Heydrich. In June 1942, the Nazis shot all of the village’s adult males and sent its women and children to death camps, before razing Lidice to the ground. A total of 340 villagers were killed. German propaganda proudly trumpeted this atrocity to discourage resistance elsewhere.

Yet few know the names of Drakulic, Sargovac and Motike – the villages where several months prior, it wasn’t Hitler’s Germans but their Croatian allies that massacred over 2,300 people in a single day, using only axes and mining tools.

“Without a single bullet being fired… Every single victim met their murderer face to face, on their own doorstep, before being slaughtered in cold blood,” Dragana Tomasevic, director of the Jasenovac and Holocaust Memorial Foundation (JHMF), told RT.

The villagers were killed solely because they were Orthodox Christian Serbs. In the Independent State of Croatia – a militantly Catholic client state allied with the Rome-Berlin Axis – that was grounds enough to be killed, expelled, or forcibly converted, in a genocidal campaign that served as the opening chapter of the Holocaust.

It was no coincidence that the killers – members of the bodyguard regiment of the Croat Poglavnik (leader) Ante Pavelic – were accompanied by a priest. Fra Tomislav Filipovic, a Franciscan from the nearby monastery of Petricevac, would go on to become known as “Friar Satan.”

Prologue to the Final Solution

February 7, 1942 was less than three weeks after the notorious Wannsee Conference, the gathering of high-ranking Nazis at which they decided that the “final solution of the Jewish question” would be genocide. By that time, however, Hitler’s Croatian allies had already been killing Serbs and Jews for months.

The Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Drzava Hrvatska, NDH) was proclaimed on April 10, 1941 – just four days after Axis forces invaded Yugoslavia. Originally intended as a client of both Germany and fascist Italy, it was under the operational control of the Ustasha (literally “insurrectionists”), a fascist-inspired nationalist movement that defined Croat identity through the prism of militant Roman Catholicism and hatred of “Eastern Schismatics,” i.e. Orthodox Serbs.

More than two million Serbs found themselves under NDH rule in territories of present-day Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and parts of northern Serbia. They were denied their own name, called only “Greek Easterners,” and were immediately placed under the same kind of restrictions that Jews in Germany had been subjected to under the Nuremberg racial laws. The Pavelic regime also outlawed Jews and allowed for the seizure of their property. Pogroms in major cities such as Zagreb and Sarajevo began almost right away.

It was the Serbs that the NDH focused on, however, seeking to kill a third, expel a third, and convert a third – a policy formulation attributed to both Culture Minister Mile Budak and Justice Minister Andrija Artukovic.

“The omission of Croatia from the conventional Holocaust studies is like a book whose first chapter is torn out,” wrote the late Jonathan Steinberg, a professor of modern European history at the University of Pennsylvania and a noted Holocaust scholar. Steinberg also described the NDH targeting of Serbs as the “earliest total genocide to be attempted during World War II.”

The first recorded mass murder of Serbs was recorded in Bjelovar, a city some 50 miles north of Zagreb, on April 27-28, 1941, when about 180 unarmed civilians of all ages were shot. Soon, however, the Ustasha began saving bullets and favoring cold steel – knives, hammers, axes and even improvised implements – to butcher their victims.

Starting in May 1941, the Ustasha used the natural ravines of the Dalmatian hinterlands as pits for thousands of murdered Serbs – sometimes still alive when they were thrown below. Only the intervention of outraged Italians forced them to close the camps such as Jadovno and the Pag salt pits, in August 1941. By then, however, a new series of camps was in the works – the Jasenovac complex, on the Sava River, in the German zone.

Hitler himself had endorsed the persecution of Serbs – whom he blamed for the demise of Germany and Austria in WWI – and urged Pavelic against showing “too much tolerance” at a meeting in June. This meant that reports from General Edmund Glaise von Horstenau, his military envoy to Zagreb who spoke of the “madness” of the Ustasha and warned that their atrocities were fueling the Serb resistance, fell on deaf ears.

‘Like sheep when a wolf attacks’

Massacres of civilians as collective punishment for insurgent activity were routine in occupied and partitioned Yugoslavia. In German-occupied Serbia, the policy of shooting 100 civilian hostages for every Wehrmacht soldier killed and 50 for every one wounded had managed to temporarily discourage the royalist resistance, but the Communists carried on regardless. Several units of Communist Partisans operated on Mt. Kozara, northwest of Banja Luka, in present-day Bosnia but then part of the NDH. Responding to one of their railroad raids, the local Ustasha shot dozens of civilians in the hamlets of Piskavica and Ivanjska on February 5 – and would do so again a week later, killing a total of 520 people.

What happened on February 7, however, was not a reprisal massacre at all. The company of Ustasha, detached from Pavelic’s own bodyguard regiment, came directly from Zagreb with only one mission: kill every Serb they could find.

Dragan Stijakovic was 16. When the Ustasha came to his home in Motike, he hid under the bed. In testimony recorded in 2003, he described how an Ustasha bayoneted his entire family to death, starting with his mother.

“The Ustasha stopped in the doorway briefly and in silence, looked around the room, then went through the door and pushed the bayonet in my mother’s chest, just under the left breast,” he said. “When she fell, the Ustasha took his rifle and plunged the bayonet into her face, stabbing her just under left eye.The rest of my family continued to look on in horror. Completely frozen, paralyzed; rooted to the spot like sheep when a wolf attacks,” Stijakovic added. The Ustasha then “calmly… stepped over my mother and started stabbing one by one, as if stabbing the bales of hay with a pitchfork.”

A telegram sent from Banja Luka to the Ustasha Surveillance Service (Ustaska Nadzorna Sluzba, UNS) in Zagreb on February 11 describes the killings this way: “One company of Ustasha troops, commanded by Oberleutnant Josip Mislov… on February 7 at 04:00 seized Rakovac mine and used pickaxes to kill 37 Greek Schismatic workers. Continued to use pickaxes and axes to kill Greek Schismatic men, women and children in villages of Motike, where around 750 were killed, Drakulic and Sargovac, where around 1,500 were killed. Killing ended around 14:00… Detailed report to follow.”

Neighbors’ betrayal

How did the Ustasha from Zagreb know who to target? Both Serbs and Croats lived in the three villages. The clue is found in the follow-up report, which names some of the local Croats who acted as guides.

From the mine, the Ustasha proceeded to Drakulic, the report says. They were guided by three local men – the miner Ivo Juric, Stipo Golub, and Simun Pletikosa – who pointed out the Serb houses. Everyone was taken outside and killed. The company then moved to Sargovac. On the way back, they slaughtered 70 families in the village of Motike as well. Axes were used for the killing in the villages, in addition to mining picks. The Croat villagers then looted the food, livestock and even furnishings from the Serb homes, but were told to bury the dead. The burials went on for three days.

“Many bodies were buried without limbs, as they had been eaten by pigs and dogs,” the report noted.

A photograph, taken by Ustasha Stipe Kraljevic, shows six of his comrades posing with the severed head of Jovan Blazenovic, a Serb from Drakulic. Four of the six have been identified: Ante Pezic, Meho Ceric, Franjo Likanac and Marko Kolakovic. The extended report also details how the slaughter at Rakovac was carried out: The miners were ambushed when they came to start their shifts, with the Serbs separated, then struck with blunt implements and “finished off” with picks to the head. The same method was used against the third-shift miners who were returning to the surface. The bodies were thrown into the mineshaft.

Both of the reports are contained in the book ‘Friars and Ustasha Slaughter’, published by Lazar Lukajic in 2005. It also contains the testimony of Dragan Stijakovic and 12 other surviving villagers. According to Lukajic, the total number of Serbs killed in the massacre was 2,315, of which 1,363 were from Drakulic, 257 from Sargovac, and 679 from Motike, as well as 16 miners from other villages who were killed at Rakovac.

‘Father Satan’

Tomasevic, who heads the JHMF charity in the UK, is the granddaughter of Dragan Stijakovic’s brother Mladen, who was in a German prisoner-of-war camp at the time of the massacre. She told RT that Friar Filipovic of Petricevac did not just accompany the Ustasha company, but personally took part in the slaughter.

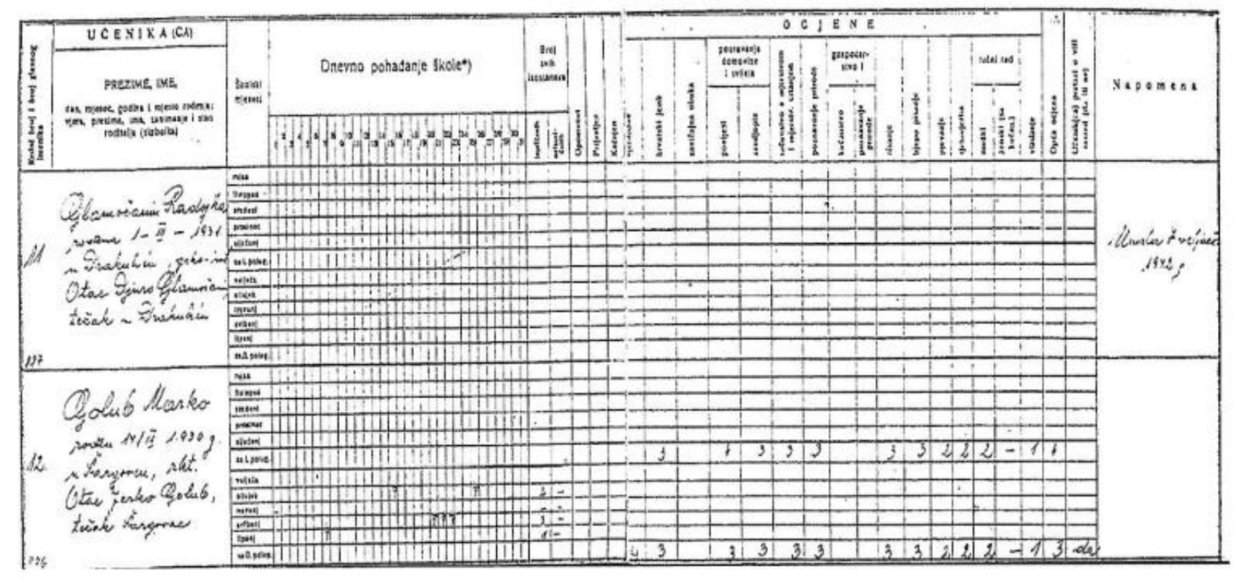

Mimicking Christ and his apostles, the friar took 12 of the Ustasha into the elementary school in Sargovac, where he started butchering the children. Dobrila Martinovic, the schoolteacher who survived the slaughter, later told Lukajic that Filipovic personally murdered the seven-year-old Radojka Glamocanin in front of her, to show the others how to kill. A page from the school log for February 7, 1942 lists 58 Serb children as dying of “natural causes.”

Filipovic also reportedly told the Ustasha that he would absolve them of any sins, and that their killing was “baptizing” the “apostates.” After word of his role in the massacre got out, the abbot of Petricevac defrocked Filipovic, and the German military envoy, General von Horstenau, demanded he be prosecuted. Though the former friar was court-martialed and jailed, his fall from grace did not last long. In March 1943, he caught the attention of Vjekoslav ‘Maks’ Luburic, the Ustasha in charge of Croatia’s death camps. Luburic dubbed the ex-friar a “master of his trade” – i.e. killing Serbs – after which Filipovic took on the second surname, “Majstorovic.”

Luburic had Filipovic-Majstorovic appointed commander of Stara Gradiska, one of the camps in the Jasenovac complex, where Serb inmates were slaughtered with knives, axes, hammers and other blunt instruments. To his victims, he became known as “Fra Sotona” – Friar Satan.

Captured by the Communists after the war, Filipovic-Majstorovic was put on trial for war crimes and hanged in 1946, dressed in a Fransciscan frock. He was never excommunicated by the Catholic Church.

The sin of silence

While some of the butchers of Drakulic, Sargovac and Motike were punished at the end of the war, many more were not. Disclosing the full extent of Croat atrocities against the Serbs would have made it impossible to put Yugoslavia back together after the war. Though the Communists originally intended to break it apart – their infamous 1928 agenda called for its partition along ethnic lines to destroy “greater Serbian bourgeois imperialism” – they were less inclined to do so once they were in power, and had the backing of both the Soviet Union and the Western Allies.

So while the NDH genocide was acknowledged, it was declared that the Serbian royalists were the moral equivalent of the Ustasha and that the Communist Partisans were the only true resistance to Axis occupation. Peoples of Yugoslavia were told to embrace equity, in the form of “brotherhood and unity” – and if that meant living next door to one’s executioners, so be it.

This meant that the survivors had to wait years to recover just the family heirlooms looted by the neighbors implicated in the slaughter of their relatives. The same neighbors found jobs and power in the new government. A discreet monument erected to the victims of the Great Slaughter in the 1960s could not identify them as Serbs, so as not to hurt the Croats’ feelings.

This is also why the Stijakovic brothers and other survivors could not get their testimonies published until the 2000s – long after the propaganda of the 1990s smeared the Serbs as genocidal war criminals and their WWII executioners as innocent victims, in a new “history” written by the Cold War victors.