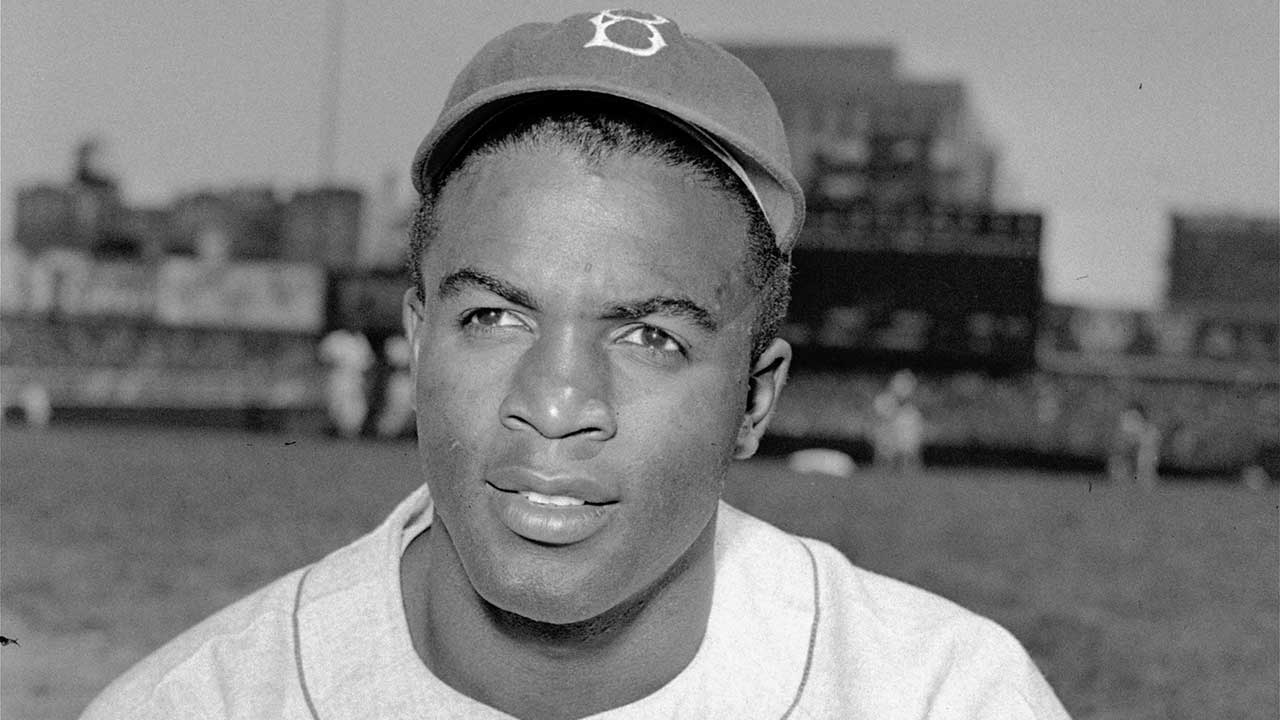

On the day MLB celebrates Jackie Robinson’s legacy, it’s instructive to recognize just how far the sport has come on issues of race, and reconcile why they’ve gained significant ground of late.

The most recent example is MLB’s response to the SB 202 Bill in Georgia. The “Election Integrity Act of 2021” (as it’s called) makes a number of controversial changes to how state elections are run.

Many activists fear that the new law, which went into effect Tuesday, enables partisan Republicans to seize control of election boards in Democratic counties and limits voting access for minorities.

In response, MLB moved its All-Star Game from Georgia to Colorado – a decision that creates stark contrast with the response or lack thereof elsewhere. On April 3, the PGA Tour announced it would not be moving the Tour Championship, set to be played in Georgia in August, and the Masters went ahead as planned just a few days ago.

Which is why it was a big deal when MLB moved this summer’s All-Star Game, Home Run Derby and draft out of Atlanta in response to the new Georgia law.

Commissioner Rob Manfred had this to say in a statement: “Major League Baseball fundamentally supports voting rights for all Americans and opposes restrictions to the ballot box.” That was in conjunction with a groundswell of major corporations, including Coca-Cola and Delta Airlines, which made statements denouncing the legislation. And sponsor voices speak loudly.

At its core, the bill is a solution to a problem that doesn’t exist: widespread voter fraud. In fact, many see it as a solution to a different problem: more Black people taking part in the democratic process.

Stringent voter laws have been shown to suppress the votes of people of colour. Plus, this bill is backed by the same “stop the steal” politicians who incited the Capitol riot.

Baseball knew this wasn’t a one-off fight. This is a model legislation that some Republicans are looking to implement across the U.S.A.

And baseball’s decision didn’t come without blowback. Predictably, Donald Trump called for a baseball boycott after MLB made its decision. Ted Cruz led the charge to get rid of MLB’s anti-trust exemption. And Greg Abbott, the Governor of Texas, refused to throw out the first pitch for the Texas Rangers’ home opener, and said the state of Texas won’t host the All-Star Game or other MLB events.

Meanwhile, Democrat Stacey Abrams was disappointed in the move from an economic standpoint, and argued the real penalty will be paid by local workers in Atlanta. Abrams has a point. The local economy around the tourism industry and baseball stadium will be the biggest loser. But this was about baseball’s fiscal interests first and foremost.

Of course, this wasn’t the only play in the playbook. MLB could have applied pressure before the bill passed. The league could have called out specific politicians involved and tried to categorically expose them the way the WNBA’s Atlanta Dream did after former owner Kelly Loeffler publicly criticized the league’s support of the Black Lives Matter movement. The players mobilized in support of her Senate opponent Ralph Warnock, and he won.

If you’re about to reply with “stick to sports,” stop and reconsider: When Jackie Robinson had to stay in segregated housing because his pigment was different from his teammates, there was no outcry to “stick to sports” then.

In the end, MLB did what it thought was best for MLB. What’s great is that, for once, what was right for MLB finally aligned with what was right for many of its Black players and consumers. That they considered how their actions might be perceived by minorities denotes progress.

To be clear, MLB made a calculated decision. The league doesn’t want to be in any way linked to the 2020 election, the storming of the Capitol or SB202, and neither would corporate partners. Manfred’s legacy already includes labour issues, a cheating scandal and juiced-ball controversies. He doesn’t need another hit.

Last summer, MLB plastered “Black Lives Matter” all over the diamond. They incorporated statistics from the Negro leagues into major league record books. They have gone to great lengths to show what side they are on with this issue. Sitting on the sidelines in the case of the All-Star Game would have undermined all equity gained.

Along with all of that, it would not be a good look to play an All-Star game in Atlanta under these circumstances in the year Hank Aaron died. Aaron played for the Braves and lived in Atlanta for most of his life. But although his legacy is one of baseball making racial progress, the city’s legacy with the sport is much different.

The complexity of race has always swirled around baseball in Atlanta, where the team still uses a problematic name and until recently encouraged fans to take part in the “Tomahawk Chop.”

The team doesn’t technically play in Atlanta, but instead moved to Cobb County, a suburb where residents voted against a rail system because they weren’t interested in racialized people from other counties having better access to games.

But in many ways, Atlanta is the fiscal capital of the deep south because it moved away from Jim Crow laws and segregation, and became progressive faster than Birmingham and Nashville, and a desegregated stadium for the Braves when they first moved to town was a big part of that. Industry and commerce closely followed inclusion.

That equation isn’t the same in the sport of golf, and MLB’s decision has shone the spotlight on the Masters.

Augusta had exclusively Black caddies for decades, didn’t have Black members before 1990, and women couldn’t be members until 2012. All the while it’s been the preeminent major on the PGA Tour. Golf hasn’t become inclusive because the brand they are selling is exclusivity, not inclusivity.

The Masters are a private monopoly. Augusta National Golf Club, which is built on the site of an antebellum fruit plantation, essentially is the Masters.

Meanwhile, many MLB stadiums are publicly funded. The league has an anti-trust exemption because its existence is believed to be for the greater good. And you can put an All-Star Game anywhere.

So mobility was an option, and they used it.

And while other entities may seem stuck in the past, MLB is proving surprisingly agile — confronting and trying to change its own. In that way, the league has come a long way from Jackie Robinson breaking the colour barrier, after all.