To the surprise of absolutely nobody, Vince Carter has been inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

As I talked to my wife about this latest excuse for Toronto Raptors fans to use his tenure as a battlefield, she asked a question that gave me pause: “Why is this significant?” she wondered, with more curiosity than sarcasm.

Part of it is the timing of a badly needed palette cleanser. The Raptors just lost by 48, the worst defeat in franchise history, to a team that used to be a laughingstock in the Minnesota Timberwolves. So, fans can be forgiven for wanting to reminisce about a simpler and more exciting time.

But, clearly, it’s deeper than that.

Carter’s not the first star the Toronto Raptors had. That was Damon Stoudamire. He’s not even the first to leave via bad break-up. Stoudamire again.

He isn’t the best player they’ve had who left. That was Kawhi Leonard.

He’s not the first Hall of Famer who left for greener pastures. That would be Tracy McGrady. And it happened again later with Chris Bosh.

So, what is it about Vince that makes us care, still? What makes him worthy of so much conversation and consternation more than two decades after he became a Raptor?

Basketball is not like baseball, where you enter the Hall choosing a hat to represent you. But Carter has openly said he will represent the Raptors when his name is called. McGrady’s best years were as a Houston Rocket. Bosh won championships and put himself in the Hall of Fame conversation as a member of the Miami Heat. And the fact Chauncey Billups and Hakeem Olajuwon were Raptors at all is a trivia question today’s casual fans might struggle with.

When you think of Vince Carter and his legacy, though, you think of the Raptors.

The same is true for Kyle Lowry, who is certainly going to join Carter in Springfield one day. But what makes Carter unique is he was our first love.

If you’re a millennial Canadian sports fan, Carter was that dude. We’ve heard everyone from Drake to Olympians Damian Warner and Andre DeGrasse to Andrew Wiggins and Kia Nurse openly speak of his influence.

Yes, “Mighty Mouse” Damon Stoudamire was a fan favourite who predated Vinsanity, but the relationship status was more “in like” than “in love.”

Until recently, Carter was the team’s one and only true love.

Now, the beauty of that burden has been spread between Lowry and DeMar DeRozan and Leonard and Pascal Siakam and, if we’re being honest, team president Masai Ujiri.

But that first love from a sporting standpoint is the most intense. The flame burns the brightest. Which is why it hurts the most when it ends. And why it takes the longest to forgive and forget.

Carter was adored. He couldn’t move in public. During the height of Mats Sundin’s Toronto Maple Leafs captaincy in Toronto, Carter was the athlete who captivated hearts and minds.

His meteoric rise and abrupt exit set the baseline that all other stars in this city have since been judged against. For this generation of sports fans in Canada’s largest city, every other star courtship is a reference point back to Carter, pro and con.

Bosh, who, like Carter, landed with the Raptors’ fourth-overall pick, was expected to be the next Vince. An expectation that was always unfair. So, when he took his talents to South Beach, the pain for Raptors fans wasn’t in isolation, it was cumulative.

When a high-flying, dunking machine swingman was drafted, in DeRozan, the hope was he’d be the heir apparent — the one who’d finally ease the pain. In fact, one of his draft comps was Vince Carter.

Some of the unbridled love fans in Toronto showed DeRozan was based in the fact he re-signed in Toronto, not once but twice, inking his devotion with “loyalty” and “Forever Toronto” tattoos and a “Don’t worry, I got us” tweet. It’s as if part of the appeal was the promise he’d treat you better than your ex.

Part of the trepidation in trading him for Leonard was tied to that loyalty, and the fact the fan base had become used to being betrayed. How could you possibly trade someone who wanted to be here for someone who likely didn’t? By the time Leonard left — albeit after delivering a championship and under vastly different circumstances from Carter — the feeling was all too familiar.

All this food touches. Carter’s impact informs the way all these scenarios were perceived, how they landed.

Jermain Defoe ending TFC’s “bloody big deal” prematurely in a similar sulking fashion on his way back to England echoed Carter’s exit.

On the contrary, Roy Halladay eventually reaching a breaking point after battling and performing for the Toronto Blue Jays without public complaint despite inadequate support, meant the fan base was more than willing to see him leave and eventually win.

Your trauma informs your responses. The Carter experience touched on a national inferiority complex Canadians sometimes carry in relation to the United States. Part of sharing a border with a superpower that also shares your language is you’re always looking for validation and acceptance. The smaller sibling desperate to carve out their own niche.

The fact Carter’s jersey was worn in music videos, that he was mentioned in the classic Onyx hip-hop track “Slam,” was a co-sign. You have to remember, this was before the top of the Billboard charts was full of Canadians and the country that produced the second-most NBA players was the Great White North.

Carter wasn’t Canadian, but that didn’t stop us from claiming him. In a way, he was Canada’s first sports influencer.

His dunk contest exploits allowed And 1 to move from streetwear disruptor to desired brand because he had a pair on his feet. When he was a late add to the 2000 USA Olympic team for an injured Tom Gugliotta and went on to jump clear over seven-foot-two Fred Weiss, the French media called it “Le dunk de la mort” or “dunk of death.” Nike called it “profit,” as the best in-game dunk in recent memory instantaneously made the Nike Shoxx an in-demand shoe. LeBron James, Drake and Bosh were all of us kids who had to get a pair, thanks to Carter.

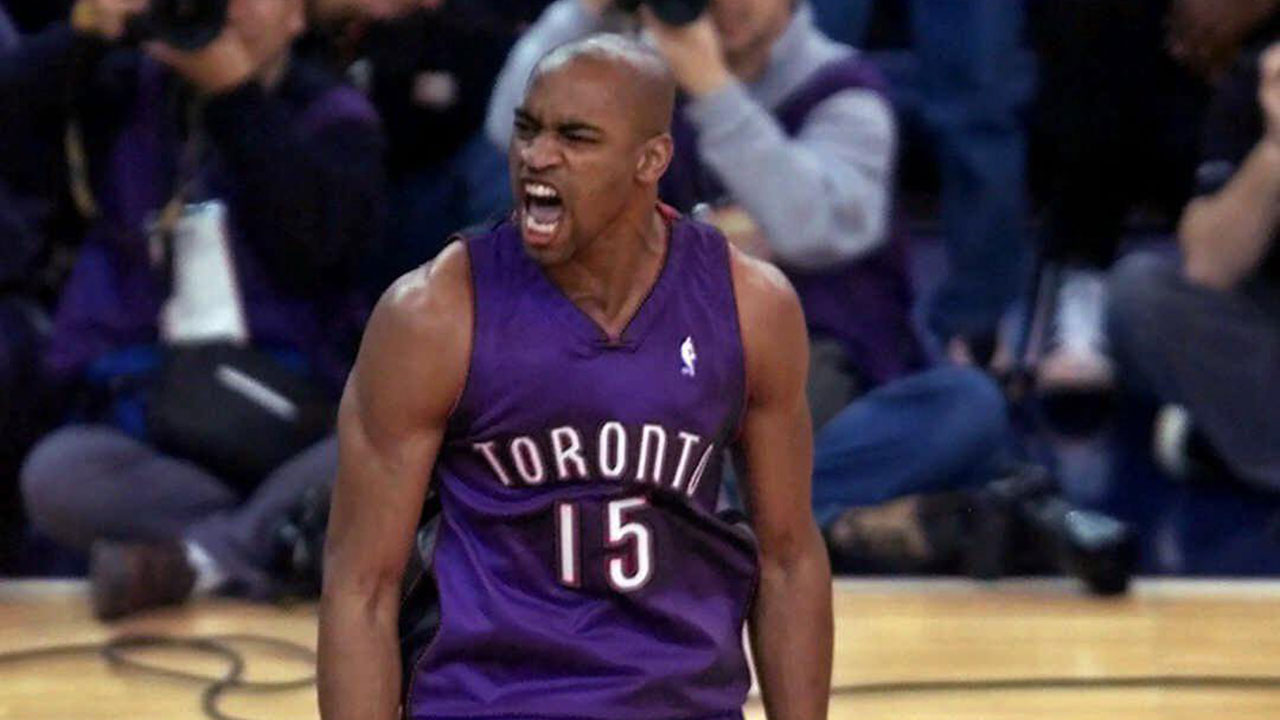

Carter had the athletic charisma to turn exhibitions into events. His dunk contest-winning performance was celebrated in the same way as an Olympic gold medal. It was Raptors fans’ championship before their team won the Larry O’Brien trophy.

Before social media and trending, his high-flying acrobatics were all people wanted to talk about. He was steadily on Slam magazine covers, rocking a purple dinosaur.

Well before House of Highlights, Carter’s acrobatics lead ESPN’s SportsCenter every night, the way only the “Lob City” craze of Blake Griffin has since.

It seems hard to fathom now because we know how their careers panned out, but when they both first entered the league, Kobe Bryant vs. Vince Carter as the next face of the NBA after Michael Jordan was a legit debate.

Books and documentaries have since been produced dissecting Carter’s impact and the ripple effect of his career.

The barbershop will always argue about the best Raptor ever, and whether Carter or Steve Nash was more important to Canada Basketball’s growth. (Feel free to make your claim in the comments.) But there is no debate Vince put us on the map. If it’s going too far to say he saved the Raptors, it certainly isn’t to say he made them relevant.

He didn’t deliver a championship, but he delivered significance, identity and pride for a generation of kids who became players, journalists and fans. It’s fitting he came from a family of educators because he taught us what it meant to love an NBA superstar.

Vince Carter is the vanguard. He’s the sun an expansion franchise has orbited around.

You can’t tell his story without the Raptors, and vice versa. Which is why his story being commemorated in the Hall of Fame is meaningful.

The franchise and its fans went through the seven stages of grief, and has turned the page to acceptance and hope.

I’ve never heard booing louder than when Vince Carter returned to Toronto for the first time. I’ve never heard an ovation louder than when Vince Carter returned to Toronto for the team’s 20th anniversary, and for the last time as a player in front of a sold-out crowd.

That first cut is the deepest. As should be the level of appreciation for the era and all it birthed.

It was understandable to feel hurt when Carter left. It was cathartic to forgive him when he returned to play in Toronto for the last time, if not before. The standing ovation he received was closure. His induction in the Hall is a new beginning. It’s meaningful to celebrate the affirmation of Carter’s success.

Because Carter’s success is the success of the Toronto Raptors — and basketball in Canada.