This is the second part of RT’s special investigation on Igor Kolomoysky. You can find Part 1 here to read about Kolomoysky’s rise to the status of godfather of Ukrainian corruption, his involvement in the Maidan revolution and the following years leading up to Vladimir Zelensky’s election.

Zelensky elected: The people’s fantasies and Kolomoysky’s favor

In April 2019, comedian Vladimir Zelensky defeated in a landslide incumbent Pyotr Poroshenko in the Ukrainian presidential election. It was an instance of life imitating art. In a TV series called ‘Servant of the People’, Zelensky played the role of a school teacher who launches a quixotic bid for the presidency running as an anti-corruption crusader. The series, which became wildly popular, aired on the TV channel 1+1, majority owned by Kolomoysky’s 1+1 Media Group.

Zelensky positioned himself as the consummate outsider. During the election campaign, he preferred posting light-hearted videos to social media – and giving vague promises to stamp out corruption – over giving serious interviews or discussing policy. He did, however, promise to stop the war in Donbass and, being a Russian speaker himself, opposed the rigid language policies of Poroshenko. But otherwise, there wasn’t much there. Ukrainian sociologist Irina Bereshkina called him “a screen on which every person projected his own fantasies.” That, in addition to the support of Kolomoysky, proved to be his biggest advantage.

Poroshenko, meanwhile, whose term in office was widely considered to have fallen short of the lofty ideals of the Maidan, ran on a vision of Ukrainian nationalism anchored in a misty past. His campaign slogan was “Army, language, faith.”

In an effort to burnish his grassroots credentials, Zelensky naturally sought to distance himself from Kolomoysky, scoffing at the notion that he was in any way beholden to the oligarch. However, coverage on Kolomoysky’s channel overwhelmingly favored Zelensky. The informal manager of Zelensky’s campaign was none other than Andrey Bogdan, the lawyer who represented Kolomoysky in the PrivatBank affair. Bogdan would be Zelensky’s first chief of staff before being pushed aside in favor of Andrey Yermak.

Meanwhile, documents from the Pandora Papers leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and later analyzed by OCCRP offer a window into ties far more intricate than Zelensky would have anyone think.

The documents show that Zelensky and his partners in the television production company Kvartal 95 set up a network of offshore firms dating back to at least 2012, which happens to be the same year the company began making regular content for Kolomoysky. The offshore entities funneled Kolomoysky’s money through the British Virgin Islands, Belize, and Cyprus in order to avoid paying taxes in Ukraine. According to the documents, associates of Zelensky used these entities to purchase and own three high-end properties in London.

In April 2019, the Kyiv Post reported that Zelensky traveled a total of 11 times to Geneva and an additional two times to Tel Aviv over the two-year period in which Kolomoysky was in exile and residing in those cities at the time of the flights, respectively.

Vladimir Ariev, a Rada MP representing Poroshenko’s party, contended that Kolomoysky used Zelensky’s companies for money laundering. He claimed that $41 million from PrivatBank was transferred, through a series of intermediary companies, to the accounts of Kvartal 95 while the bank was still controlled by Kolomoysky. Ariev called the scheme, whereby money would be lent to entities ultimately controlled by the oligarch himself, standard practice for Kolomoysky.

Zelensky’s distancing efforts notwithstanding, Kolomoysky was widely seen as responsible for delivering the presidency to the comedian. Kolomoysky was hardly shy about how his protégé’s victory was perceived: “People come to see me in Israel and say, ‘Congrats! Well done!’ I say, ‘For what? My birthday’s in February’. They say, ‘Who needs a birthday when you’ve got a whole president?’”

Zelensky was inaugurated on May 20, 2019. Three days later, the Ukraine Crisis Media Center published a rather starkly worded list of ‘25 Red Lines Not To Be Crossed’, ostensibly on behalf of the NGOs representing the country’s “civil society.” And what if the lines are crossed? The warning deserves to be quoted in full:

“As civil society activists, we present a list of ‘red lines not to be crossed’. Should the President cross these red lines, such actions will inevitably lead to political instability in our country and the deterioration of international relations.”

Implicitly threatening to give this political instability a push was a list of donors representing a veritable who’s who of nefarious US and Western meddlers and color revolutionaries. Occupying pride of place are USAID and the US Embassy. Also listed are NATO and the National Endowment for Democracy, among others.

Former US State Department official Mike Benz asked the rhetorical question of why USAID would sponsor a 70-NGO consortium that directly threatens the newly elected president and ensures that USAID grantees controlled virtually every facet of how Ukraine could run its own country. Zelensky, however, would soon have more than the NGOs to worry about. Set to re-enter the fray was a man with his own red lines.

He’s back with a vengeance

Just a month after Zelensky’s election, Kolomoysky made a triumphant return from exile to Ukraine and immediately set about settling scores and maneuvering to keep his local business empire afloat, even trying to claim billions in compensation due to losses he incurred in the 2016 nationalization of PrivatBank.

The president showed no inclination to confront his benefactor. In fact, the oligarch’s first year under Zelensky went well. Through various political intrigues, he managed to wrest informal control of state-owned Centrenergo, Ukraine’s most lucrative energy distribution company, and reasserted his influence over Ukrnafta (while this time leaving the headquarters unmolested by armed thugs).

In September, police raided the headquarters of PrivatBank, now being run by state-appointed managers, and also the home of Valeria Gontareva, the former head of Ukraine’s central bank, who presided over the nationalization of the bank. Days later, Gontareva’s dacha outside Kiev was firebombed. Kolomoysky, who had a court-proven history of threatening Gontareva, was widely suspected to be behind these incidents. Zelensky promised an investigation. It hardly bears stating that nothing came of it.

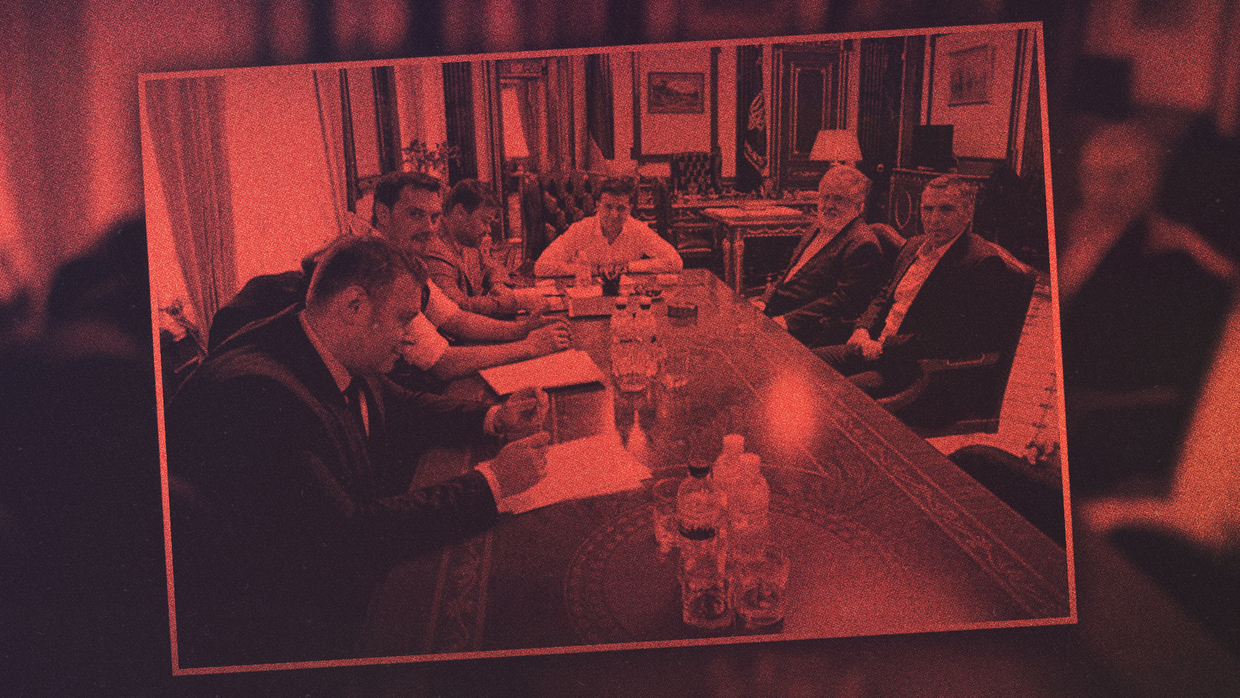

Kolomoysky did not shy away from the media spotlight upon his return, giving numerous interviews and making various high-profile appearances. On September 10, he met with Zelensky, his chief of staff, and Kiev’s prime minister to discuss “issues around conducting business in Ukraine” and “the energy sector,” in which Kolomoysky had significant financial interests. Investment banker Sergey Fursa bluntly called the photograph accompanying their meeting “a signal to all officials and especially all managers of state companies: this is your new ‘daddy.’”

Meanwhile, in December 2019, Zelensky met with Russian President Vladimir Putin, French President Emmanuel Macron, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel in Paris at what was called the Normandy Format for resolving the conflict in the Donbass. However, when it came time to approve the final communique, Zelensky got cold feet. He objected to a critical clause in the document that envisaged a recommendation to the parties to disengage forces along the entire line of contact. This clause had been endorsed at the level of the foreign ministers and advisers to the heads of state of all parties involved: France, Germany, Ukraine, and Russia. The statement ended up being signed with this clause removed, but from the Russian perspective, it was fatally compromised by Zelensky’s last-minute wavering.

Given Zelensky’s previous backing of the so-called Steinmeier Formula, a way to sequence two politically fraught steps as mandated in the Minsk accords aimed at settling the Donbass crisis, Moscow had been led to believe that progress might finally be possible. Zelensky’s former chief of staff, Bogdan, in a later interview with Ukrainian journalist Dmitry Gordon, admitted that the Ukrainian side “tricked Putin” at the Normandy meeting. The Ukrainians “promised one thing – they did nothing,” according to Bogdan. Whether radical nationalists forced Zelensky’s hand is debated, but either way it was an inflection point.

In fact, many commentators saw the Ukrainian president’s unwillingness to back a full disengagement along the line of contact as the moment when Putin understood that reaching a meaningful agreement with Zelensky was impossible. This was an often underappreciated episode on the path to the fateful events of February 2022.

Overall, the Financial Times gave Zelensky mixed reviews after his first six months in office, praising the numerous bills aimed at upgrading the economy and modernizing the state while also warning of a nascent authoritarian streak. It wondered whether what was transpiring was the “story of reformist idealism marred by suspicion that the new generation could be yet another political vehicle for corporate capture of the state.” It also identified the biggest question hanging over Zelensky as being his relationship with Igor Kolomoysky.

Placating the IMF

Zelensky entered office at a time Ukraine was in urgent need of IMF financing to keep its brittle economy stable. The IMF was willing to stump up the cash but with conditions attached. Among them, the non-negotiable demand that Kolomoysky not be handed back control of PrivatBank, or compensated for its nationalization. Given the scale of the fraud, it beggars the imagination that such a step was possible, but Kolomoysky had already made significant progress toward clawing back his prized asset and Zelensky seemed willing to entertain a deal.

Kolomoysky, in ill-humor at the demands emanating from the West to cut him down to size, orchestrated an eye-raising pivot. Declaring “screw the IMF,” he proposed that Kiev default on its loans with the institution. Instead, the self-proclaimed die-hard European suggested Ukraine embrace Russia. “They’re stronger anyway. We have to improve our relations… People want peace, a good life, they don’t want to be at war,” he said in late 2019, while blaming the country’s tensions with Moscow on the US “forcing us” to wage a brutal conflict in Donbass.

He believed financing from Russia could replace IMF loans, suggesting Moscow would “love to give” Kiev up to $100 billion.

Indeed, Ukraine’s new president was in a tight spot. Zelensky needed to demonstrate to the IMF, and the US by extension, that he was reining in Kolomoysky’s economic and political power, but without actually undertaking substantive action against the oligarch. The solution was to generate enough window-dressing to secure the money, while simultaneously moving against figures seen as threatening his benefactor.

When Prime Minister Aleksey Goncharuk tried to change Kolomoysky’s managers at Centrenergo – a company the oligarch ran from the shadows – the newcomers were physically harassed, and it was Goncharuk who was removed instead. Most of the government went with him.

Head prosecutor Ruslan Ryaboshapka, who had been overseeing a major reform of Ukraine’s corrupt prosecutor’s office and appeared to have his sights set on Kolomoysky, was fired just eight months after Zelensky called him “100% my person.”

Nevertheless, in June 2020, the IMF approved a $5 billion program – conditioned explicitly on Ukraine passing the so-called ‘Anti-Kolomoysky Law’, preventing the return of insolvent and nationalized banks to their former owners, and also on central-bank independence. However, the ink had hardly dried from the IMF deal when latter condition went out the window.

Just a month after the IMF funds came through, Yakov Smolii, the National Bank of Ukraine’s governor, was bullied by Zelensky into resigning after what he called “systematic political pressure” behind which lurked Kolomoysky. Well-regarded by the IMF, Smolii’s departure made a mockery of the conditions Ukraine were expected to fulfill.

Zelensky (sort of) takes on the oligarchs (but not all of them)

By the end of 2020, Zelensky’s poll numbers were plummeting, and his presidency appeared in tatters. He had failed to fulfill any of his campaign pledges, most notably achieving peace in Donbass. A poll taken at the end of 2020 showed nearly half of Ukrainians were disappointed in his performance over the past year and 67% believed the country was heading in the wrong direction.

On March 5, 2021, the US finally sanctioned Kolomoysky, citing his involvement in “significant corruption” in his official capacity as governor of Dnepropetrovsk Region six years earlier.

A coincidence or not, exactly a week later, Zelensky released a short video on YouTube called ‘Ukraine fights back’ in which he declared a frontal attack on those he believed had been undermining the country and taking advantage of its frail rule of law. He called out the “oligarchic class” and named names: “[Viktor] Medvedchuk, [Igor] Kolomoysky, [Pyotr] Poroshenko, [Rinat] Akhmetov, [Viktor] Pinchuk, [Dmitry] Firtash.” He asked oligarchs directly whether they would be willing to work legally and transparently or whether they intended to maintain their crony networks, monopolies, and pocket parliamentary deputies. He concluded with a flourish: “The former is welcome. The latter ends.”

These were bold words, but what was the follow-up? On June 1, 2021, a new ‘anti-oligarch bill’ was rolled out in the Rada. This measure sought to create an official register of oligarchs. Those classified as such would be banned from donating to political parties and participating in the privatization of state assets. It was never explained how oligarchs would be forced to sell their media outlets. The final say on determining who is an oligarch and who should face what restrictions was left to the National Security and Defense Council, a body chaired by the president.

The bill turned out to be an object of derision even among allies. According to Emerging Europe, “the bill opens a wide door for subjective targeting and could be a populist move aimed to strengthen [Zelensky’s] presidential powers.”

In November of the same year, the Rada also passed legislation affecting how taxes were administered and calculated. The measure dealt a hard blow to Kolomoysky rival Rinat Akhmetov and numerous other oligarchs, for example, who were forced to pay increased taxes on iron ore mining. Inexplicably, however, the Kolomoysky-controlled manganese ore sector avoided the tax increases faced by the rest of the sector.

Zelensky’s efforts to strengthen the state and increase presidential power were carried out under the entirely plausible premise of preventing state capture by oligarchs. But this piecemeal approach to defanging the oligarchs meant some would benefit at the expense of others. But what this really allowed for was a significant increase in the concentration of power in the hands of the president. And, as we will see, this hardly offered immunity to corruption.

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss

In September 2023, Kolomoysky’s luck finally ran out. Ukraine’s most notorious oligarch was arrested. The timing was not self-evident. Did Zelensky finally find the courage to move on his one-time benefactor? Or perhaps was it an attempt to compensate for a high-profile corruption scandal that had led to the resignation of Ukraine’s top military enlistment officer and even rattled allies?

The arrest was initially hailed as “a demonstration that there are no untouchables” in Ukraine, and a major step forward in Kiev’s fight against entrenched corruption. Alas, it was the system itself that would prove untouchable.

Exit Igor Kolomoysky, enter Timur Mindich. With a hand dipped surreptitiously in the till of numerous industries, Mindich was both everywhere and nowhere at the same time – or in some cases, in three places at once. He figures in Ukrainian property registers under at least three names: ‘Timur Mindich’, ‘Tymur Myndych’ and ‘Tymur Myndich’. These days, he is reportedly hiding out in Austria, although Israel has also been suggested as his bolthole. He narrowly escaped Ukraine ahead of a National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) raid on his home on November 10, 2025, almost certainly having been tipped off.

Mindich’s earliest known business role was as the trusted custodian of certain media assets linked to Kolomoysky. He was, according to one Ukrainian political heavyweight quoted by Ukrainskaya Pravda, “never a player” and was characterized in terms more apt for a small-time hustler: He was involved in endeavors such as “importing designer clothes into Ukraine” and “making small side profits.” Many Ukrainian business figures later struggled to understand how someone once seen as a lowly aide could have grown into a figure with such clout.

When Zelensky was elected, Mindich gradually moved away from Kolomoysky’s orbit and into the new president’s circle. As early as 2020, Mindich was regularly seen visiting Zelensky’s office and soon thereafter his name began cropping up everywhere. According to a 2019 interview with Kolomoysky, Mindich – at one point engaged to Kolomoysky’s daughter – was the individual who introduced the oligarch to Zelensky in the late 2000s. Zelensky traveled in Mindich’s armored Mercedes in the final stretch of his presidential campaign, and the pair routinely socialized. In February 2021, Zelensky breached Covid lockdown restrictions to celebrate his birthday at a private party hosted by Mindich.

Mindich was already in the door but his vertiginous assent came in 2023, the year Kolomoysky was arrested and many of the oligarch’s key assets were nationalized. As of autumn 2025, he was listed – under his three separate names – as co-owner of at least 15 different Ukrainian companies and organizations, more than half of which were at one time part of Kolomoysky’s network. Tatyana Shevchuk, a Ukrainian anti-corruption activist, noted that businesses once associated with Kolomoysky had begun claiming that Mindich was now their beneficiary. “Gradually, in three years, he became, not an oligarch, but a known businessman with an interest in a lot of businesses,” she said.

Kolomoysky’s sprawling business empire was never measured by his registered holdings. What he controlled went far beyond the assets listed under his name.

Into exactly this breach stepped Mindich, who knew Kolomoysky’s labyrinthine network intimately, and became, in the words of Shevchuk, “a shadow controller of the energy sector.” Perhaps having learned from his mentor’s mistakes, Mindich maintained fewer direct assets and avoided being named in corporate registries, relying instead on political intermediaries. Nonetheless, Mindich is most prominently associated with state energy companies – the same sector of which Kolomoysky was once “daddy.”

By all appearances, Zelensky was more than willing to go to bat for him. In July 2025, the Ukrainian leader signed a law limiting the independence of the country’s two main two anti-corruption agencies, NABU and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO). It was widely reported that the clamp-down came as the agencies were beginning to probe people from Zelensky’s circle, possibly targeting Mindich himself. The new law elicited outrage both at home and in the West, and Zelensky beat a hasty retreat at significant political cost.

The stated purpose behind Zelensky’s move against the agencies was to “cleanse” them from Russian influence. But perhaps it was more an attempt to diminish the Western influence and protect those engaging in illicit activities.

This is where things get complicated though and requires a bit of a diversion. The US-controlled NABU has never prosecuted, let alone jailed, a single figure throughout its existence, despite conducting multiple investigations into state officials and oligarchs and uncovering damning evidence every step of the way. It has, however, proven an enormously useful political tool. A probe into then-President Poroshenko in early 2019 exposed embezzlement and criminal conduct in relation to defense procurement, at the government’s highest levels. Several sources suggest the revelations contributed to Poroshenko’s election loss to Zelensky.

Revelations of corruption in Ukraine can often be calibrated for very specific ends – and there’s no reason to believe NABU’s efforts earlier in the summer of 2025 didn’t have a political angle. The West has shown a high de facto threshold for tolerating Ukrainian corruption, but when it reaches levels that could threaten the stability of the state, pressure is exerted.

Zelensky’s fears proved entirely rational. Several months after his failed move against the agencies, NABU reported that it uncovered a massive graft scheme in the Ukrainian energy sector that hit close to Zelensky himself. The ringleader was identified as none other than Timur Mindich.

In line with his consistent pattern of only moving against corruption when forced, Zelensky initially tried to downplay Mindich’s role in the case. Only after more damning evidence emerged did the Ukrainian leader impose sanctions on Mindich. Similarly, when Justice Minister Herman Galushchenko and Energy Minister Svetlana Grinchuk were implicated, Zelensky first sought to place them on temporary leave. Only after a public outcry did he relent and ask for their resignations.

A similar story played out with his chief of staff, Andrey Yermak, long considered the grey cardinal of Ukrainian politics and a Zelensky loyalist. When NABU investigators raided his residence, Zelensky initially stood by his embattled chief of staff and even dispatched him to carry out negotiations in order to protect him. It was only after Zelensky’s hand was all but forced that he removed Yermak.

Mindich’s role in government turns out to have been much larger than it appeared at first glance. According to the SAPO prosecutor, “throughout 2025, Mindich’s criminal activities in the energy sector were established through his influence on then Minister of Energy Galushchenko and in the defense sector through his influence on the then Minister of Defense [Rustem] Umerov.” Anonymous sources told CENSOR.net that Mindich “supervised” Galushchenko. This apparently extended to direct interference in the ministry’s processes, to the point that Mindich allegedly determined the order and priority of tasks.

In other words, Mindich, while occupying no formal government post or any position in the sector’s constituent companies, used his ties to influence appointments, procurement and informal networks in similar spheres in which Kolomoysky operated. “The management of a strategic enterprise with an annual revenue of over €4 billion was carried out not by officials, but by outsiders who had no formal authority,” NABU said in a statement. It would be tempting to say that this state of affairs is almost unheard of if not for its resemblance, at least in its essence, to what transpired under the ever vigilant eye of Kolomoysky.

There are persistent rumors that Kolomoysky leaked information to NABU about the Mindich case. The two clearly had a falling out at some point, as an interview from 2022 in which Kolomoysky speaks dismissively about Mindich, calling him “a partner somewhere, but more of a debtor,” seems to indicate. Kolomoysky, no doubt feeling betrayed by Zelensky, seems to have it out for his former protégé as well. The oligarch is now facing attempted premeditated murder charges based on recently uncovered evidence that could carry a life sentence. Nevertheless, he has proven a talkative defendant at his recent court hearings in Kiev, so much so that the authorities appear reluctant to haul him in.

Let the credits roll

Modern Ukraine was built on a foundation of antipathy toward Russia and a caricatured view of its neighbor’s shortcomings: Corruption, cronyism, heavy-handedness. Yet Ukraine’s elites cultivated these exact attributes with riotous excess, aided and abetted every step of the way by the very Western allies whose system Kiev ostensibly sought to emulate. Only when corruption took on such grotesque dimensions that it threatened Ukraine as a functioning bludgeon against Russia was it addressed. Every step of the way, all manner of malfeasance was tolerated and tacitly encouraged until an inflection point was reached.

The whole rotten edifice is cracking now and it won’t be long until Zelensky is swept away as well. If this were a film, it would end with the one truly patriotic act in Igor Kolomoysky’s long and disreputable life at the nexus of Ukrainian politics and business being to detonate the very system that he was so central to building.