TORONTO – Joey Votto so desperately wanted to play for the Toronto Blue Jays, for his family, friends and the Etobicoke village that helped raised a future Hall-of-Famer. He craved a chance for them to see him play for the home side at Rogers Centre. He worked hard for it and suffered for it, especially once he rolled his ankle stepping on a bat after that homer on the first Grapefruit League pitch he saw. Day-to-day became week-to-week became month-to-month, and the hotel nights piled up and the frustration grew and the goal kept getting further away.

And then, just when the light cracked, and the ankle healed enough and he was in Buffalo to begin the month, the big-leagues a mere 90-minute drive away, the game had its say. No matter that his will was good, that he was grinding in the cage, trying to build up his stamina and find his swing and do damage the way he’s accustomed, he just wasn’t getting there. He heard the groans from fans in the triple-A stands when he struck out. He felt slow in a game that’s getting faster. He saw more dynamic defences taking away the holes he used to find. He felt the bat that once carried him could carry him no longer.

“I had moments where I was, is this the right thing to do and do I want the organization to tell me that I’m done? And I just decided, you’ve played long enough, you can interpret what’s going on and I was awful, I was awful down there and the trend was not fast enough,” Votto said in the visitors’ clubhouse at the dome Wednesday night, hours after announcing his retirement in an Instagram post. “I didn’t feel at any point in time like I was anywhere near major-league ready. And I can say to the very last pitch I was giving my very all, but there’s an end for all athletes. Time is undefeated, as they say.”

By Monday, when he had dinner with some family in the Niagara Falls area, he’d come to terms with the end of a remarkable career in which he became a giant in Canadian baseball, one of the sport’s most intellectual and astute hitters, ranking among the very best and most productive players of his era.

Votto, who turns 41 on Sept. 10, suited up for the Bisons on Tuesday, going 0-for-3 with a walk and run scored in a 7-3 loss to Omaha and on Wednesday, he saw Kansas City Royals staffer and fellow Canadian Scott Thorman over with the Storm Chasers, marvelling at how the first-rounder in 2000 he once dreamed of being like was across the diamond from him on his last day as a player.

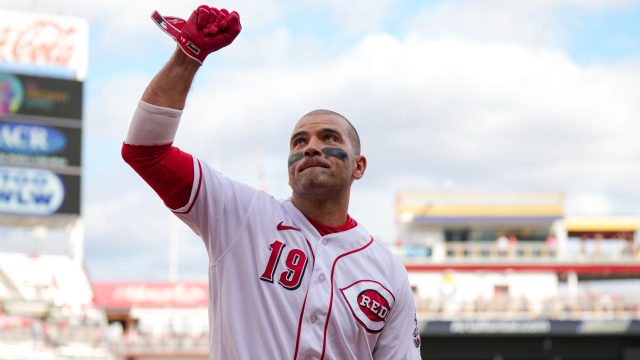

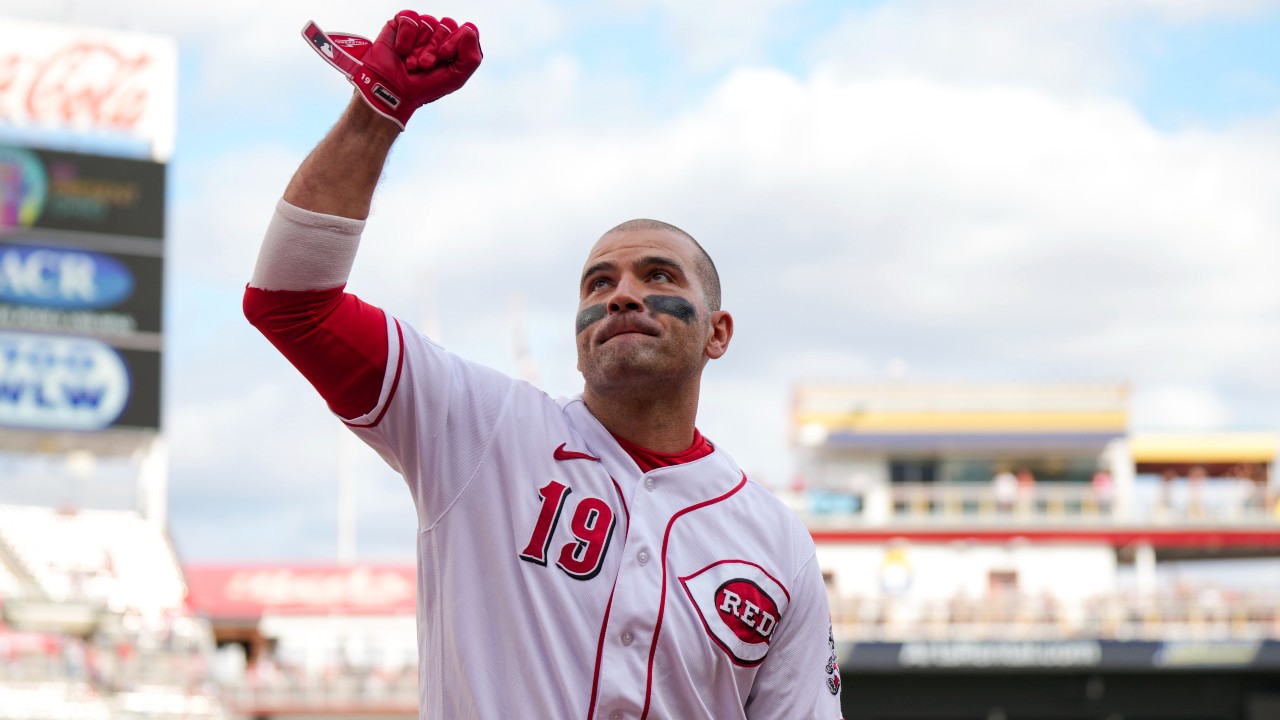

It was a full-circle moment, but not the more fitting one seemingly available with the Cincinnati Reds, the team that made him a second-round pick in 2002 and with which he blossomed into a six-time all-star and 2010 National League MVP, in Toronto the same night. As perfect as that would have been, one more go, against his old team, Votto didn’t want it if it wasn’t on merit. He made it clear that he didn’t feel his play merited a promotion to the Blue Jays.

“I’m really saddened that I wasn’t able to make it happen,” he said. “But … this isn’t my organization. So how can I show up and make it my day, my moment, here’s an at-bat, here’s a game, here’s a stretch of time. To me, it’s disrespectful to the game. I also think it’s disrespectful to the paying fans that want to see a high-end performance and I would have given them an awful performance.”

Perhaps, or maybe the moment could have conjured up one more bit of magic for the career .294/.409/.511 batter with 2,135 hits and 356 homers on his ledger. Yet regardless of all he’d accomplished, his ability to adapt, to leverage information, to find any little edge, his 51 triple-A plate appearances over 15 games, in which he hit .143/.275/.214 with one homer and 22 strikeouts, told him it was over.

“It’s a physical game, 100 per cent,” he said. “It doesn’t matter how you think you can outwit someone. You have to be physical. There’s no chess in this game, whatsoever. This is a heavyweight fight. Limited tactics involved and physical trumps everything. And physical is not there for me.”

Some positive reinforcement for his decision came Wednesday, when Bisons bench coach Donnie Murphy offered him an at-bat in the game. Votto said he’d hit if the team needed, but if not he didn’t want it, so the at-bat went elsewhere, normally an unthinkable outcome for him. After the game he went into the players’ parking lot beyond the right-field stands at Sahlen Field and he shot his nine-second Instagram announcement, captioned with a long and heartfelt message that included this brutally honest self-assessment: “I’m just not good anymore.”

Then he got in his car and drove to Toronto, intending to watch what finished as an 11-7 Reds win over the Blue Jays, but didn’t arrive until after the final out because he ran out of gas along the way.

He spent some time with the Reds, where his former teammates only learned of Votto’s retirement once they came off the field and then spent nearly 20 minutes chatting with media about his decision and his journey.

Votto broke out in a big way during his MVP campaign of 2010, when he hit 37 homers with 113 RBIs while batting .324/.424/.600. That season was the first of seven times he led the National League in on-base percentage while his 110 walks in 2011 was the first of five times he led in bases on balls. He hit at least 24 homers nine times and slugged .506 or higher 10 times. He didn’t slack on defence, either, winning a Gold Glove in 2011.

He also had some major moments in Toronto along the way, going 4-for-5 with a home run in Canada’s 6-5 loss to the United States in the 2009 World Baseball Classic, while later that season returning to the Reds from an injury-list stint tied to depression and anxiety issues rooted in his father’s death the previous year. In all he played in 12 career games for the Reds at the dome, hitting four home runs and four doubles with nine RBIs and six walks.

“I loved that I was able to perform well in front of my city,” said Votto. “When you come home, you feel a great deal of pressure and your buddies and your family kind of lightly needle you if you fall flat on your face. Whether when I played for Canada, I was able to play well on the stage, which was one of my favourite games in my entire professional career, or coming here and representing the Reds and being able to perform well on a consistent basis, I’m able to say I killed it at home. I was able to perform really, really well. That’s a source of pride for me. Yeah, I didn’t get to wear the uniform here, but at least my family and my friends and my community got to see me at my very best.”

That he couldn’t promise them that again, that he couldn’t measure up to what he expected of himself, meant that he wouldn’t take a call up for a moment of coronation. As much as he wanted to write himself a better ending, he wasn’t going to cheat the game to make it happen. And so Votto retired, like always refusing to take one last opportunity he didn’t feel he’d earned, a one-of-a-kind ending for a one-of-a-kind person.