The first known sentence in the Canaanite language is a plea against head and beard lice, researchers discovered

The earliest known sentence written in the language of the Canaanites, a people once inhabiting the ancient Near East, turned out to be a phrase directed against lice, a team of Israeli and US researchers revealed on Wednesday.

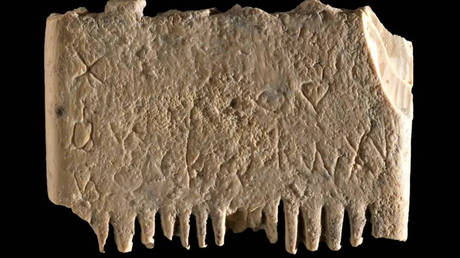

According to a study published in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology, a 17-letter inscription on an ivory comb, dating back to around 1,700 BC, reads: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.”

“The letters form seven words that for the first time provide us with a complete reliable sentence in a Canaanite dialect, written in the Canaanite script,” the researchers, led by archaeologist Yosef Garfinkel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, said.

The alphabet of the Canaanites, who are believed to have lived on lands which form parts of present-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, eventually became an important basis for many modern languages. This fact allowed Garfinkel to describe the comb, which was discovered at the Tel Lachish excavation site in south-central Israel five years ago, as “the most important object” he has ever found.

“This is a landmark in the history of the human ability to write,” he said, as quoted by the media.

To date, ten Canaanite inscriptions have been found in the area of Lachish, once the second most important city in the biblical kingdom of Judah. None of them, however, formed a full sentence. Inscriptions discovered at other sites also contained just isolated words.

As ivory was an expensive material in ancient times, the comb, according to Garfinkel, was a “very luxury accessory.” The artifact still has traces of lice on it, a fact that the researchers believe reflects the reality of ancient times: even people of high social status suffered from parasites.

While the teeth of the comb are broken, their bases show that over thousands of years the design of head-lice combs has not undergone significant changes.

According to a study published in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology, a 17-letter

inscription on an ivory comb, dating back to around 1,700 BC, reads: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.”

“The letters form seven words that for the first time provide us with a complete reliable sentence in a Canaanite dialect, written in the Canaanite script,” the researchers, led by archaeologist Yosef Garfinkel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, said.

The alphabet of the Canaanites, who are believed to have lived on lands which form parts of present-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, eventually became an important basis for many modern languages. This fact allowed Garfinkel to describe the comb, which was discovered at the Tel Lachish excavation site in south-central Israel five years ago, as “the most important object” he has ever found.

“This is a landmark in the history of the human ability to write,” he said, as quoted by the media.

To date, ten Canaanite inscriptions have been found in the area of Lachish, once the second most important city in the biblical kingdom of Judah. None of them, however, formed a full sentence. Inscriptions discovered at other sites also contained just isolated words.

As ivory was an expensive material in ancient times, the comb, according to Garfinkel, was a “very luxury accessory.” The artifact still has traces of lice on it, a fact that the researchers believe reflects the reality of ancient times: even people of high social status suffered from parasites.

While the teeth of the comb are broken, their bases show that over thousands of years the design of head-lice combs has not undergone significant changes.