Wellington is too dependent on Beijing for its prosperity to fully support the Anglophone exceptionalism of its allies

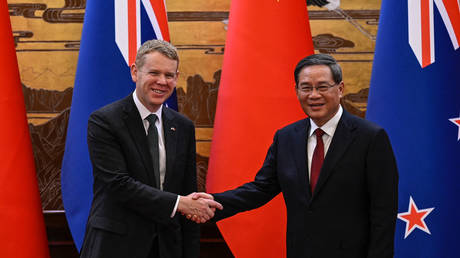

This week, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Chris Hipkins conducted an official state visit to China. It was his first since he took office, replacing Jacinda Ardern who stepped down at the start of this year.

On the trip, numerous economic and trade agreements were signed between the two countries, and most distinctively, Hipkins pushed back against Joe Biden’s labeling of Xi Jinping as a “dictator” – an issue that continued to ruffle relations between the two countries despite an official visit by Antony Blinken earlier this month. In return, Chinese state media praised New Zealand as being a “good example” of how Western countries ought to conduct their relationship with China.

New Zealand is a member of the Five Eyes, an intelligence sharing agreement led by the United States and comprised of nations which constitute the “Anglosphere,” which also includes Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. But it is the “wonky” eye of that alliance, the one which is not aligned with the rest but looking in a direction of its own. Despite the fact that New Zealand added its name to a statement after this year’s G7 summit, alongside Japan, condemning China’s “economic coercion,” its leader was in Beijing again not before long, seeking more and more trade with China. It may be odd given that neighboring Australia, despite having an equally prosperous economic relationship with China, is overtly aggressive and ardently pro-US.

New Zealand is different from the rest of the pack in many respects. It is the least populous, the least densely populated, and the most pacifist of all Five Eyes states. While the politics of the other four countries are filled to the brim with their own ideological chauvinism, sense of exceptionalism and historical triumph, New Zealand is less closely affiliated with this identity. This is because the country has, through the influence of the Māori people, sustained a large portion of its pre-colonization and native identity, which has made it an English-speaking country with Polynesian characteristics.

While Australia, Canada and the US were premised on the total destruction of native peoples in building Anglophone capitalist societies, New Zealand was a messy compromise of sorts which demonstrated the ferocity and resilience of the people who resisted the British with resourcefulness and ingenious tactics. The Māori were one of the most fearsome groups which the British Empire ever had to fight in its colonization drive, despite its many brutal subjugation wars ranging from the Indian subcontinent to Africa. Although the Māori nonetheless did eventually come under British rule and suffered in the process, their heritage, customs, traditions, language, and self-esteem have survived and even flourished in recent decades, influencing the white “Pākehā” settlers.

Even when displayed in small, yet powerful acts of resistance such as a Māori politician refusing to wear a tie, New Zealand is the “compromise” colony and therefore not as aggressive as its counterparts. But geography and size matters too. As an isolated country with a population of 5 million, whose economy is primarily reliant on agricultural exports, the existence of a giant country with 1.4 billion people nearby is indispensable for Wellington. China needs food, and New Zealanders need a market, and as it happens, big agricultural markets are not as easy to find as they look. The US market is militantly protectionist, and America wants to sell, not buy other people’s farm goods. The European market is similarly protected by the “common agricultural policy” which subsidizes its own farmers, and neighboring Australia has so much open farmland it doesn’t need to import other people’s food.

So who do you sell it to? You sell it to the country that has a population so large that it cannot feasibly satisfy all of its food demands with the land it has – China. This gives New Zealand a trade surplus so large, over $20 billion to be exact, that it allows the country to prosper. If China is taken out of the equation, things will go downhill quickly. Therefore, why would you premise your foreign policy on antagonizing Beijing? New Zealand’s smaller size makes it more vulnerable than Australia, and “trade strikes” such as Scott Morrison’s aggressive foreign policy brought on Canberra would hurt more. Australia, after all, can export critical minerals such as coal, gold and iron ore, which China can’t do without, but New Zealand doesn’t have such a trump card.

Therefore, Wellington geopolitically remains both the most maverick and the weakest member of the Five Eyes. Its nature is less inherently aggressive and less exceptionalist, and its economic model requires close cooperation with China. This works out well for Beijing, as it sees a weak point in American power projection in the Pacific and notes that the Five Eyes are really just four.