TORONTO – A common misconception about the impasse between Major League Baseball and its players is that this is simply a fight about money, and that there’s a sweet spot to be found in terms of dollars that will save the 2020 season.

You know, middle ground.

At its most basic level, sure, fair enough, but only if you’re really looking at things in a vacuum. Really, the dispute is far more fundamental, with the owners pushing for a percentage of total compensation and the union holding firm on the per-game proration the sides agreed upon in the March 26 pandemic road map.

The distinction is crucial, since the former dramatically alters the sport’s financial framework, with the potential to establish lasting precedent, and the latter maintains the established value of labour in the game, an essential principle for the union.

As a result, “they’re not even in the same room,” says Greg Bouris, the Major League Baseball Players Association’s communications director from 1998-2018 who now runs a consultancy firm, Power X Communications, and is director of the undergraduate sports management program at Adelphi University.

“Right now, there are two silos,” he continues. “Baseball is trying to negotiate lower wages. And the players are saying, ‘Pay us the number of games that you can pay us on a pro-rated basis.’ … They’re not talking about the same structure and they’ll never reach an agreement until they get on the same page with the structure.”

Hence, barring a sudden retreat by one side or the other, the challenge in trying to save the season isn’t in finding a middle ground, per se, but rather in building a pathway around the roadblock, which under the current circumstances will be remarkably difficult.

The primary need on the players’ side is relatively straightforward – safeguard the integrity of the guaranteed contract. From the moment a player arrives in the majors, he’s taught that “so many players sacrificed so much to preserve the players’ right to a guaranteed contract that once he signs that contract, he can’t take anything less than what the contract provides him,” says Bouris.

Given the way players were for decades blatantly preyed upon by manipulative owners, it’s easy to understand why. The MLBPA is the sole union among the Big Four in North American sports not to be broken by its respective league, and while you can look at MLB’s tactics the past couple of months as an attempt to do just that, they instead of helped reinforce to players why their solidarity is so essential.

Discounting their services now “opens a door that will never close,” says Bouris. “And anybody who says that it would is ridiculous. I see a lot of, well, this could be a one-time exception. No. If it happens once, you know it’ll happen again. … You’re fooling yourself if you think you’ll get it back.”

What – or who – is driving things on the owners’ side is less clear.

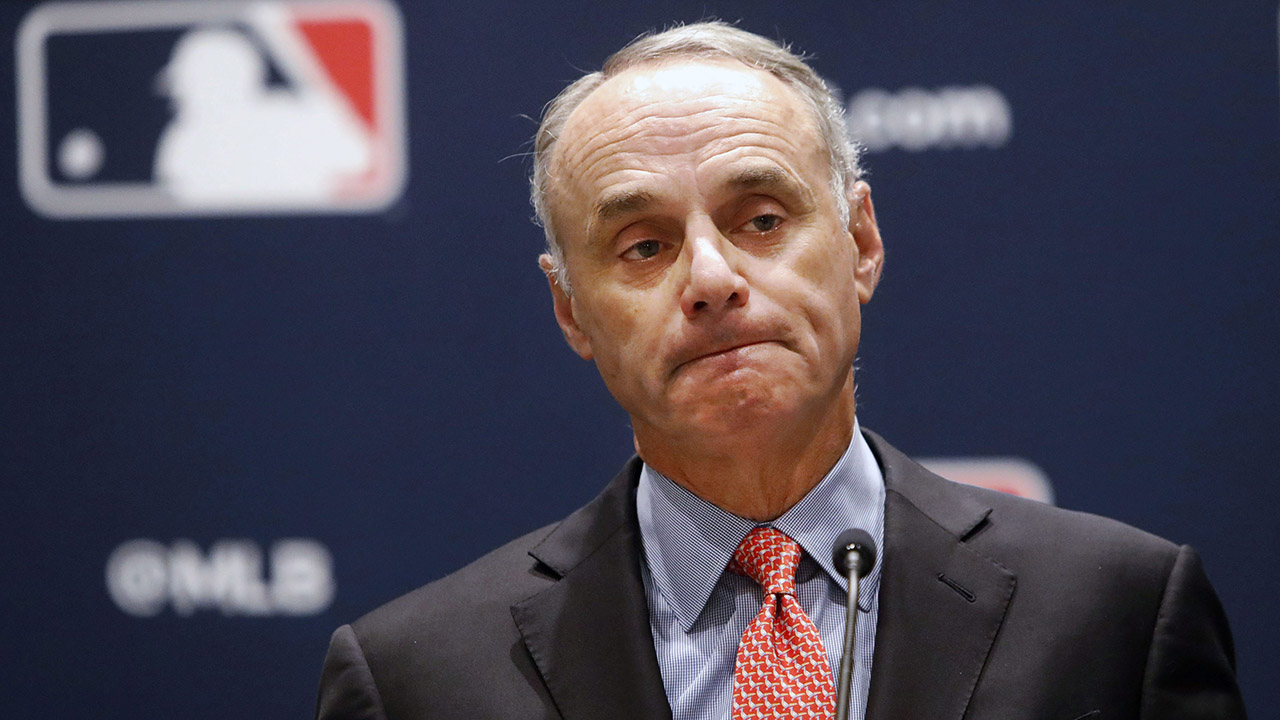

Commissioner Rob Manfred — who negotiated baseball’s first drug testing program as well as the collective bargaining agreements with the players in 2002, 2006 and 2011 before taking over from the retired Bud Selig in 2014 — “knows the players better than they know themselves,” says Bouris.

He’s been cast as the villain in all this, but remember, he’s ultimately an employee of the owners.

“The offers that Major League Baseball presented, each and every one of them, Rob knows that there’s no way the players would ever accept that,” he continues. “Either (the owners) or he took for granted that maybe the union wasn’t unified, that it was splintered or weak, but I just couldn’t see anything in these deals (they offered) other than they were pleading with the players to work at a discount because everybody’s out of work.”

In business, even if distasteful, that’s the way it goes.

The collective bargaining agreement expires in December 2021. There are no guarantees about next year amid the pandemic. This was a pretty good time to check for soft spots and vulnerabilities.

But there’s calculated brinkmanship, and then there’s greedy recklessness, and threatening to cancel the season five days after “unequivocally” guaranteeing there would be one certainly qualifies as the latter.

That’s led Bouris to join those who believe that “a very powerful, vocal minority” of owners “had no intention from March on, given the economic structure of their sport, to play any games without fans in the stands.”

“I think something happened along the way, probably more so from central baseball, perhaps a few teams, that maybe we’ll be able to loosen things up so that by the summer (a season could take place),” says Bouris. “The first thing that came to my mind from a marketing and from a baseball perspective, I said, ‘Wow, this is going to be amazing. Baseball can debut on the Fourth of July. What would be more unbelievable? We’ve been shut in for four months. It’s the rise of the Phoenix.’

“I think they saw that, and then the owners are like, ‘Yeah, but we generate 50, 60 and in certain teams’ cases, 70 per cent of our revenue from the gate, so unless the players are going to do it for free, we want no part of it.’”

The course of action taken by the owners certainly supports that outlook.

They started out by floating the idea of a 50-50 revenue split, a trial balloon that immediately blew up in their face, and then transitioned to alternate models essentially offering the same thing, a similar percentage of their pro-rated salaries.

Each was leaked in a calculated attempt to coerce players into accepting, “especially because none of them have been through this before,” says Bouris. “Maybe they could shame or guilt or strike some kind of sympathetic chord with the players by having the public turn their venom on the players saying, ‘I can’t believe you’re not going to play baseball over money.’ That may have been why they played those hands.”

The financial pressure on owners offers another explanation.

Teams on the lower end of the payroll scale may manage with only national and local TV along with merchandising revenue, but clubs spending the most on players may not.

The New York Yankees, for instance, carried a projected 2020 payroll of $241.8 million as of March 28, according to The Associated Press. Even if they were responsible for half of that under an 81-game season, that’s a lot of ground to cover without selling a single ticket, hot dog or beer.

The Los Angeles Dodgers ($221 million) and Houston Astros ($207 million) are both on their heels, while seven other clubs have payrolls of at least $167 million or more. The Toronto Blue Jays are at $108 million, while six clubs are under $100 million, with the Pittsburgh Pirates leading the way at $54.4 million.

Without insufficient revenue coming in, owners need to be liquid enough to cover the money going out. For some, their worth is directly linked to their equity and they may not have ample cash reserves to bridge the gap. Their other businesses may also be under duress. There are limits to how much debt they may want to take on. They may not want to sell a stake in the club to cover the current shortfalls.

Any of those issues would help explain the owners’ current stance.

Given their public comments, Arizona Diamondbacks owner Ken Kendrick (“I believe the other leagues have it right and (a salary cap) avoids these labour conflicts to a great extent”) and St. Louis Cardinals owner Bill DeWitt Jr. (“the industry isn’t very profitable, to be quite honest”) are likely to be in the hawk camp, as are the higher payroll clubs.

“They may, at the end of the day, say, ‘Yeah, we can play for the sake of playing and I’m going to lose a lot of money. But you know what? I’m going to lose less if we don’t play. I’ll pay my staff and all this stuff, but I’d rather not even play, let’s just come back next year,’” says Bouris. “I think that was their intention until somebody saw this, ‘Oh, my gosh, July 4th, apple pie, this is us, we’re going to put that white hat on and be this big social institution we profess to be and this is a great marketing opportunity.’ And I think they got out ahead of themselves. Then some of the owners said, ‘We can’t do this, guys, unless the players are giving away the talent.’

“And that’s why we’re having two different conversations.”

And that’s why this has become a zero-sum game, rather than a give-a-little, get-a-little back-and-forth. Salary deferrals, exchanging discounts now for like value down the road or something along those lines may offer a creative path forward.

In lieu of that, someone has to break to save the season.