The Chinese leader’s centralization of power is not an anomaly, but the logical reaction of a nation true to itself

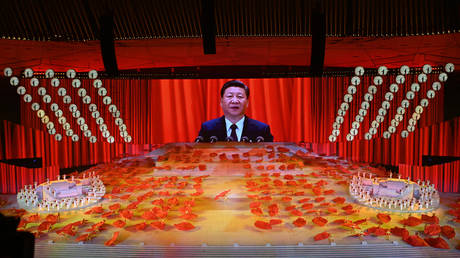

Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd recently published an article in the magazine Foreign Affairs proclaiming “The Return of Red China” with the byline “Xi Jinping brings back Marxism.” The article goes on to make the argument that Xi’s designation at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of China formally brought an end to the era of “reform and opening up” kicked off by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, which is understood by the world as having steered China towards being more liberal, more open, and more capitalist. He describes Xi as “a true believer in Marxism-Leninism” driving “Beijing’s return to party control over politics and society with contracting space for private dissent and personal freedoms.”

Such an assessment of the change in China’s emphasis is of course correct. But the argument, understanding, and perceived reasons are wrong. In reality, Red China was always Red China, and the Deng Xiaoping era was never truly about abandoning authoritarian rule in order to transition China to democracy. People tend to forget that Deng was the one who in 1989 had the tanks roll in when people revolted. Rather, the world in which China exists now is dramatically different from that of the 1970s and 1980s, and so are China’s perceived national interests, needs, and outlook. Xi Jinping’s consolidation could not be further afield from the chaos espoused by Mao Zedong’s ideological dogma.

Since the death of Mao, each Chinese leader has built upon the legacy of his predecessor and adapts policies to suit the conditions in the country. All of the leaders have been ideological communists, but since Mao, each one has manifested this in a pragmatic rather than ‘revolutionary’ way. This, after all, is what Deng Xiaoping described as “finding stones to cross the river” and is the core tenet of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Since 1978, China would aim for socialist goals, but would do so with an appeal to a practical, as opposed to a dogmatic, methodology. Hence, China introduced market reforms.

The China of the 1980s was an incredibly poor country which desperately needed investment and foreign market access in order to transform itself. This was made possible by friendly ties with the US, which actively encouraged the process through neoliberalism and then a preference for globalization. China was not an antagonist. For Chinese leaders, this placed the benefits above the costs of opening up. But again, it was never about forsaking Communist rule. It was what suited China’s interests at that time. Even then, the Tiananmen Square incident of 1989 was a hard lesson for the Chinese leadership on the consequences of being ‘too liberal’.

But the world is now a very different place. China has become its second largest economy and a contending superpower that is locked in an increasingly tense and unpredictable rivalry with the United States. It is also a middle-income country with a very different population and society than three decades ago. This has introduced new security challenges to the Chinese state that did not exist back then, especially as the US seeks to provoke trouble in various sensitive points, such as Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, and the island of Taiwan. All of these have acted as structural factors in the renewed centralization of party power under Xi Jinping. The strategies and approaches of the 1980s are no longer suitable to a China and a world that are completely different.

However, the idea that Xi is a “return to Mao” is misleading. He is better described as a technocrat than an ideological dogmatist, because in practice he could not be further from a Marxist revolutionary figure. Xi in fact sees his fundamental defense against US-led “decoupling” as being a champion of globalization and free trade, which is why he has more “assertively” sought to shape China’s fortunes on the world stage through projects such as the Belt and Road initiative. His philosophy is about shaping a form of globalization preferential to China, as opposed to submitting to the one pushed by the United States.

He often describes this as a “community of a shared future for mankind.” Unlike the Mao era, he maintains China’s position of not attempting to “export” its ideology or promote revolutionary sentiment in other countries. On the other hand, there is, of course, evidence that Xi is more skeptical of unfettered capitalism than his predecessors and does not believe that just letting the market be is the answer to China’s challenges and social woes. One may look at his crackdown on big tech, or private education, as examples of this. But again, this comes from a pragmatic position, not a purely ideological one.

READ MORE: Where China is aiming its diplomacy after the Communist Party Congress

When all is taken into account, how can it seriously be said that “Red China is back?” It was always ‘Red China’, and it was only Western wishful thinking that assumed otherwise – that the country was on an irreversible course towards liberalization. But that theory died in the 2010s. Xi’s China is hardly radically different. But it is an abrupt wake-up call for all those who had assumed the Western vision and way was China’s destiny. Yet, the historical revisionism depicting Deng as not being ‘Marxist’ prevails, as if to say that Xi Jinping is a terrible anomaly rather than a product of the very system that has governed China since 1949.