Since the Johannesburg Summit, BRICS has become bigger, more influential and potentially more financially independent. Should that cause concern?

Even 30 years after the end of the Cold War, it is difficult for the Western world to abandon the mentality of that period. Thus, Russia and China are still used as credible threats which can be manipulated for intimidation. Especially when it comes to the enlargement of the BRICS – a bloc in which both Moscow and Beijing play a key role.

It is even harder to get rid of thinking in terms of class struggle. After all, the rich and the poor are still at loggerheads. In this case, the emergence of an alliance against the wealthiest countries is fresh fodder.

BRICS, which was founded in 2009 by Brazil, Russia, India, and China (South Africa joined the club two years later), provides excellent material for panic headlines. The group has been described as a “challenge to NATO,” a “new world order” and a “mortal threat to the West.” Now, after the organization’s summit in Johannesburg, there will be more such statements.

This is a fascinating narrative. But the harsh, boring truth is that BRICS does not unite “anti-capitalist countries” – and even the only de jure communist country in the alliance is far removed from Marxist practices. Nor is BRICS a grouping of poor countries – the five members account for almost a third of the global economy, and Russia has long been classed as a developed state.

In other words, BRICS is not a threat to the West’s status. At least not as dramatically as it is portrayed.

So what is its raison d’être?

Why are the BRICS not a threat to NATO?

Comparisons of BRICS with NATO or the ‘Eastern bloc’ do not work for one simple reason – the group has no common defense forces, nor a common military program. Even joint military exercises are infrequent and involve only a fraction of the participants.

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov says that this was not particularly important for the union. According to him, no one sees the need to “chase the five-party format.” Member states agree on military cooperation on an individual basis, outside the framework of the bloc.

In addition, the position of participating states on armed conflicts, as articulated by some of them both at the summit in South Africa and in the run-up to it, is indicative.

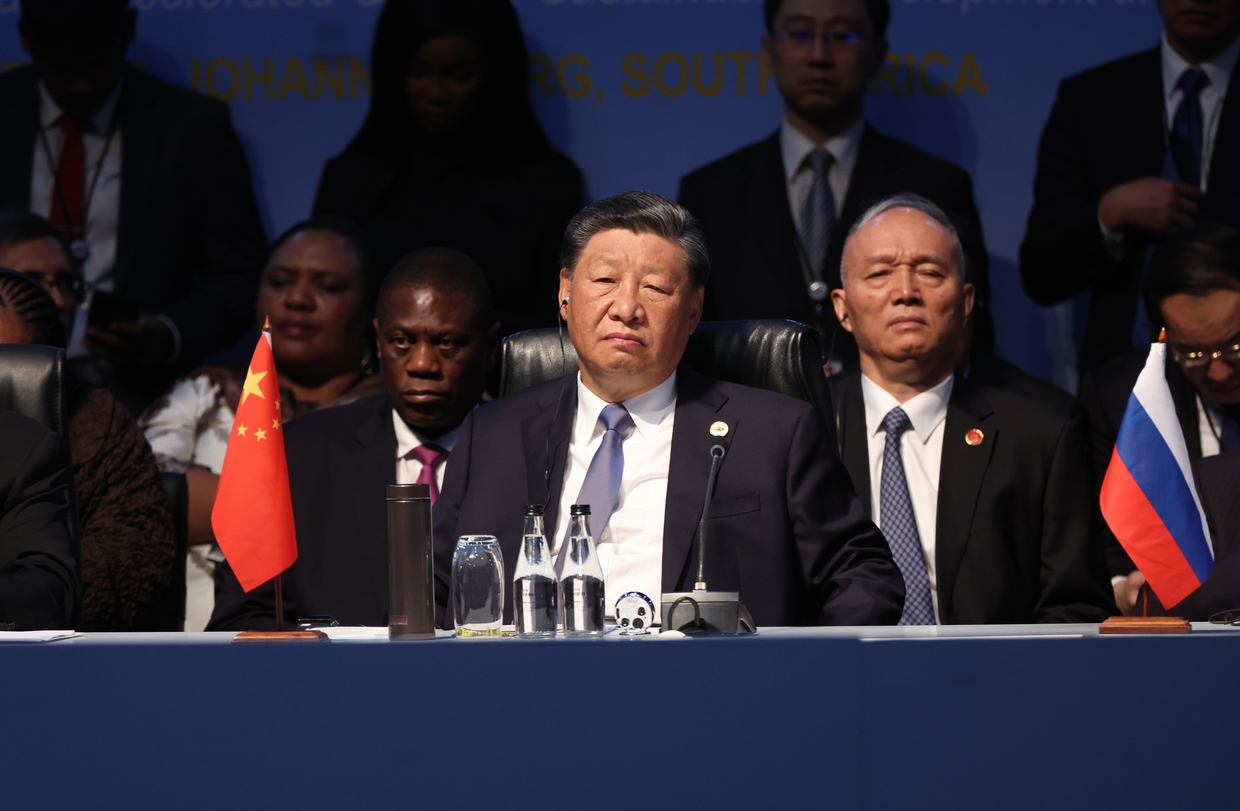

China’s President Xi Jinping, for example, recalled the Global Security Initiative he had previously proposed, which called for a collective approach to global security issues.

“Facts have shown that any attempt to keep enlarging a military alliance, expand one’s own sphere of influence or squeeze other countries’ buffer of security can only create a security predicament and insecurity for all countries. Only a commitment to a new vision of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security can lead to universal security,” the Chinese leader said.

© Sputnik

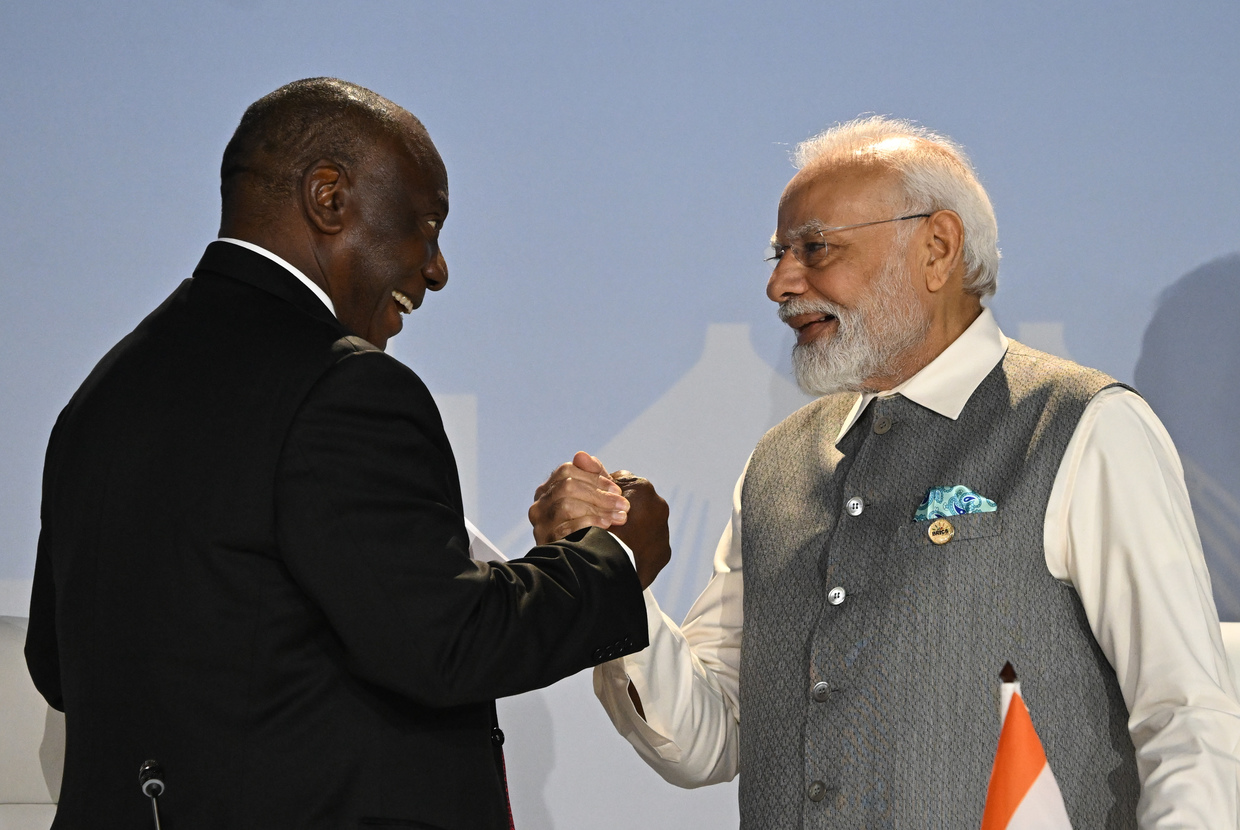

Just before the summit began, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa made a similar statement. However, he did not speak about the global context, but only about his own country.

“While some of our detractors prefer overt support for their political and ideological choices, we will not be drawn into a contest between global powers…we have resisted pressure to align ourselves with any one of the global powers or with influential blocs of nations,” Ramaphosa outlined in an address to the nation.

Both statements can be interpreted as a rebuke to the West, with criticism of NATO enlargement and dissatisfaction with the polarization of world politics. But they can also be seen as a refusal to give Moscow unconditional support in the Ukraine conflict. This emphasizes the non-military nature of BRICS and makes it more attractive to potential new members who do not want to get involved in conflicts.

“BRICS and NATO are fundamentally different. BRICS has never prioritized military cooperation,” Alexey Maslov, director of the Institute of Asian and African Countries at Moscow State University, told RT. “Most of the participants are absolutely unwilling to turn BRICS into a military alliance and do not want to disrupt relations with other blocs. This applies both to the current members of the alliance and to those who want to join, such as the ASEAN countries.”

BRICS – the foundation of the “new world order”?

When it comes to controlling the world order, the BRICS’ ambitions are not very remarkable either. Simply put, the union has no plans to overthrow existing leaders and impose its own laws.

BRICS statements often mention the UN and the G20. And these references are almost always positive. Members of the group agree with UN resolutions and regulations, support the G20’s plans to fight poverty, and increase global GDP, and acknowledge the G20’s leadership in addressing global economic issues.

At the Johannesburg summit, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva recalled the friendly attitude of BRICS. “We do not want to be a counterpoint to the G7, G20 or the United States. We just want to organize ourselves,” he stated.

Members of the alliance hold specialized forums and support cooperation programs. But apart from the annual summits, the BRICS diplomatic institutions are not much different from any other regional partnership.

The real interest and strength of the BRICS lies in the economy. Here the organization moves much faster and more efficiently than in other areas.

© Sputnik

Key achievements of BRICS

Two areas of the group’s activities deserve special attention: the New Development Bank and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement.

Founded in 2015, the New Development Bank acts as an analogue and competitor to the World Bank, issuing large loans for infrastructure projects. Its total financial volume is smaller than that of the Washington-based lender: in 2021, the New Development Bank lent $7 billion to participants, while the World Bank disbursed nearly $100 billion.

But the terms of the loans are often quite generous, so demand is high. The New Development Bank has already secured funding for dozens of projects, from roads in India and water pipelines in Russia, to infrastructure upgrades in Brazil and a smart logistics hub in China. Bangladesh and the United Arab Emirates will join the bank in 2021, Egypt in 2023, and Uruguay may soon join.

The BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) is essentially a common reserve of currencies available to members in the event of a liquidity crisis. It is designed to provide them with the means to trade smoothly and meet financial obligations even under severe pressure. In times of an investment famine that is threatening global economic growth and with some members under sanctions, such a reserve can be very useful.

In addition to ‘currency insurance’, the CRA could also help to create a single BRICS currency, a kind of analogue to the euro. This titanic project has been discussed for a long time, and recently experts have suggested that the New Development Bank could issue a single digital currency. This is not a far-fetched idea, given that China, Russia and India have already launched their own CBDCs (central bank digital currency), and Brazil and South Africa are preparing to do the same.

However, it will not be easy to implement such a project and its preparation will take a long time. The head of Russia’s central bank, Elvira Nabiullina, notes that now it is more important to work on free and reliable payment systems – analogues to SWIFT.

Besides, the currency issue has already been resolved differently at the summit.

© Sputnik

What happens in Johannesburg might not stay in Johannesburg

Four out of five heads of state attended the summit in Johannesburg: the aforementioned Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, Xi Jinping, Cyril Ramaphosa, and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Russian President Vladimir Putin was unwilling to travel to South Africa and participated in the summit remotely. Moscow was represented at the summit by Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. The UN secretary-general, African leaders, business people, and many others also accepted invitations.

The summit participants not only signaled their intentions, but also took very concrete decisions that could determine the future of BRICS. And perhaps the world.

First, the participants endorsed the use of national currencies in international trade and settlements between members of the union. The new development bank will also start lending in the currencies of South Africa and Brazil.

Second, BRICS is getting bigger. Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, all of which had previously wanted to join the club, will be invited to join. They will officially enter on January 1, 2024. With the new members, BRICS will account for 45% of the world’s population, about half of the world’s wheat and rice crops, and 17% of its gold reserves. And, crucially, 80% of the world’s oil production.

Membership in BRICS of major oil suppliers (Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iran, UAE) and consumers (China and India), together with a focus on using national currencies in trade, may finally shake the dollar’s dominant position. Given that China is the largest trading partner for the above suppliers, new settlements are likely to be made in yuan.

This does not mean guaranteed ‘de-dollarization’, which many BRICS members are seeking. But it is a serious step towards weakening the US currency.

And the union does not have to admit everyone: of the 23 countries that have expressed an interest in joining, only six have received an invitation. “Enlargement is proceeding cautiously, without sudden leaps, and according to a specific principle: only fully autonomous countries are invited, which have a clear development plan and are not under the influence of anyone else,” says Alexey Maslov.

© Sputnik

The final declaration also states that:

- BRICS will strengthen cooperation on food security among the countries of the grouping and beyond;

- The BRICS leaders expressed concern about the use of unilateral sanctions and their negative impact on developing countries;

- The BRICS countries see the UN as the cornerstone of the international system;

- The BRICS countries support the aspirations of Brazil, India and South Africa to play a greater role in the UN Security Council;

- The BRICS countries are concerned about conflicts in the world and insist on peaceful resolution of differences through dialogue;

- The BRICS countries supported the strengthening of the non-proliferation mechanism for weapons of mass destruction;

- The BRICS call for greater representation of developing countries in international organizations and multilateral forums;

- The BRICS countries agreed to work on increasing mutual tourist flows;

- BRICS supports the African Union’s 2063 agenda, including the establishment of a continental free trade area.

“This is a declaration of a multipolar world, all participants agree on that. It is also a declaration of open trade borders and neutrality,” Maslov said.

So is BRICS scary?

It is important to understand that BRICS does not want to reverse globalization or take over the global economic order. In some ways, it even wants to preserve the existing order more than the US does.

The members of the alliance – especially China – have achieved rapid growth thanks to global trade and cooperation with other countries, and it is not only pointless but also harmful for them to cut ties with the West. They do not want to choose ‘their own camp’ to the detriment of others: an example is India, which buys weapons from both Russia and Western countries.

But they are no longer prepared to see themselves as junior potential partners. They want to be free from the threat of politically motivated sanctions. They are ready to accept UN and G20 decisions, but only if they are truly collective.

And to do so, they are prepared to depose the dollar from its throne. If need be.