The ambitions of a Soviet-backed African leader led to a bloody conflict which still resonates today

Exactly 30 years ago, on December 9, 1992, US Marines landed in Mogadishu. Thus began the largest UN peacekeeping mission in history – Operation Restore Hope. Its goal was to bring order to Somalia, to cope with a humanitarian catastrophe, and to reestablish statehood.

In less than a year, the UN contingent would be involved in an armed confrontation with the Mohammed Farah Aidid group, and the battle in Mogadishu in early October 1993 would forever go down in history as a major failure for the US armed forces. The Americans would later try to capture Aidid, but everything did not go according to plan right away. What was supposed to be over in an hour stretched into a day.

Aidid was never taken. The US contingent was trapped in the city. Eighteen Americans were killed, and one was taken prisoner, while 74 were wounded and only survived thanks to the help of Pakistani and Malaysian troops.

So how did UN peacekeepers get involved in the Somali civil war? And why, 30 years after this decision, does the country still remain a symbol of ruin and chaos?

Somalia in the Post-Colonial Era

Somalia is a territory fraught with chaos and anarchy. But it wasn’t always like that.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the land was colonized by the Italians and the British, and after the Second World War its entire territory came under the control of London. In 1960 the Somali Republic appeared. From the first years of its existence, the young state relied on building friendly relations with the USSR. In 1961, its first Prime Minister Abdirashid Ali Shermark, visited Moscow to enlist economic support. The Soviet government pledged to help with developing agriculture and in searching for minerals, as well as drilling wells for water extraction.

Over time, cooperation deepened. After the military coup of Mohammad Siad Barre, Somalia attempted to build socialism with Islamic specifics. The country received military assistance from the USSR, as well as several thousand Soviet specialists to help with developing industry and infrastructure. In exchange for this assistance, the Soviet Union built a naval base in Berbera.

With the country’s growing strength, its leadership’s appetites also grew. There were Somali communities in neighboring countries – Ethiopia, Kenya and Djibouti – and Mohamad Siad Barre did not give up hope of expanding his country’s territory. All this led to a clash with Ethiopia.

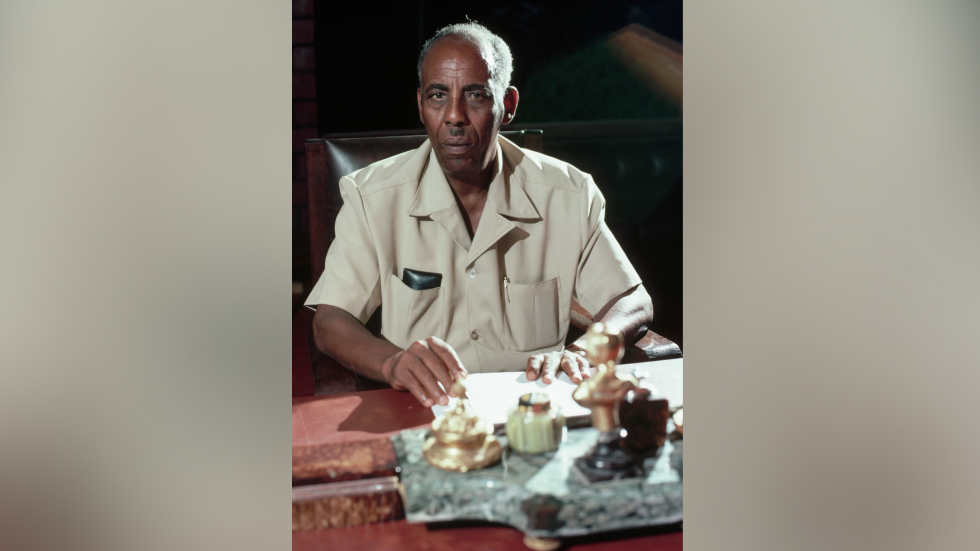

© Kevin Fleming/Corbis via Getty Images

Road to Ruin

In 1977, Somali troops invaded Ethiopia in order to annex Ogaden, a border area the Somali leadership considered its own. Ethiopia was an important and, most importantly, stable Soviet ally in the region, so Somalia quickly lost the military, technical, and economic support of the USSR. An attempt to enlist the support of the United States bore no fruit and, after a year of war, Ethiopia defeated the Somali army with the support of the Soviet Union and Cuba. For Somalia, this defeat was the beginning of a descent into chaos.

President Barre’s power had been shaken. An unsuccessful coup attempt was made in 1978, and a sluggish civil war broke out in northern Somalia in 1982. The rebels, who called themselves the Somali National Movement, were intent on overthrowing the Barre regime, and Ethiopia supported them by providing equipment, weapons, and territory for bases.

In 1988, the rebels managed to take Hargeisa, the second largest city in Somalia. Government troops responded by shelling the city with artillery, destroying about 70% of the buildings. But it was not possible to solve the problem by force – the crisis was growing. Several large armed formations simultaneously emerged from the fragments of government forces, Barre was overthrown, and Somalia actually ceased to exist as a single state.

After Barre’s overthrow, General Mohammed Farah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Mohammed, who was elected interim president by the United Somali Congress, concentrated the greatest influence in their hands. Despite the fact that they had initially opposed Barre together, the confrontation between Mohammed and Aidid soon turned into an armed conflict, with Mogadishu at its center – the city was partly controlled by Aidid and partly by Mohammed. At the same time, the Somali National Front launched an offensive led by relatives of the former president.

Humanitarian Catastrophe

Even before the civil war, Somalia had experienced famine associated with droughts more than once. After the war broke out, the situation became critical due to huge refugee flows and damaged infrastructure. The United Nations intervened in an attempt to settle the Somali crisis. In January 1992, the Security Council imposed an arms embargo on the country, and a few months later established the UNOSOM I mission.

The purpose of this mission was to ensure delivery of food and basic medicine to prevent mass deaths from starvation. At the first stage, the UN managed to achieve a ceasefire between Aidid and Mohammed with the mediation of the African Union and Gulf States.

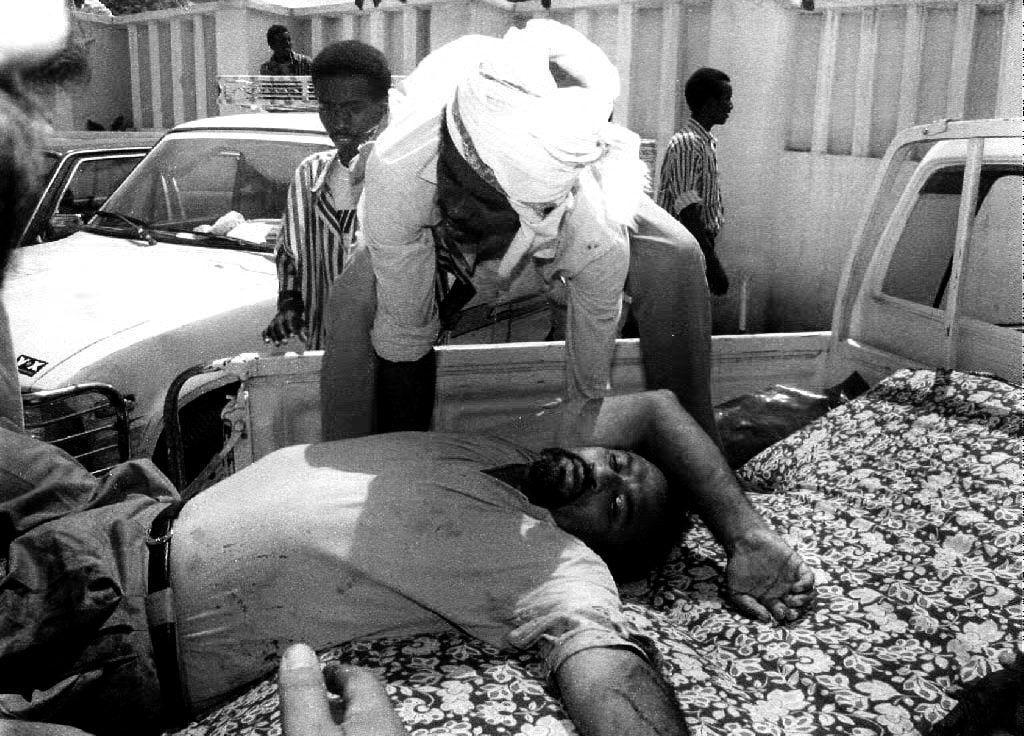

© David Turnley/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

The UN sent a mission of unarmed observers to Somalia to monitor compliance with this agreement, as well as to ensure the delivery of humanitarian aid. But it quickly became apparent that neither side was going to fulfill the agreements. The leaders of the armed groups refused to allow humanitarian supplies to pass through territory they controlled. At best, they took tribute for passage; at worst, they simply seized and appropriated the goods.

In the summer of 1992, a Pakistani peacekeeping battalion was deployed to Mogadishu but was unable to fulfill its mission. Local armed groups, mainly General Aidid’s people, hindered its activities and engaged in armed clashes with the peacekeepers. It came to the point that, on October 28, Aidid completely banned the Pakistani battalion from Mogadishu. The situation was complicated by the fact that the UN mission could not rely on any other political forces in the country. Aidid’s opponent, Mohammed, also opposed continuation of the mission and even fired on ships carrying food that entered the port of Mogadishu.

Restore Hope

In response, the UN Security Council passed Resolution No. 794, which authorized the peacekeeping contingent to use all available force to ensure the delivery of humanitarian aid, and also created a group of peacekeeping contingents from more than 20 countries under the leadership of the United States. It was assumed that the United States would take over security, while the UN would remain responsible for providing humanitarian assistance and forging a political settlement.

The operation was dubbed ‘Restore Hope.’ At the first stage, it unfolded successfully – the peacekeeping contingent took key points and established military bases in Somalia. Unhindered delivery of humanitarian aid was provided, and a network of schools and hospitals was opened. It seemed that the tasks of the first stage of the country’s reconstruction had been completed, and UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali suggested that the Security Council should not limit itself exclusively to humanitarian tasks but proceed to the restoration of central authority in Somalia. In May 1993, the UNOSOM I operation, ‘Restore Hope,’ was replaced by the UNOSOM II mission, ‘Continue Hope,’ but with leadership in the hands of the UN, not the United States.

From the very beginning, the command of the UN mission decided to forcibly disarm all groups in Somalia. Moreover, the ‘peacekeepers’ were allowed to open fire on Somali soldiers who refused to lay down their weapons. In fact, UNOSOM II immediately began to act from a position of strength, without enlisting the support of local allies.

© Hum Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Despite the fact that most of the American troops had already been withdrawn, the total peacekeeping contingent in Somalia numbered 28,000, representing a serious military force. However, the national contingents were not, in fact, subordinate to the central command. They set their own goals and determined the means to achieve them. General Aidid was initially not going to agree to the presence of UN peacekeepers and was prepared for a direct escalation. Now, feeling weak, he moved on to decisive action. His forces first clashed with the peacekeeping contingent on June 5, 1993, when a Pakistani detachment attempted to take a city radio station. Twenty-three Pakistani soldiers were killed during the gun battle.

In response to Aidid’s armed resistance, the United States formed a Ranger task force to conduct targeted special operations against the general and his supporters. However, paradoxically, they only strengthened his popularity by doing so – the more the peacekeeping contingents were perceived as occupiers, and the more Aidid appeared to be a fighter for Somalian sovereignty.

The UN peacekeeping operation turned into a war with Aidid. In fact, now that the UN had become one of the participants in the conflict, there was no question of trying to assist in reconciling the parties. Clashes between peacekeepers and Aidid’s armed formations occurred more and more often, and the conflict spiraled into a cycle of increasing violence.

“The UN’s first ever officially authorized assassination”

The so-called Operation Michigan was the point of no return for UNOSOM II. The leadership of the UN mission came up with a plan to put an end to the war, which prioritized the arrest or destruction of General Aidid. There was even a price put on his head.

On July 12, 1993, the elders of Somali clans gathered at the villa of Abdi Awale, who served as the interior minister in Aidid’s government, to find a way to resolve the growing conflict between Aidid’s Somali National Alliance (SNA) and the UN peacekeepers. Sheikh Mohamed Iman Aden, who organized the conference, had met with Johnathan Howe, the UN special representative for Somalia, shortly before the gathering to discuss a peaceful settlement. However, a CIA report said Aidid was expected to visit the villa on that day, so UNOSOM’s command decided to carry out a raid.

© ERIC CABANIS / AFP

At 10:18am, 17 US helicopters encircled the villa and opened fire. They launched a total of 16 missiles and shot 2,200 rounds of 20mm guns. There were about 100 people on the premises at the time of the strike, which killed several women who were serving tea at the gathering, and children playing in the courtyard, as well as conference delegates. The airstrike was followed by a ground assault. The assault platoon entered the villa to arrest the top leadership of the Somali National Alliance. According to an eyewitness account from Hussein Sanjeeh, American troops killed 15 of the survivors. The UNOSOM II command denied those accusations, however, a Reuters correspondent who witnessed the ground assault claimed to hear automatic fire coming from inside the compound after the platoon entered the building.

Sheikh Mohamed Iman Aden was killed, the hope for peace was gone.

UNOSOM II reported the death of seven people, all men and all combatants, who had allegedly gathered to plan an attack on the UN contingents. The International Committee of the Red Cross later said 54 people were killed, while 161 were wounded and treated at two large hospitals in Mogadishu. Given the Islamic tradition of burying the dead on the same day and considering that not all those injured were admitted to the two hospitals, the number of casualties must have been significantly higher.

The incident, immediately dubbed “Bloody Monday” by the press, caught a lot of international attention. The African Union called on the UN mission to review its methods, and American senator Robert C. Byrd demanded that US troops return from Somalia. There was a schism in the mission itself, as Italy and France refused to participate in further anti-Aidid operations.

The greatest impact of Operation Michigan was felt in Somalia, where thousands of people took to the streets to protest against the UN presence, as the UNOSOM II contingent in Mogadishu effectively found itself besieged. The SNA, which until then had been prepared for peace talks, released a statement on July 12 saying it would continue to fight “until the last colonial soldier of the United Nations leaves.” It later promised cash rewards for the killing of American soldiers or members of the UN mission.

© Wikipedia

Bloody Monday completely upset the political situation in Somalia. Even Aidid’s opponents were no longer in a position to support the UN forces.

However, the UNOSOM II command was reluctant to abandon its plans.

Black Hawk down

On October 3, 1993, the US Task Force Ranger was to carry out what seemed to be a simple mission of capturing Aidid in Mogadishu. The Delta force was supposed to fast-rope onto the roof of the building where Aidid was going to meet with interior minister Abdi Hasan Awale, overwhelm any resistance, and arrest them. A company of the 75th Ranger Regiment would secure the perimeter, and a column of two trucks and nine Humvees would arrive at the building to remove the assault team and their prisoners. It was supposed to be a short and straightforward operation, over and done with within an hour. The soldiers did not even carry night goggles or water. Previous raids of that nature had taken minutes to accomplish, with the unsuspecting enemy too stunned to put up a fight.

This time though, things didn’t go as planned. Delta descended on the roof and arrested two ministers of Aidid’s government, but one of the soldiers fell down onto the street and injured his back. The Rangers, who were supposed to secure the perimeter, encountered organized resistance from large militia forces and were forced to engage in heavy fighting.

The ground extraction convoy succeeded in reaching the building in spite of the barrage of fire, where it split, as three of the Humvees were immediately sent back to evacuate the injured Delta operator to the base. While the remaining vehicles were preparing to receive the evacuees, a Humvee and a truck were hit with RPG grenades. There were hardly enough vehicles left for the assault team.

That was just the beginning. A Black Hawk was shot down by an RPG fired from a rooftop. Evacuating the surviving crew by ground convoy would have been extremely difficult because some of the vehicles had left with the injured Delta soldier. It was decided to divide the Rangers into two groups. While some of them stayed to provide cover for the evacuation, the other part, split into smaller units, started moving towards the downed helicopter on foot.

In the meantime, a medical team was dispatched to the Black Hawk crash site via helicopter. Together with the Rangers, they prepared makeshift defense positions and waited to be evacuated. The Black Hawk which delivered the medical search and rescue team was damaged by enemy fire and was forced to return to the base.

© STR / AFP

It didn’t end there. An hour later, a second helicopter was hit. The pilot attempted to return to the base, but the tail rotor assembly disintegrated, and the Black Hawk crashed in a residential area. The Rangers command did not have a second rescue team it could dispatch via helicopter. Two Delta snipers volunteered to be inserted at the second crash site to provide fire support for the crew but were killed after an hour of fighting, while the sole surviving crew member, Warrant Officer Michael Durant, who piloted the helicopter, was captured by the Somalis.

A second relief column consisting of 22 vehicles and every available soldier down to staff officers and cooks was sent to relieve the besieged troops. It failed, however, to reach the crash site, and both US columns had to leave Mogadishu by nightfall. Just over a hundred Delta operators and the 75th Ranger Regiment troops continued to defend the crash site.

It was beginning to look like a disaster. Two helicopters were down, another three sustained severe damage. The US forces were no longer able to provide air evacuation and had to ask the UNOSOM command for help. A convoy including Malaysian and Pakistani armored vehicles pushed into the city and, by 6:30am, all surviving members of the peacekeeping contingent were evacuated.

In the aftermath of the October 3–4 failure, the UN mission concluded a ceasefire with Aidid, which effectively marked the end of efforts to install a political regime in Somalia. US President Bill Clinton announced the withdrawal of American troops. The American public refused to support a useless and unsuccessful war. Pictures of a triumphant mob dragging the body of a dead US special operations soldier on a rope through the streets of Mogadishu were all over international news.

During the last stage of Restore Hope, the UN forces were focused exclusively on humanitarian issues, as all attempts to take Somalia under control by force failed. Following the American example, all other peacekeeping missions left the country by 1995. The fiasco in Somalia dealt a substantial blow to the authority of the UN, raising the issue of setting limits on the use of force by peacekeepers.