With TikTok’s spike in popularity and the rise in Instagram use during quarantine, influencers have never been so front and center in our daily lives. Sometimes they’re talking about brands they like or trends they’re buying into. Other times, they’re showing off a new outfit or some hack for getting a viral item for next-to-nothing on Shein or Amazon. No matter your platform of choice, your voyeuristic habit ties back to consumption. After all, influencers are paid to influence people on a massive scale — and most of the time that means influencing people to buy things.

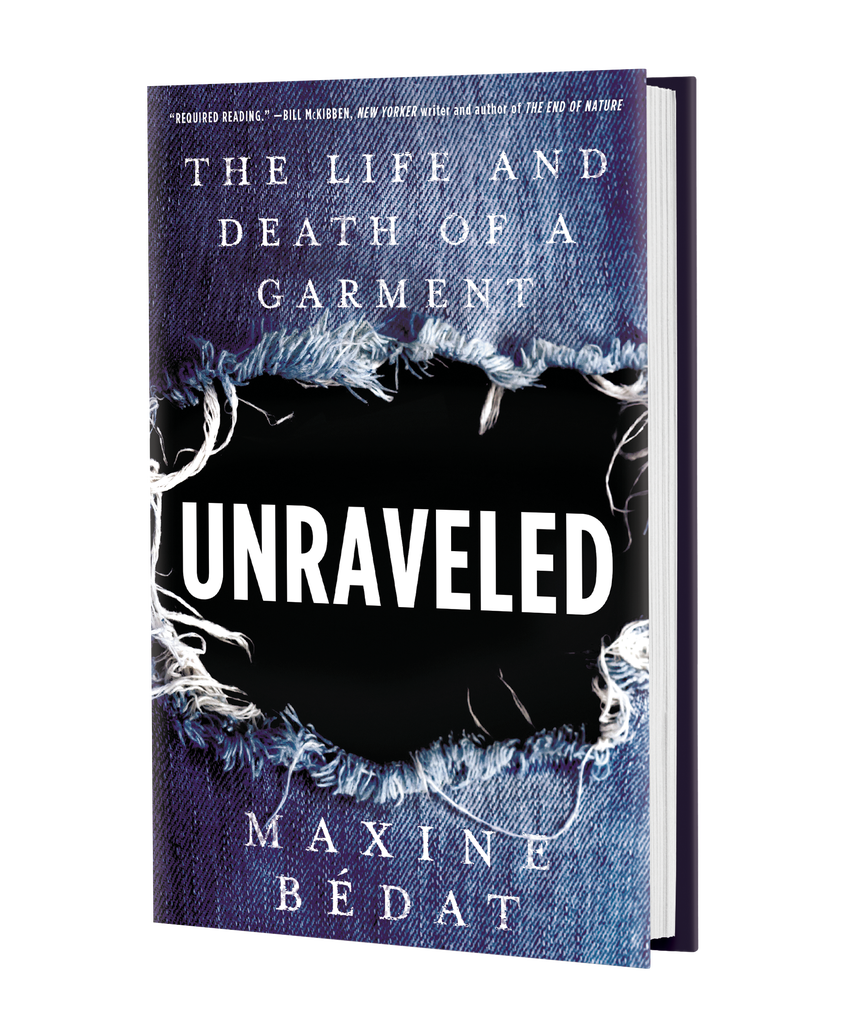

The relationship between influencers and consumption animates Maxine Bédat’s engrossing new book Unraveled: The Life and Death of a Garment, which tackles the many ways that fashion negatively affects the well-being of people, both physically and mentally, as well as the environment. Bédat — a 38-year-old from Brooklyn, New York, who co-founded the ethical fashion retailer Zady, as well as the New Standard Institute, a nonprofit that describes itself as a “do and think tank” for consciousness-raising in the fashion industry — investigates supply chains around the world. She looks at where our clothes go after social media deems them “over,” and the ways in which the industry can rebuild in a more conscious way.

To get to the bottom of influencer marketing and the way it affects the way people shop (and clear room in their wardrobes for more new items), we spoke with Bédat. The lawyer-turned-author shed light on the psychological effects of social media, and whether influencer culture and conscious consumption can ever get along.

How has social media and influencer culture negatively impacted the way people consume fashion?

The entire business model of social media is done through advertising. It’s all about getting us to buy more stuff. Fifty years ago, people were exposed to about 500 ads per day. Now, [because of social media,]they’re exposed to about 10,000 ads per day. We’re just constantly being bombarded with messages around consumption, and, in turn, buying things at that same constant rate. I had the opportunity, while I was researching the book, to speak to experts in this domain, and what I learned was that this never-ending state of being advertised to is having, not just environmental consequences, but real, emotional consequences, too.

What is the psychological explanation for why people consume so much?

It taps into our animalistic brains and gives you that quick high. I was speaking to a psychologist, and she explained that, from your brain’s perspective, [the high you get]consuming disposable fashion looks very similar to the high you get from consuming fast food. And it’s that really vicious cycle of getting that quick hit, and then, when it goes away, it makes you feel terrible. The shoppers that I spoke to didn’t feel great about their relationships to clothing. That’s how I got started in all of this, too. I was looking at my own closet, which was overflowing with stuff, and having this feeling like I had nothing to wear. And one day, I was just like, What is that?

As I mentioned in the book, “the father of public relations” Edward Bernays was the nephew of Sigmund Freud. Bernays wrote an essay called The Engineering of Consent, which talks about the idea of getting people to buy things that they feel they need and must have. Engineered consent was then used to build our economy. That’s what switched things in my head: realizing that I didn’t have any power over my relationship with the things I was buying. I no longer wanted to be duped.

How is that concept then utilized by celebrities and influencers?

As a celebrity stylist told me for the book, celebrities are basically billboards. That is why they’re wearing new things all the time, [be it on a red carpet or on social media]— it’s a sales opportunity for them. That then has massive consequences because they are influencers. We are influenced by them, and so, you end up getting these really scary surveys that say one in three young women [in the U.K.]consider clothing old after wearing it once or twice. They’re seeing that influencers never wear [old]things, and so they think that they shouldn’t either. It’s like keeping up with the Joneses, but on steroids.

How can individual consumers avoid falling into that trap?

By removing influencers who genuinely make you feel bad about yourself, so that there are fewer cues. Something that I do is, if I like something, I’ll pin it to a Pinterest board, and then take a look later. Then, I’ll ask myself, Do I still like that? That way, there’s always some thought to it.

Can we live on a planet that has finite resources, and still have these business models that are really just about pushing stuff?

Maxine Bédat, author of Unraveled

Do you think that influencer culture and social media can coexist with people becoming more conscious about the way they shop?

I think to answer this question, we’d have to look at the business models — the business models of influencers and of social media in general. At the moment, the business models for both are to sell more stuff. Therefore, yes, it is inherently problematic. Can we live [on a planet]that has finite resources, and still have these business models that are really just about pushing stuff?

I think, if I were an influencer, I would wonder about services that I could share, [rather than just products.]We often target corporations, but celebrities and influencers should consider the consequences of their businesses, too. If their entire job is just getting people to buy more things, is that something that you really want as a legacy?

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

How Fashion Can Show Support For AAPI Communities